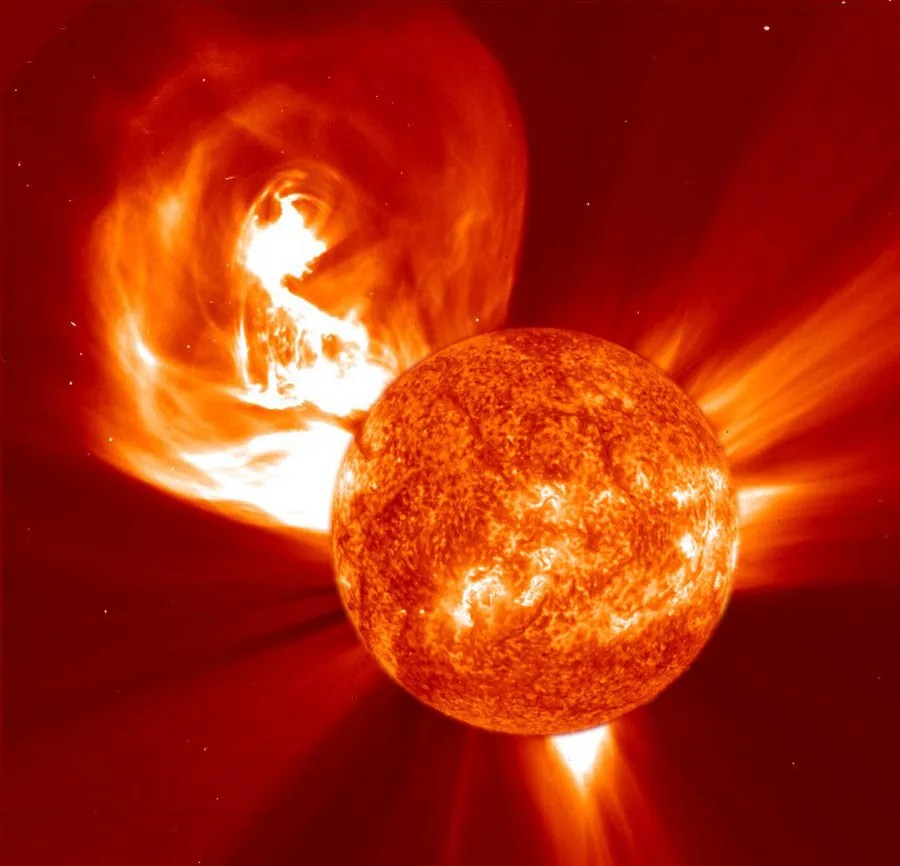

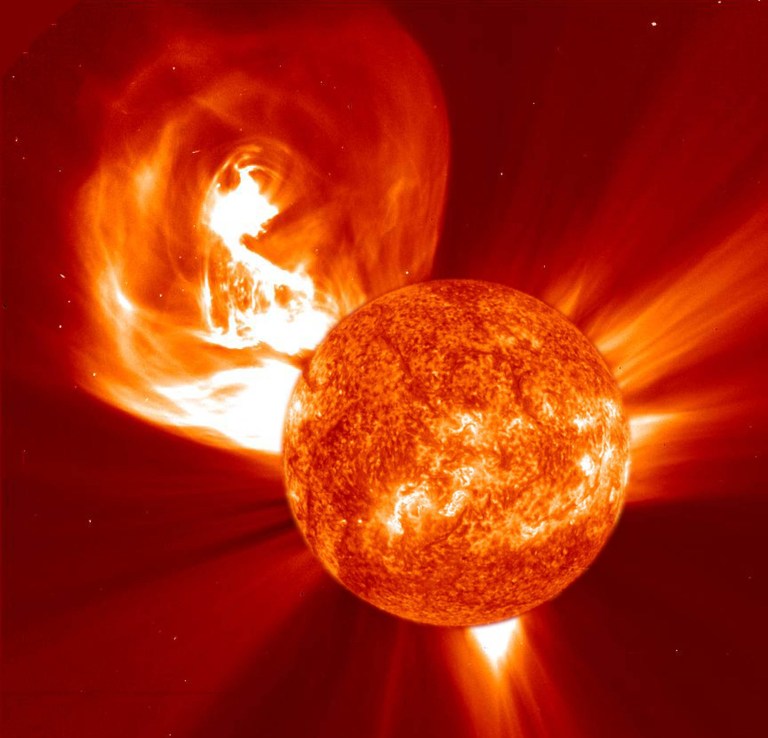

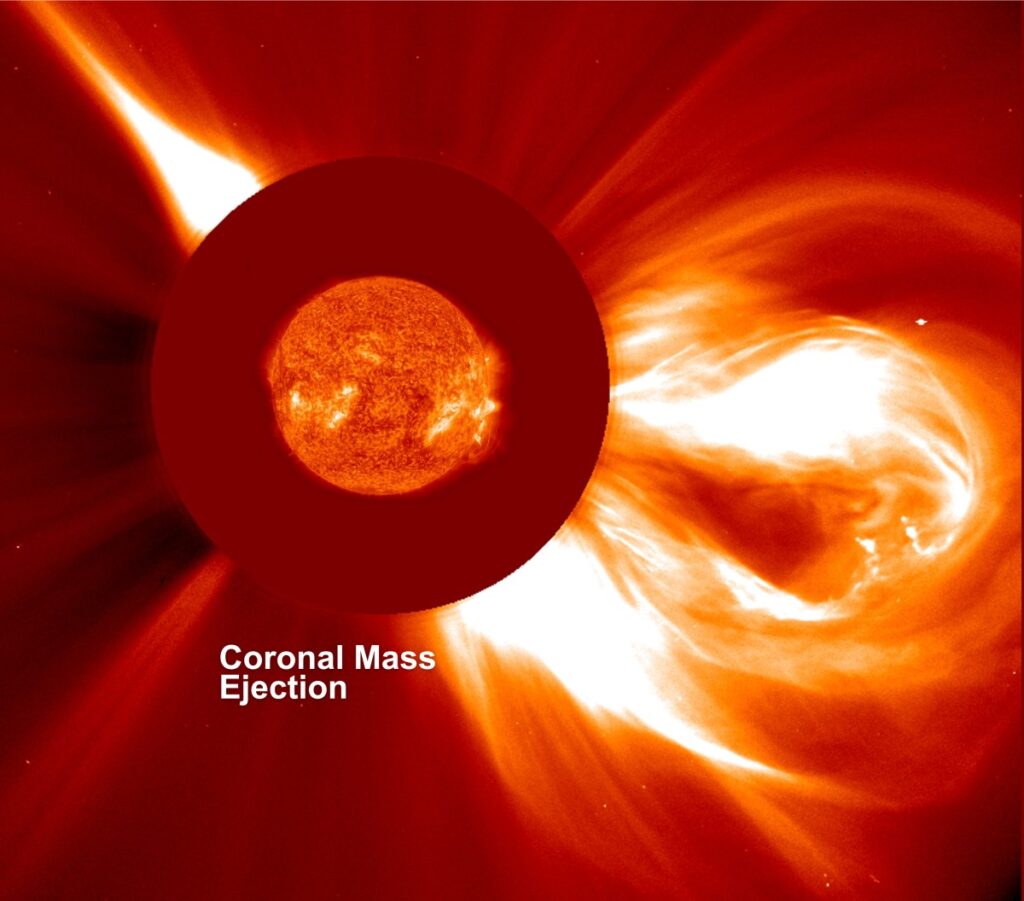

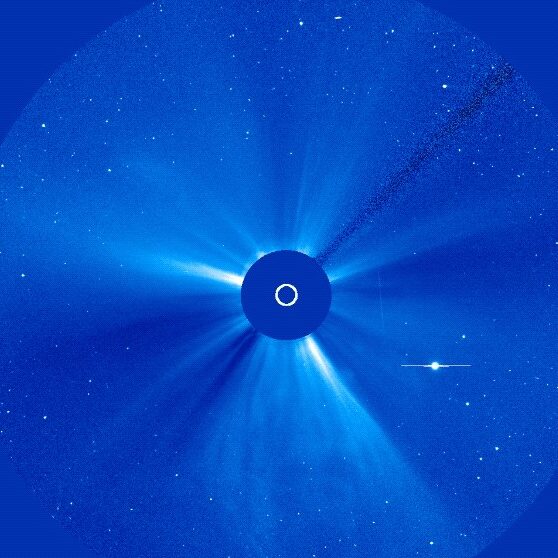

Eruptions on the Sun can affect us here on Earth In this composite image of a coronal mass ejection, a SOHO/EIT image of the Sun taken in extreme ultraviolet light at about the same time (January 4, 2002) has been enlarged and superimposed on a coronagraph image from SOHO. In coronagraph images, direct sunlight is blocked by an occulter (covered by the Sun in this composite) to reveal the surrounding faint corona.

What is a solar storm?

A solar storm is a sudden explosion of particles, energy, magnetic fields, and material blasted into the solar system by the Sun.

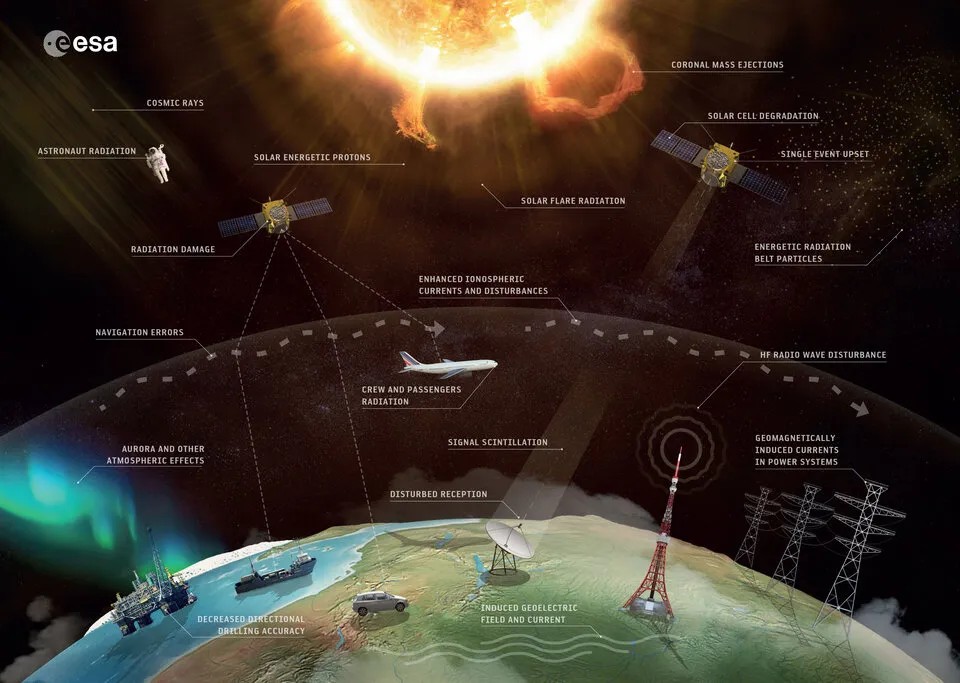

How does a solar storm affect us?

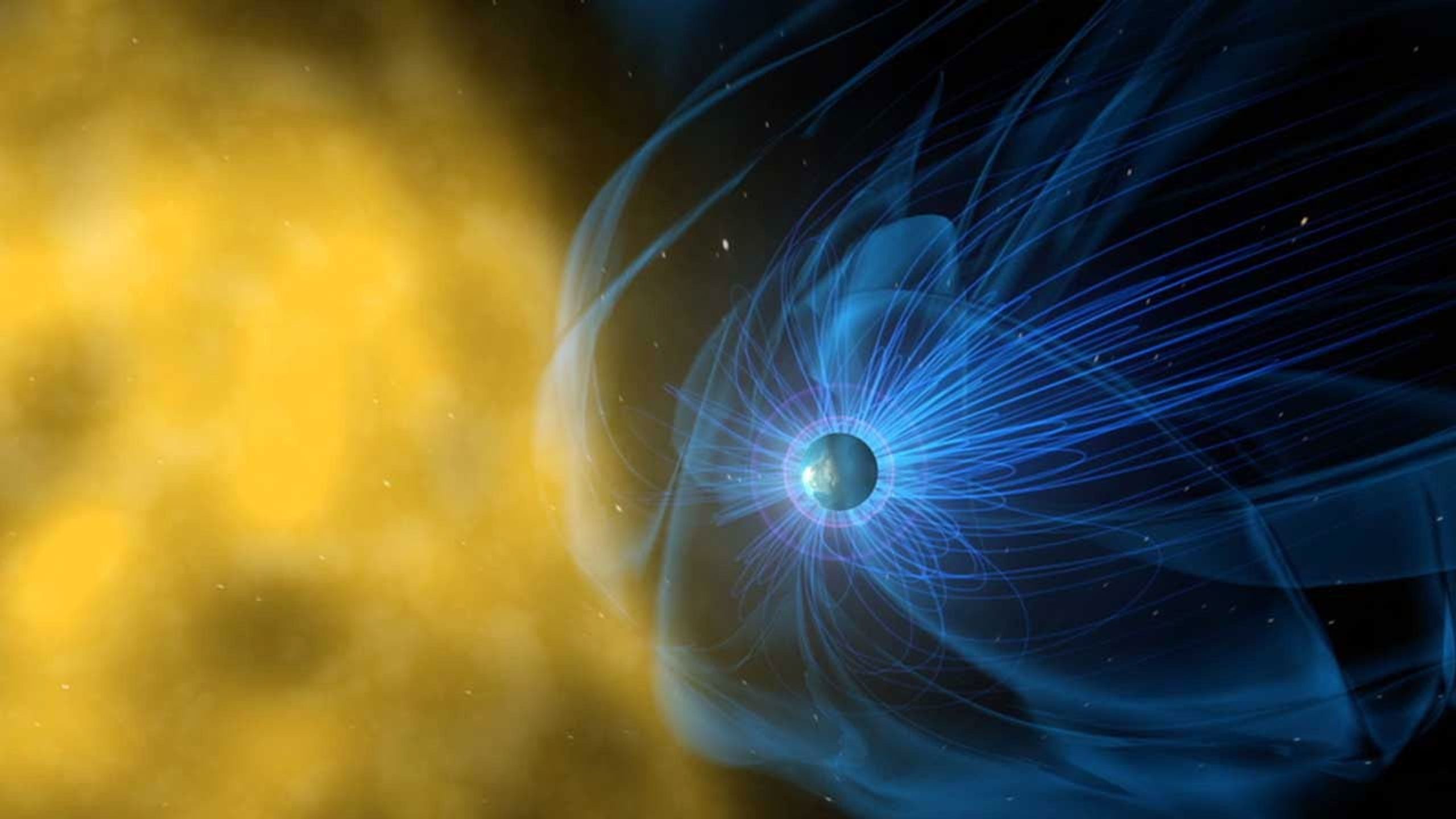

When directed toward Earth, a solar storm can create a major disturbance in Earth’s magnetic field, called a geomagnetic storm, that can produce effects such as radio blackouts, power outages, and beautiful auroras. They do not cause direct harm to anyone on Earth, however, as our planet’s magnetic field and atmosphere protect us from the worst of these storms.

What causes a solar storm?

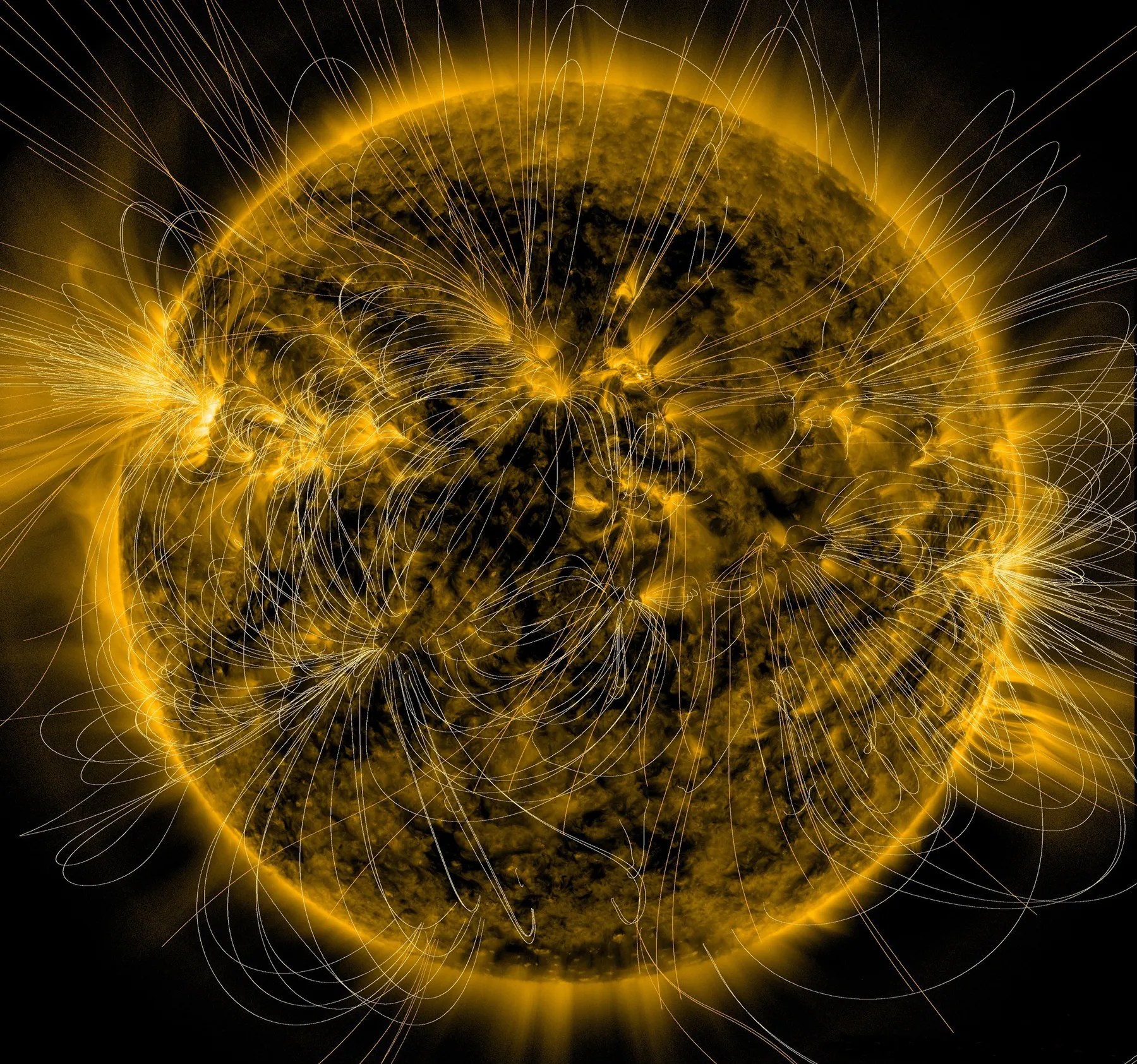

The Sun creates a tangled mess of magnetic fields — kind of like a disheveled head of hair after a fitful night of sleep. These magnetic fields get twisted up as the Sun rotates — with its equator rotating faster than its poles. Solar storms typically begin when these twisted magnetic fields on the Sun get contorted and stretched so much that they snap and reconnect (in a process called magnetic reconnection), releasing large amounts of energy.

In this composite image of a coronal mass ejection, a SOHO/EIT image of the Sun taken in extreme ultraviolet light at about the same time (January 4, 2002) has been enlarged and superimposed on a coronagraph image from SOHO. In coronagraph images, direct sunlight is blocked by an occulter (covered by the Sun in this composite) to reveal the surrounding faint corona.

A depiction of the Sun’s magnetic fields is overlaid on an image of the Sun captured in extreme ultraviolet light by NASA’s Solar Dynamics Observatory on March 12, 2016.

These powerful eruptions can generate any or all of the following:

Solar Flares

A solar flare is an intense burst of radiation, or light, on the Sun. These flashes span the electromagnetic spectrum — including X-rays, gamma rays, radio waves, and ultraviolet and visible light.

Solar flares are the most powerful explosions in the solar system — the biggest ones can have as much energy as a billion hydrogen bombs.

what is a radiation storm?

Radiation Storms

Solar eruptions can accelerate charged particles — electrons and protons — into space at incredibly high speeds, initiating a radiation storm.

The fastest particles travel so quickly they can zip across roughly 93 million miles from the Sun to Earth in about 30 minutes or less.

High-speed particles from solar eruptions can sometimes:

- get past most of Earth’s magnetic defenses, following Earth’s magnetic field lines toward the north and south poles, where they enter our atmosphere and possibly even hit the ground (but don’t harm anyone on the ground).

- knock electrons off of atoms and molecules in our atmosphere (ionizing them), altering high-frequency radio communication.

- pierce deep into satellite hardware, degrading solar panels and damaging circuits.

- pass through human tissue, posing radiation risks to astronauts in space or to crewmembers and passengers in high-flying polar aircraft.

Solar flares are classified according to their intensity, or energy output.

A – the weakest flares, barely noticeable above the Sun’s background radiation

B

C

M

X – the strongest flares

Much like the Richter scale for earthquakes, each higher class is a 10-fold increase in energy. So an X flare is 10 times stronger than an M flare and 100 times stronger than a C.

Flare classes A through M are divided further using numbers 1 through 9, with 9 being the strongest.

X-class flares can go even higher and have no upper limit. The most powerful flare ever measured was in 2003, which was recorded as an X28 before our sensors were overwhelmed.

The energy from a flare travels at the speed of light, which means it reaches Earth about 8 minutes after a flare happens. Essentially, by the time we see a flare, most of its effects are here.

Fortunately, harmful radiation from a flare does not physically affect us on the ground, as we’re shielded by Earth’s atmosphere and magnetic field. However, strong flares can disrupt radio communications that pass through the upper atmosphere, and they can affect satellites or spacecraft beyond our planet’s protection.

What is a coronal mass ejection?

Coronal Mass Ejections

A coronal mass ejection (CME) is an enormous cloud of electrically charged gas, called plasma, that erupts from the Sun. A single coronal mass ejection can blast billions of tons of material into the solar system all at once.

CMEs occur in the outer atmosphere of the Sun, called the corona, and often look like giant bubbles bursting from the Sun.

Let’s take a closer look at each of these phenomena.

CMEs can detonate in different directions and move at different speeds.

The fastest ones travel at millions of miles per hour. When directed at Earth, CMEs can reach our planet in as little as 15 hours, while the slowest ones can take several days to arrive.

As they billow away from the Sun, fast CMEs can sweep up and accelerate any charged particles ahead of them, potentially increasing the intensity or risk of a radiation storm.

CMEs carry not only charged particles but intense magnetic fields. With the right conditions, CMEs can trigger strong geomagnetic storms when they reach Earth.

When they interact with Earth’s magnetic environment, CMEs can:

- induce electrical currents that flow through power grids, potentially damaging components such as transformers, relays, and circuit breakers, leading to power outages.

- temporarily heat up Earth’s upper atmosphere, causing it to swell and increase drag on some Earth-orbiting satellites, which makes the satellites slow down and lose altitude.

- bombard Earth with charged particles that interact with atoms and molecules in Earth’s atmosphere to create the aurora borealis and australis (northern and southern lights).

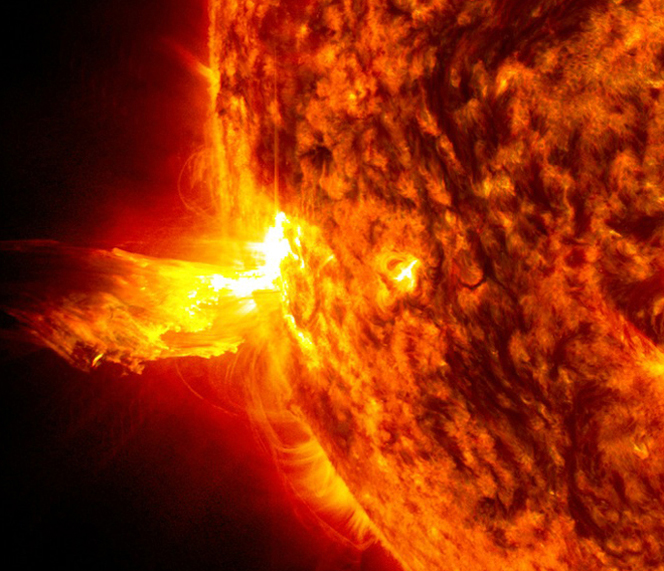

Material rises from the edge of the Sun, as seen in extreme ultraviolet light by NASA’s Solar Dynamics Observatory.

what is a radiation storm?

Radiation Storms

Solar eruptions can accelerate charged particles — electrons and protons — into space at incredibly high speeds, initiating a radiation storm.

The fastest particles travel so quickly they can zip across roughly 93 million miles from the Sun to Earth in about 30 minutes or less.

This animation shows energetic particles from the Sun affecting a spacecraft.

The NASA/ESA Solar and Heliospheric Observatory captured this video of a coronal mass ejection on March 13, 2023. The bright dot to the lower right is the planet Mercury.

Solar Activity Cycle

Solar storms and their related phenomena all wax and wane with the Sun’s 11-year cycle of activity. Such events are more common during solar maximum (or peak of the solar cycle) but are less frequent during solar minimum (or low point of the cycle).

Sunspots, or dark “blemishes” on the Sun, also increase during solar maximum and mark magnetically active regions on the Sun, which give rise to solar eruptions. When a large group of sunspots or a particularly active region on the Sun comes into view, it’s a good time to be on the lookout for solar storms that could be headed our way.

How NASA Studies Solar Storms

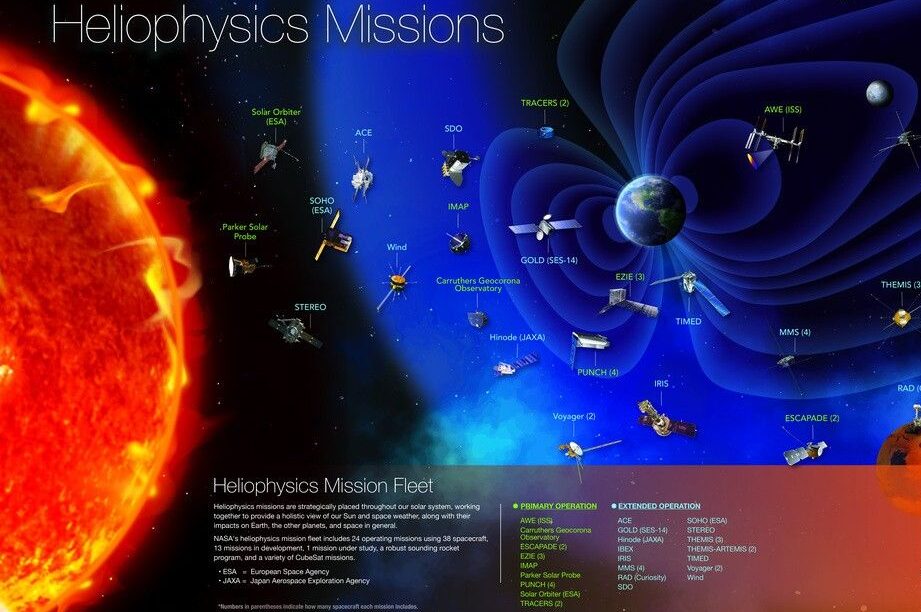

A high-resolution graphic showing NASA’s heliophysics fleet with a text bar and color code indicating new and current missions. Mapping out this interconnected system requires a holistic study of the Sun’s influence on space, Earth and other planets. NASA has a fleet of spacecraft strategically placed throughout our heliosphere—from Parker Solar Probe at the Sun observing the very start of the solar wind, to satellites around Earth, to the farthest human-made object, Voyager, which is sending back observations on interstellar space. Each mission is positioned at a critical, well-thought out vantage point to observe and understand the flow of energy and particles throughout the solar system—all helping us untangle the effects of the star we live with.

The Sun

The Sun is a dynamic star, made of super-hot ionized gas called plasma.

The Sun’s surface and atmosphere change continually, driven by the magnetic forces generated by this constantly-moving plasma. The Sun releases energy in two ways: the usual flow of light that illuminates the Earth and makes life possible; but also in more violent and dramatic ways — it gives off bursts of light, particles, and magnetic fields that can have ripple effects all the way out to the solar system’s magnetic edge.

Solar Science

The Sun is a dynamic star, made of super-hot ionized gas called plasma. The Sun’s surface and atmosphere change continually, driven by the magnetic forces generated by this constantly-moving plasma. The Sun releases energy in two ways: the usual flow of light that illuminates the Earth and makes life possible; but also in more violent and dramatic ways—it gives off bursts of light, particles, and magnetic fields that can have ripple effects all the way out to the solar system’s magnetic edge. We study the Sun to better understand how its ever-changing conditions can influence Earth, other worlds, and even space itself.

NASA studies the Sun for numerous reasons. For one thing, its influence on the habitability of Earth is incredibly complex, providing radiation that depending on the amount can be either a boon or hazard to the development of life. Second, this radiation, and the accompanying energy and magnetic fields that the Sun sends out — is intense and dynamic, with the ability to create changes in the space weather around us, and interfere with our space technology and communications systems. Finally, we study this star we live with, because it’s the only star we can study up close. Studying our Sun informs research about other stars throughout the universe.

The Sun’s activity and conditions vary on almost every timescale, from tiny changes that happen over milliseconds, to solar eruptions that last hours or days, to its 27-day rotation. The solar magnetic field cycles through a complete change in direction and back about every 22 years, which in turn gives rise to the roughly 11-year cycle in solar activity. As magnetic field becomes more complex, it releases energy near the solar surface. These solar explosions can take the form of solar flares, coronal mass ejections, or releases of incredibly fast charged particles that race out from the Sun at nearly the speed of light.

NASA watches the Sun nearly 24-seven with a fleet of solar observatories, studying everything from the Sun’s tenuous outer atmosphere, to its roiling surface, and even peering inside the Sun using magnetic and helioseismic instruments.

On a mission to “touch the Sun,” NASA’s Parker Solar Probe became the first spacecraft to fly through the corona — the Sun’s upper atmosphere — in 2021. With every orbit bringing it closer, the probe faces brutal heat and radiation to provide humanity with unprecedented observations, visiting the only star we can study up close.

What Is Parker Solar Probe?

NASA’s Parker Solar Probe will revolutionize our understanding of the Sun. The spacecraft is gradually orbiting closer to the Sun’s surface than any before it – well within the orbit of Mercury.

What Is the Solar Wind?

From the center of the solar system, rages a powerful wind. Sent by the Sun, this wind whips at speeds exceeding one million miles per hour as it traverses to the edge of interstellar space bathing everything in its path.

This is the solar wind.

It also makes critical contributions to forecasting changes in the space environment that affect life and technology on Earth.

- Parker will fly more than seven times closer to the Sun than any spacecraft.

- Over seven years, the spacecraft will complete 24 orbits around the Sun.

- At its closest approach, the spacecraft will come within about 3.9 million miles (6.2 million kilometers) of the Sun.

| Nation | United States of America (USA) |

| Objective(s) | Solar Orbit |

| Spacecraft | Parker Solar Probe (Solar Probe Plus) |

| Spacecraft Mass | 1,510 pounds (685 kilograms) at launch |

| Mission Design and Management | NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center / Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory |

| Launch Vehicle | Delta IV-Heavy with Upper Stage |

| Launch Date and Time | Aug. 12, 2018 / 7:31 UTC |

| Launch Site | Cape Canaveral Air Force Station, Fla. |

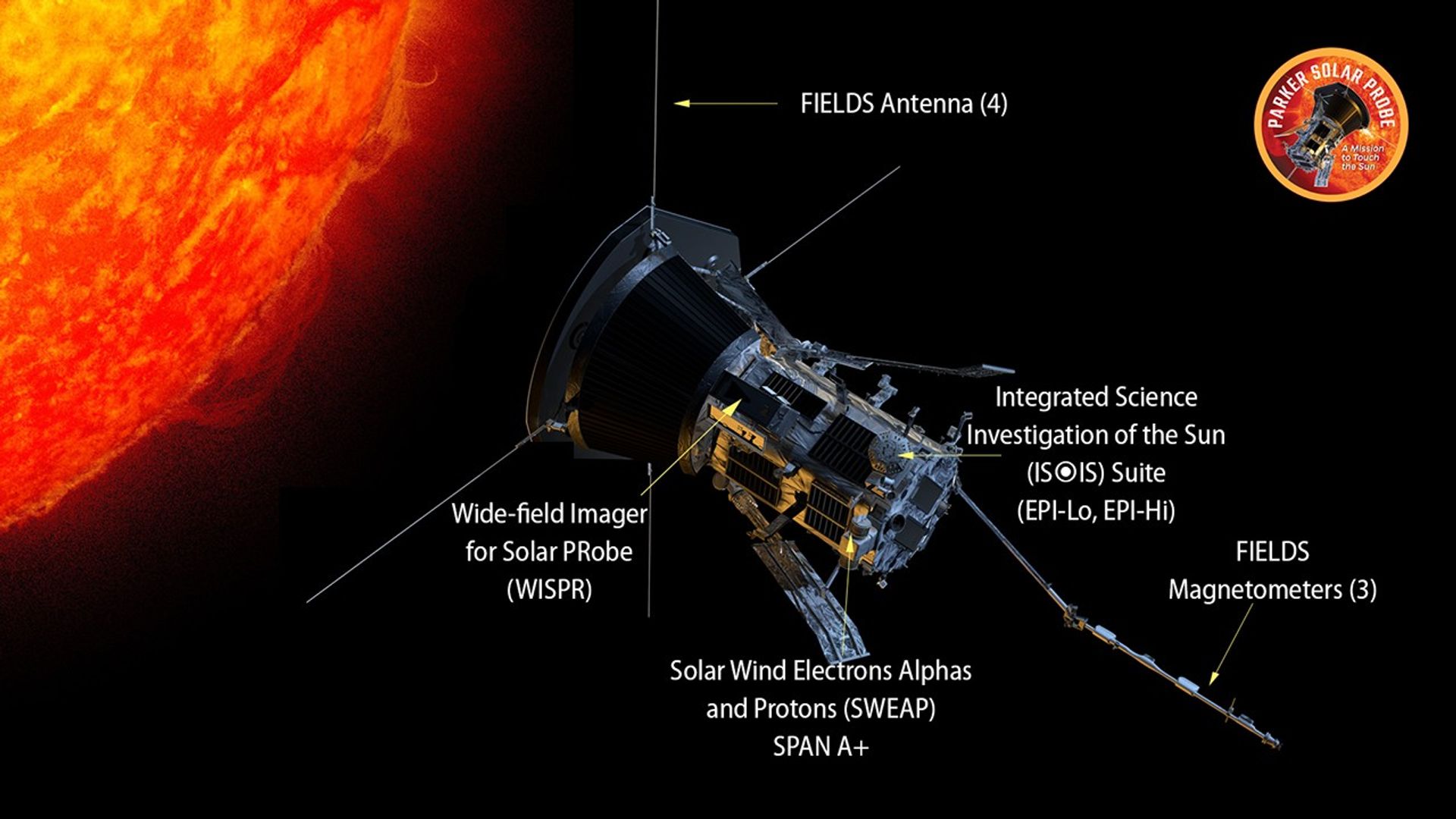

| Scientific Instruments | 1. Fields Experiment (FIELDS) 2. Integrated Science Investigation of the Sun (IS☉IS ) 3. Wide Field Imager for Solar Probe (WISPR) 4. Solar Wind Electrons Alphas and Protons (SWEAP) |

At closest approach, Parker Solar Probe hurtles around the Sun at approximately 430,000 mph (700,000 kph). That’s fast enough to get from Philadelphia to Washington, D.C., in one second.

Through the solar wind, the Sun touches every part of our solar system.

The solar wind’s many impacts include creating auroras and stripping planets’ atmospheres.

Here’s a look at where it comes from and how it influences everything from our space environment to our lives at home. The solar wind starts its journey at the Sun.

It emanates from features on the Sun such as dark and cool regions called coronal holes and active regions, which are characterized by strong magnetic fields.

These regions release solar wind with different speeds and densities. But all release the same basic components of solar wind — electrically charged particles such as protons and electrons.

View of the Solar Wind

NASA’s Parker Solar Probe — the spacecraft that has made it closest to the Sun — caught this view of the solar wind during one of its close solar encounters. The feature seen in the middle of the screen at the start is the galactic plane. The solar wind can be seen streaming in from the left side.

As the solar wind gushes out, it drags the Sun’s magnetic field with it. The stretched out solar magnetic field ends up in the shape of a spiral due to the Sun’s rotation.

This spiral was named after preeminent solar scientist Eugene Parker, who developed the first theory of the solar wind in 1958. The first measurement confirming the existence of the solar wind came the following year, with the launch of the first spacecraft to leave Earth’s orbit.

Since the solar wind’s particles are charged, they follow these spiraled magnetic field lines as they burst out from the Sun. As they travel, the particles and magnetic field can create what are known as plasma waves. These waves occur as fluctuating electric and magnetic fields plow through clumps of ions and electrons, pushing some to accelerated speeds. These sounds, as recorded by Parker Solar Probe, are created as plasma waves interact with the solar wind. The different sounds here are caused by three types of plasma waves: dispersive chirping waves, Langmuir waves, and whistler mode waves.

These plasma waves, like the roaring ocean surf, create a rhythmic cacophony that — with the right tools — we can “hear.” Parker Solar Probe is one spacecraft that can “hear” and record when waves and particles interact with one another in the solar wind.

The Solar Wind’s Journey Continues

- As the solar wind races out from the Sun, its first major encounter is with Mercury.Once inside, the particles spiral in toward the poles, where they can contribute to the glowing lights of the auroras when they smash into particles in the atmosphere.

At Earth, the solar wind’s collisions have much larger impacts.

Earth’s magnetosphere is much stronger than Mercury’s, so most of the solar wind is deflected.

But some particles sneak through.

Once inside, the particles spiral in toward the poles, where they can contribute to the glowing lights of the auroras when they smash into particles in the atmosphere.

The solar wind can also affect power grids on Earth.

When an especially fast and dense gust of solar wind passes Earth, it can temporarily compress Earth’s magnetic field. The resulting change in Earth’s magnetic field strength can burn out transformer stations in the power grid leading to blackouts.

On the Moon, where there’s almost no atmosphere, the solar wind frequently reaches the surface.

When this electric breeze blasts into lunar rocks, it can break atomic bonds and create water. In 2020, NASA’s Stratospheric Observatory For Infrared Astronomy (SOFIA) mission discovered water created this way on the sunlit lunar surface. The solar wind also charges the lunar landscape with static electricity. Both of these effects lessen when the Moon tucks inside Earth’s protective magnetic environment for several days each month.

Similarly, at Mars the solar wind is also slowly destroying and blowing away the Martian atmosphere.

In the past, the Red Planet was warm and wet. But without a strong magnetosphere to protect it, Mars’ atmosphere is constantly eroded by the solar wind’s bombardment. About a quarter of a pound of atmosphere is lost every second — and more when there’s a strong solar storm.

NASA is developing ways to protect astronauts from the solar wind as they travel from the Moon to Mars. NASA also takes measurements of the solar wind around the solar system to help better understand the risks it poses to interplanetary travelers.

NASA has overcome many difficult engineering challenges when it comes to human spaceflight – one that remains is how to best protect astronauts from space radiation.

A team at NASA’s Langley Research Center in Hampton, Virginia is working on one potential solution – a next-generation wearable radiation protection garment to protect against solar particle events.

A decade ago, a radiation protection vest was developed but it was never used. It served its purpose but was bulky and somewhat awkward. Now, a research team has completed a new prototype, using the previous version as a starting point. Sewn in-house, it is more streamlined, no longer uses Velcro or zippers making it easier to don quickly, and it provides more protection.

“The radiation protection garments being developed can protect astronauts during every phase of the upcoming Artemis missions,” said Martha Clowdsley, project manager.

After several iterations and piecing multiple patterns and ideas together, the prototype is ready for ground testing.

“The materials used are hydrogen-rich,” said Julie Hanson, project technical lead and human factor psychologist/engineer.

Hanson researches how people interact with technology. “We need to keep that in mind when designing,” she said.

As a result, the vest includes many layers and allows for movement and fit.

“It’s really trial and error, different fabrics fit and give differently, you can’t just make it out of anything,” said Crystal Chamberlain, senior technician. Chamberlain, who has worked on thermal and structures and materials analysis, has been sewing since she was six years old and now finds herself in the role of space seamstress.

The project started about a year ago and has a multi-disciplinary team. Sheila Thibeault, a physicist, is contributing to the research. The team also received input from middle and high school students who participated in a challenge this summer, designing garments to help mitigate radiation exposure during deep space missions.

“It was challenging and cool learning about radiation and ways to prevent it,” said Randy, an eighth-grader at Central Junior High in Pollock, Texas. Now having met with other teams and researchers at NASA he has ideas about things he’d change with his team’s design.

The students and researchers learned from one another. One of the WEAR teams came up with the idea to use sweat as insulation in a cotton layer worn under clothes with duct tape as a reservoir holder – something the NASA team hadn’t thought of. However, longevity and cost are factors in the wearables that many students didn’t consider.

If the prototype is successful, it might be manufactured for use by a commercial company.

“We need radiation protection for every mission,” Hanson said.

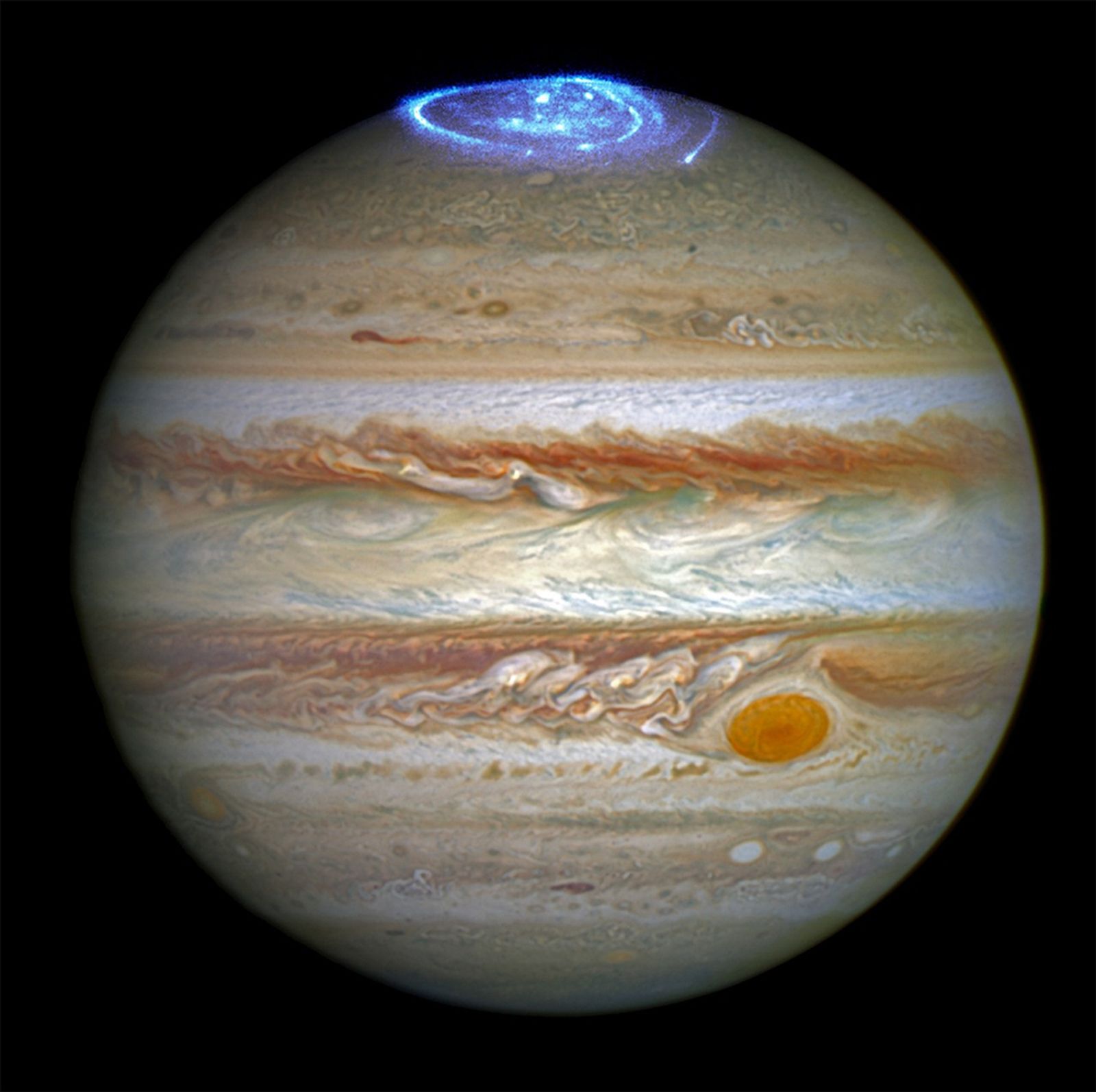

Farther afield, the solar wind blows past the gas giants.

Auroras have been seen around Jupiter’s poles, caused by the same phenomenon as auroras on Earth.

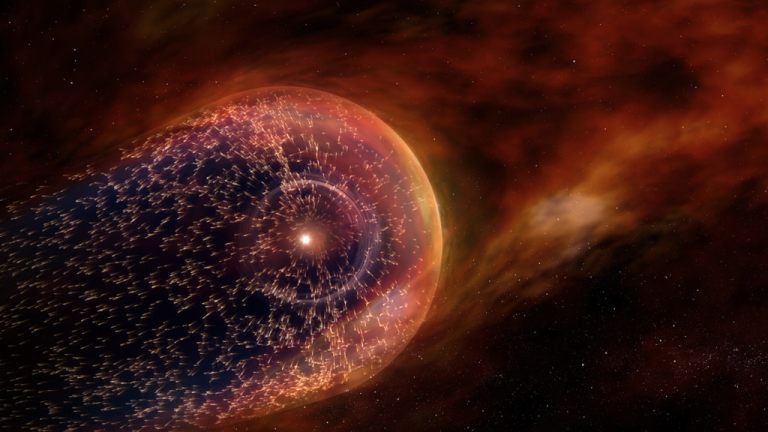

The solar wind’s journey ends at the edge of our solar system — the heliopause.

The heliopause is the outer boundary of the heliosphere — the bubble of influence created by the solar wind that protects our solar system from the majority of cosmic radiation. At the heliopause, the solar wind’s pressure is matched by the winds of other stars.

The heliosphere changes size and shape as the solar wind waxes and wanes in strength. So far, only a couple spacecraft have made it beyond the heliopause. Launched in 1977, Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 took about 15 years to travel to this boundary where they collected the first direct evidence of the heliopause.

Today, scientists are still working to understand this important region. NASA’s upcoming Interstellar Mapping and Acceleration Probe (IMAP) will aid in this work by mapping the heliopause from afar. With its data, scientists hope to better understand how the solar wind interacts with interstellar space to create our protective heliosphere.

For the first time in history, a spacecraft has touched the Sun. On a mission to “touch the Sun,” NASA’s Parker Solar Probe became the first spacecraft to fly through the corona — the Sun’s upper atmosphere — in 2021. With every orbit bringing it closer, the probe faces brutal heat and radiation to provide humanity with unprecedented observations, visiting the only star we can study up close.

Parker Solar Probe Instruments

Parker Solar Probe works under extreme conditions as it gathers data in the Sun’s corona, grazing closer to our star than any spacecraft before. Its four instrument suites characterize the dynamic region close to the Sun by measuring particles and electric and magnetic fields, and each was specially designed to withstand the harsh radiation and temperatures they encounter.

An artist’s concept shows the locations of science instruments on the Parker Solar Probe.

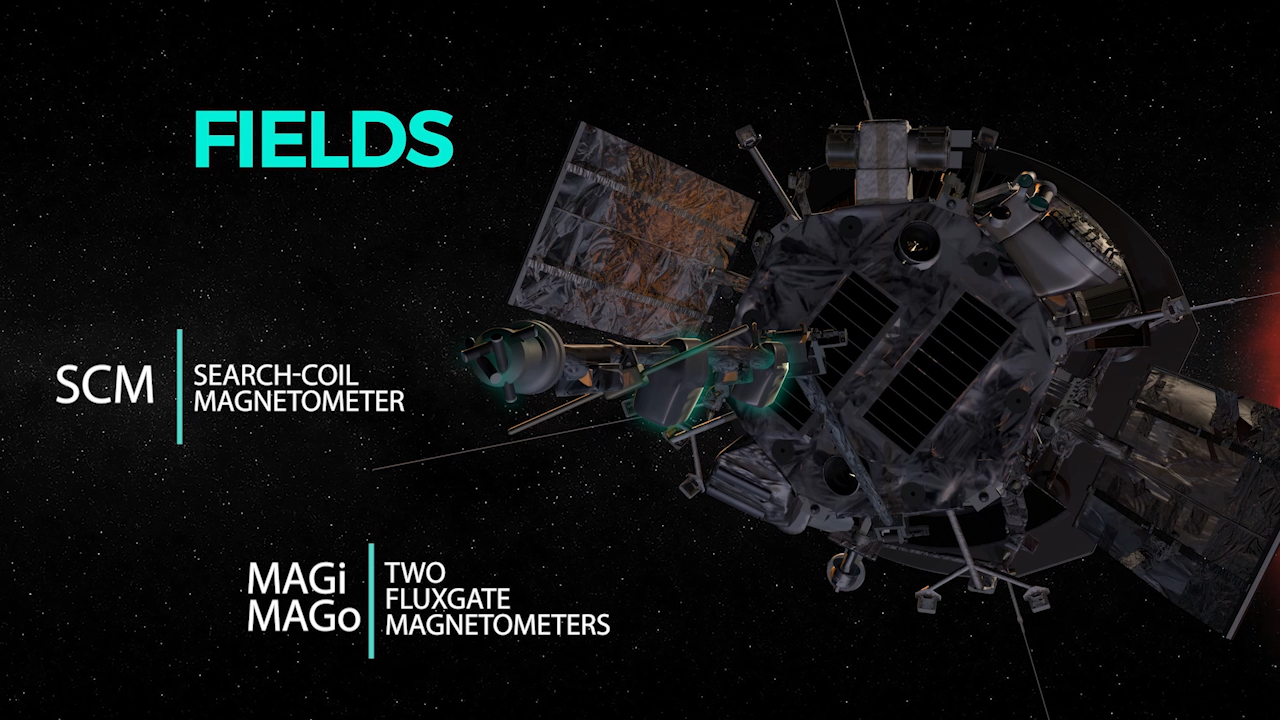

FIELDS

Surveyor of the invisible forces, the FIELDS instrument suite captures the scale and shape of electric and magnetic fields in the Sun’s atmosphere. FIELDS measures waves and turbulence in the inner heliosphere with high time resolution to understand the fields associated with waves, shocks, and magnetic reconnection, a process by which magnetic field lines explosively realign.

Surveyor of the invisible forces, the FIELDS instrument suite captures the scale and shape of electric and magnetic fields in the Sun’s atmosphere. FIELDS measures the electric field around the spacecraft with five antennas, four of which stick out beyond the spacecraft’s heat shield and into the sunlight, where they experience temperatures of 2,500 °F. The 2-meter-long antennas are made of a niobium alloy, which can withstand extreme temperatures. FIELDS measures electric fields across a broad frequency range both directly, or in situ, and remotely. Operating in two modes, the four sunlit antennas measure the properties of the fast and slow solar wind — the flow of solar particles constantly streaming out from the Sun. The fifth antenna, which sticks out perpendicular to the others in the shade of the heat shield, helps make a three-dimensional picture of the electric field at higher frequencies.

A trio of magnetometers, each about the size of a fist, help FIELDS assess the magnetic field. A search-coil magnetometer, or SCM, measures how the magnetic field changes over time. Since changing magnetic fields induce a voltage in the coil, it’s possible to track how the magnetic field changes by measuring that voltage. Two identical fluxgate magnetometers, MAGi and MAGo, measure the large-scale coronal magnetic field. The fluxgate magnetometers are specialized for measuring the magnetic field farther from the Sun where it varies at a slower rate, while the search-coil magnetometer is necessary closer to the Sun where the field changes quickly, as it can sample the magnetic field at a rate of two million times per second.

FIELDS was designed, built, and is operated by a team lead by the Space Sciences Laboratory at the University of California, Berkeley (principal investigator Stuart D. Bale).

WISPR

The Wide-Field Imager for Parker Solar Probe is the only imaging instrument aboard the spacecraft. WISPR looks at the large-scale structure of the corona and solar wind before the spacecraft flies through it. About the size of a shoebox, WISPR takes images from afar of structures like coronal mass ejections (CMEs), jets, and other ejecta from the Sun. These structures travel out from the Sun and eventually overtake the spacecraft, where the spacecraft’s other instruments take in-situ measurements. WISPR helps link what’s happening in the large-scale coronal structure to the detailed physical measurements being captured directly in the near-Sun environment.

The Wide-Field Imager for Parker Solar Probe is the only imaging instrument aboard the spacecraft. WISPR looks at the large-scale structure of the corona and solar wind before the spacecraft flies through it. To image the solar atmosphere, WISPR uses the heat shield to block most of the Sun’s light, which would otherwise obscure the much fainter corona. Specially designed baffles and occulters reflect and absorb the residual stray light that has been reflected or diffracted off the edge of the heat shield or other parts of the spacecraft.

WISPR uses two cameras with radiation-hardened Active Pixel Sensor CMOS detectors. These detectors are used in place of traditional CCDs because they are lighter and use less power. They are also less susceptible to effects of radiation damage from cosmic rays and other high-energy particles, which are a big concern close to the Sun. The camera’s lenses are made of a radiation hard BK7, a common type of glass used for space telescopes, which is also sufficiently hardened against the impacts of dust.

WISPR was designed and developed by the Solar and Heliophysics Physics Branch at the Naval Research Laboratory in Washington, D.C. (principal investigator Russell Howard), which also developed the observing program.

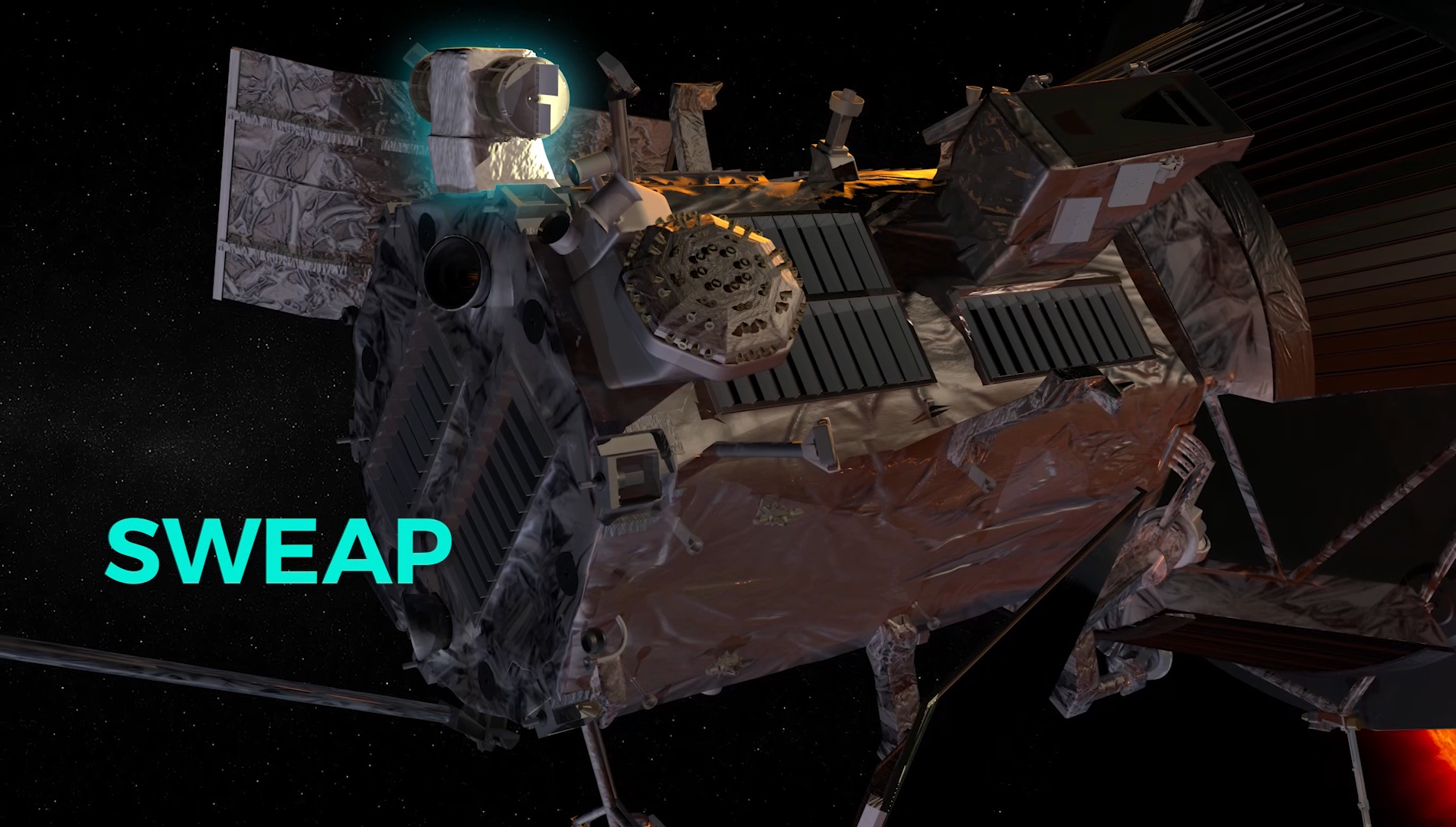

SWEAP

The Solar Wind Electrons Alphas and Protons investigation, or SWEAP, gathers observations using two complementary instruments: the Solar Probe Cup, or SPC, and the Solar Probe Analyzers, or SPAN. The instruments count the most abundant particles in the solar wind — electrons, protons, and helium ions — and measure such properties as velocity, density, and temperature to improve our understanding of the solar wind and coronal plasma.

The Solar Wind Electrons Alphas and Protons investigation, or SWEAP, counts the most abundant particles in the solar wind — electrons, protons, and helium ions — and measure such properties as velocity, density, and temperature to improve our understanding of the solar wind and coronal plasma.

SPC is what’s known as a Faraday cup, a metal device that can catch charged particles in a vacuum. Peeking over the heat shield to measure how electrons and ions are moving, the cup is exposed to the full light, heat, and energy of the Sun. The cup is composed of a series of highly transparent grids — one of which uses variable high voltages to sort the particles — above several collector plates, which measure the particles’ properties. The variable voltage grid also helps sort out background noise, such as cosmic rays and photoionized electrons, which could otherwise bias the measurements. The grids, located near the front of the instrument, can reach temperatures of 3,000 °F, glowing red while the instrument makes measurements. The instrument uses pieces of sapphire to electrically isolate different components within the cup. As it passes close to the Sun, SPC takes up to 146 measurements per second to accurately determine the velocity, density, and temperature of the Sun’s plasma.

SPAN is composed of two instruments, SPAN-A and SPAN-B, which have wide fields of view to allow them to see the parts of space not observed by SPC. Particles encountering the detectors enter a maze that sends the particles through a series of deflectors and voltages to sort the particles based on their mass and charge. While SPAN-A has two components to measure both electrons and ions, SPAN-B looks only at electrons.

SWEAP was built mainly at the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and at the Space Sciences Laboratory at the University of California, Berkeley. The institutions jointly operate the instrument. The principal investigator is Justin Kasper from the University of Michigan.

ISʘIS

The Integrated Science Investigation of the Sun — ISʘIS, pronounced “ee-sis” and including the symbol for the Sun in its acronym — uses two complementary instruments in one combined scientific investigation to measure particles across a wide range of energies. By measuring electrons, protons, and ions, ISʘIS will understand the particles’ lifecycles — where they came from, how they became accelerated, and how they move out from the Sun through interplanetary space. The two energetic particle instruments on ISʘIS are called EPI-Lo and EPI-Hi (EPI stands for Energetic Particle Instrument).

The Integrated Science Investigation of the Sun — IS☉IS, pronounced ee-sis and including the symbol for the Sun in its acronym — on board Parker Solar Probe uses two complementary instruments in one combined scientific investigation to measure particles across a wide range of energies.

EPI-Lo measures the spectra of electrons and ions and identifies carbon, oxygen, neon, magnesium, silicon, iron, and two isotopes of helium, He-3 and He-4. Distinguishing between helium isotopes will help determine which of several theorized mechanisms caused the particles’ acceleration. The instrument has a unique design — much like a sea urchin — with an octagonal dome body supporting 80 viewfinders, each about the size of a dime. Multiple viewfinders provide a wide field of view to observe low-energy particles. An ion that enters EPI-Lo through one of the viewfinders first passes through two carbon-polyimide-aluminum foils and then encounters a solid-state detector. Upon impact, the foils produce electrons, which are measured by a microchannel plate. Using the amount of energy left by the ion’s impact on the detector and the time it takes the ions to pass through the sensor identifies the species of the particles.

EPI-Hi uses three particle sensors composed of stacked layers of detectors to measure particles with energies higher than those measured by EPI-Lo. The front few layers are composed of ultra-thin silicon detectors made up of geometric segments, which allows for the determination of the particle’s direction and helps reduce background noise. Charged particles are identified by measuring how deep they travel into the stack of detectors and how many electrons they pull off atoms in each detector, a process called ionization. At closest approach to the Sun, EPI-Hi will be able to detect up to 100,000 particles per second.

By using these two instruments together, ISʘIS investigates all energies of solar energetic particles as well as high-energy solar wind particles that cannot be detected by SWEAP.

ISʘIS is led by Princeton University in Princeton, New Jersey (principal investigator David McComas), and was built largely at the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory in Laurel, Maryland, and Caltech in Pasadena, California, with significant contributions from Southwest Research Institute in San Antonio, Texas, and NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland. The ISʘIS Science Operations Center is located at the University of New Hampshire in Durham.