The insane biology of: the joint manta Ray

the world of mobula rays transcends the barriers between oceans, the borders between shallow seas and cold Ocean depths and even the oceans ultimate barrier: the one between sea and sky. Found in tropical and temperate around seas. The World the genus mobula contains some of the most incredible organisms that have ever Graced this planet. There are over 600 species of ray in the ocean, but only 11 different species of mobula ray all of which have a distance diamond shaped appearance with wings that allow them to glide through the water, and put on stunning displays of elegance and agility. Some are small and congregation in Incredible numbers, occasionally flying out of the water in balletic leaps. Others are absolutely enormous – so enormous. The giant Oceanic manta ray is the largest species of ray in the world, with wingspans that can reach over 8 metres . Their sheer size makes them a striking presence in the ocean, captivating researchers and divers who are lucky enough to encounter them. But more than just being how they are also gregarious and often as curious about human swimmer as the swimmers are of them. And it turns out giant mantas are much more mysterious then scientist even realized. Until very recently, we didn’t even know how to categorize them. Until 2018 scientist listed giant manta rays and reef manta rays under the genus manta. But more analysis of their morphology and genetics result in scientist place them in the mobula genus along with smaller devil rays. And now scientist are learning that the giant Manta Ray isn’t the animal they once thought it was. It is not simply as shallow water plankton eater but a deep sea renegade, with moment so efficient that teams of roboticists around The World are working to emulate it. And not only does it dive deeper than we ever thought, and move more efficiently to the shock of the science world, giant manta ray have been observed to rapidly change the colour and pattern of there skin something that is basically unheard of in the world of is elasmobranchs. The giant Ocean manta is big, intelligent, and still absolutely full of mystery. Why did giant Ocean manta ray evolve become so enormous? And how does and an enormous body move so efficiently diving to cold, it flaps it’s missive pectoral fins, giving the appearance that it’s flying. When rays diverged from sharks around 200 million years ago, the pectoral fins expanded into what we now call the ray disc. And for the giant oceanic manta ray, this expansion was extreme. Their wing span can reach over 8 m across. There pectoral points makeup around 85% of the body length. For Shark of a similar size, they are pectoral points make up just 10 to 15% of their body length. But what benefit do such miss you wing give vs. the most typical Sharks body plan? I am images by observing the behaviour of the giant manta ray compare to the similarly size great white shark the great white shark is a powerful, fast swimmer but it burshs of speed usually only happen in One direction. It’s hard for the great white shark turn on a dime. Compare this giant manta ray- it’s often seen swimming in tight acrobatic circles-circling back to eat cluster of plankton, or to evade predators. It’s maneuvering and agility are almost unheard of in such large animals and its thanks to the giant manta ray large and flexible wings. While the overall shape of a manta wing is similar to the wing is similar to the wings of birds, these fins can undulate and bend in many more ways than bird wings can. The giant manta ray has numerous support structure inside the pectoral fin, and these structures can all be controlled separately. But as useful as maneuvering is for evading predators, it comes at a cost. Maneuvering is simply controlled instability. And without stability, an animal can’t move steadily and efficiently along predicted path. Luckily, the giant oceanic manta ray strike a balance between these opposing qualities and is maintained stability and efficiency. One way the manta ray maintains stability is by having wings with the valley high aspect ratio. During fight in the sea are in the sky longer narrow wings give a plane or manta ray most stability. It’s sort of like a tightrope Walker who holds a long pole as they walk the extra length helps balance the body. manta ray wings aren’t exactly long and skinny like glidder wings but their length does help balance the animal when gliding. I expect ratio wings also help generate left efficiently. And the way the manta moves its factorial points also love its swimming to the highly efficient and sometimes, surprising fast. On average, giant manta rays swim about 9 miles per avar but danger they can sprint as fast as 22 meter per hour. To reach these speeds they combine fine oscillations with undulations. Oscillations are the flapping of the wing up and down, which generates large propulsive and lift force. But at the same time that the wing is oscillating up and down, it’s also undulating sending a traveling wave outwards from its body to

Protected Status

ESA Threatened

Throughout Its Range

CITES Appendix II

Throughout Its Range

SPAW Annex II

Throughout the Wider Caribbean Region

Quick Facts

Weight

Up to 5,300 pounds

Length

Disc width up to 26 feet

Lifespan

Up to 45 years

Threats

Bycatch, Harvest for international trade, Overfishing

Region

New England/Mid-Atlantic, Pacific Islands, Southeast

About the Species

Giant manta ray in Flower Garden Banks National Marine Sanctuary. Credit: NOAA/George Schmahl

Giant manta ray in Flower Garden Banks National Marine Sanctuary. Credit: NOAA/George Schmahl

Giant manta ray in Flower Garden Banks National Marine Sanctuary. Credit: NOAA/George Schmahl

The giant manta ray is the world’s largest ray with a wingspan of up to 26 feet. They are filter feeders and eat large quantities of zooplankton. Giant manta rays are slow-growing, migratory animals with small, highly fragmented populations that are sparsely distributed across the world.

The main threat to the giant manta ray is commercial fishing, with the species both targeted and caught as bycatch in a number of global fisheries throughout its range. Manta rays are particularly valued for their gill plates, which are traded internationally. In 2018, NOAA Fisheries listed the species as threatened under the Endangered Species Act.

Population Status

The global population size is unknown. With the exception of Ecuador, the few regional population estimates appear to be small, ranging from around 600 to 2,000 individuals, and in areas subject to fishing, have declined significantly. Ecuador, on the other hand, is thought to be home to the largest population of giant manta ray, comprising over 22,000 individuals, with large aggregation sites within the waters of the Machalilla National Park and the Galapagos Marine Reserve. Overall, given their life history traits, particularly their low reproductive output, giant manta ray populations are inherently vulnerable to depletions, with low likelihood of recovery. Additional research is needed to better understand the population structure and global distribution of the giant manta ray.

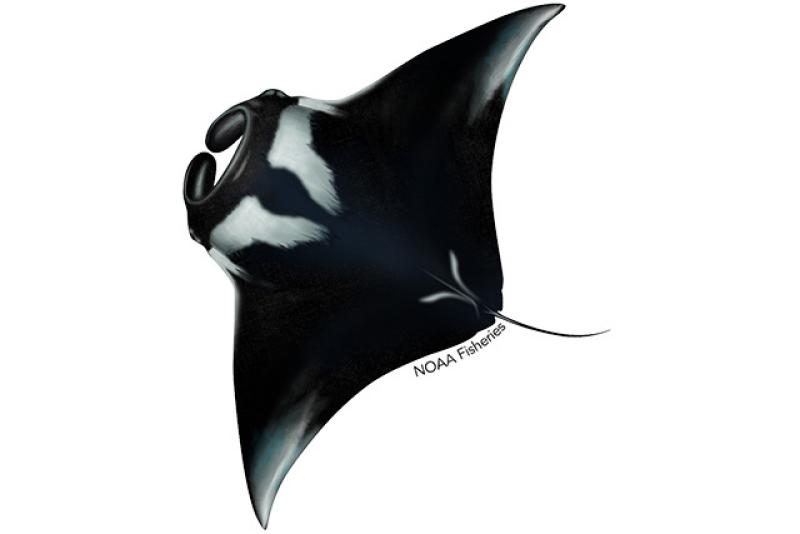

Appearance

Manta rays are recognized by their large diamond-shaped body with elongated wing-like pectoral fins, ventrally-placed gill slits, laterally-placed eyes, and wide, terminal mouths. In front of the mouth, they have two structures called cephalic lobes which extend and help to channel water into the mouth for feeding activities (making them the only vertebrate animals with three paired appendages).

Manta rays come in two distinct color types: chevron (mostly black back and white belly) and black (almost completely black on both sides). They also have distinct spot patterns on their bellies that can be used to identify individuals. There are two species of manta rays: giant manta rays (Mobula birostris) and reef manta rays (Mobula alfredi). Giant manta rays are generally larger than reef manta rays, have a caudal thorn, and rough skin appearance. They can also be distinguished from reef manta rays by their coloration.

Behavior and Diet

The giant manta ray is a migratory species and seasonal visitor along productive coastlines with regular upwelling, in oceanic island groups, and near offshore pinnacles and seamounts. The timing of these visits varies by region and seems to correspond with the movement of zooplankton, current circulation and tidal patterns, seasonal upwelling, seawater temperature, and possibly mating behavior.

Although the giant manta ray tends to be solitary, they aggregate at cleaning sites and to feed and mate. Manta rays primarily feed on planktonic organisms such as euphausiids, copepods, mysids, decapod larvae, and shrimp, but some studies have noted their consumption of small and moderately sized fish as well. When feeding, mantas hold their cephalic fins in an “O” shape and open their mouths wide, creating a funnel that pushes water and prey through their mouth and over their gill plates. Manta rays use many different types of feeding strategies, such as barrel rolling (doing somersaults over and over again) and creating feeding chains with other mantas to maximize prey intake.

Giant manta rays also appear to exhibit a high degree of plasticity or variation in terms of their use of depths within their habitat. During feeding, giant manta rays may be found aggregating in shallow waters at depths less than 10 meters. However, tagging studies have also shown that the species conducts dives of up to 200 to 450 meters and is capable of diving to depths exceeding 1,000 meters. This diving behavior may be influenced by season and shifts in prey location associated with the thermocline.

Where They Live

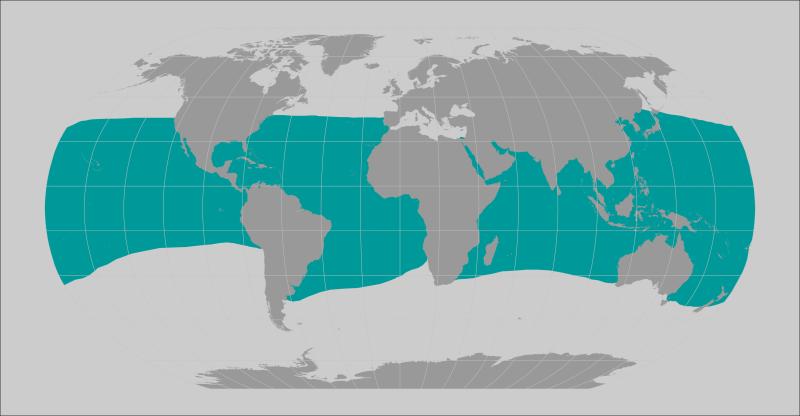

The giant manta ray is found worldwide in tropical, subtropical, and temperate bodies of water and is commonly found offshore, in oceanic waters, and in productive coastal areas. The species has also been observed in estuarine waters, oceanic inlets, and within bays and intercoastal waterways. As such, giant manta rays can be found in cool water, as low as 19°C, although temperature preference appears to vary by region. For example, off the U.S. East Coast, giant manta rays are commonly found in waters from 19 to 22°C, whereas those off the Yucatan peninsula and Indonesia are commonly found in waters between 25 to 30°C.

World map providing approximate representation of the giant manta ray’s range

Lifespan & Reproduction

Manta rays have among the lowest fecundity of all elasmobranchs (a subclass of cartilaginous fish), typically giving birth to only one pup every two to three years. Gestation is thought to last around a year. Although manta rays have been reported to live at least 45 years, not much is known about their growth and development.

Threats

Overfishing and Bycatch

The most significant threat to the giant manta ray is overutilization for commercial purposes. Giant manta rays are both targeted and caught as bycatch in a number of global fisheries throughout their range, and are most susceptible to artisanal/small-scale fisheries and commercial fisheries, particularly purse seines, gill nets, longlines, and trawls.

Efforts to address overutilization of the species through current regulatory measures are inadequate, as targeted fishing and illegal retainment of the species still occurs despite prohibitions in a significant portion of the species’ range. Also, measures to address and minimize bycatch of the species in commercial fisheries are rare.

Harvest for International Trade

Demand for the gill plates of manta and other mobula rays has risen dramatically in Asian markets. With this expansion of the international gill plate market and increasing demand for manta ray products, estimated harvest of giant manta rays, particularly in many portions of the Indo-Pacific and Eastern Pacific, has led to massive declines in manta ray populations and fishery collapse.

Other potential threats that should be monitored include entanglement, vessel strikes, marine debris/pollution, climate change, recreational fishing interactions, tourism, and the aquarium trade.

Giant Manta Ray Threats

Scientific Classification

| Kingdom | Animalia |

|---|---|

| Phylum | Chordata |

| Class | Chondrichthyes |

| Order | Rajiformes |

| Family | Mobulidae |

| Genus | Mobula |

| Species | birostris |

Last updated 08/25/2025

Additionally, the giant manta ray is listed under:

- Appendix II of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES)

- Annex II of the Protocol for Specially Protected Areas and Wildlife (SPAW)

Recovery Planning and Implementation

Recovery Outline

Under the ESA, NOAA Fisheries is required to develop and implement recovery plans for the conservation and survival of listed species. NOAA Fisheries has developed a recovery outline to serve as an interim guidance document to direct recovery efforts, including recovery planning, for the giant manta ray until a full recovery plan is developed and approved. The recovery outline presents a preliminary strategy for recovery of the species and recommends high priority actions to stabilize and recover the species.

Draft Recovery Plan

We developed a Draft Recovery Plan in October 2024 (89 FR 82991). We are soliciting review and comment from the public and all interested parties on the Draft Recovery Plan. We will consider all substantive comments accepted through December 16, 2024, before submitting the Recovery Plan for final approval.

The Draft Recovery Plan follows the 3-part framework approach to recovery planning, in which recovery planning components are divided into three separate documents. The Draft Recovery Plan provides the foundation and overall road map for achieving the recovery goal. It contains the elements required to be in a recovery plan under the Endangered Species Act: (1) objective, measurable recovery criteria; (2) site-specific management actions necessary to conserve the species; and (3) estimates of the time and costs required to achieve the plan’s goals.

Draft Recovery Implementation Strategy

The Draft Recovery Implementation Strategy is a flexible, operational document that steps-down the recovery actions into more specifically defined activities that implement and support the recovery actions. The Recovery Implementation Strategy is intended to assist NOAA Fisheries and other stakeholders in planning and implementing activities to carry out the recovery actions in the recovery plan. The activities identified in the Recovery Implementation Strategy can be modified and adapted over time based on the progress of recovery and the availability of resources or new data or literature.

Recovery Status Review

Using the 2017 Status Review Report for the giant manta ray as a foundation, we developed an up-to-date Recovery Status Review for the species. A Recovery Status Review is a stand-alone document that provides all the detailed information on the species’ biology, ecology, status and threats, and conservation efforts to date. This document was published in October 2024 and will be updated as necessary with new information. Traditionally, this information was included in the background of a recovery plan and became outdated quickly. As a stand-alone, living document, information can be kept more relevant.

Species Recovery Contacts

- Adrienne Lohe, Giant Manta Ray Recovery Coordinator

For more information on giant manta rays in our regions:

- Calusa Horn, Southeast Region

- Chelsey Young, Pacific Islands Region

Conservation Efforts

At the 2013 meeting of the Conference of the Parties to the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES), the Parties agreed to include all manta rays (Manta spp.) in Appendix II of CITES, with the listing effective on September 14, 2014. The inclusion of manta rays in CITES Appendix II will help ensure that the international trade in these species is legal and sustainable.

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service is the government agency designated under the ESA to carry out the provisions of CITES. NOAA Fisheries provides guidance and scientific support on marine issues given our technical expertise.

Key Actions and Documents

Available Draft Recovery Plan for the Giant Manta Ray and Notice of Initiation of a 5-Year Review

We, NOAA Fisheries, announce the availability of a Draft Endangered Species Act (ESA) Recovery Plan (Draft Recovery Plan) for the threatened giant manta ray (Mobula birostris) for public review. We are soliciting review and comment from the public and…

Determination on the Designation of Critical Habitat for Giant Manta Ray

We, NOAA Fisheries, have determined that a designation of critical habitat is not prudent at this time. Based on a comprehensive review of the best scientific data available, we find that there are no identifiable physical or biological features that…

Notice,

New England/Mid-Atlantic

Pacific Islands

Southeast

Published

December 5, 2019

Final Rule to List the Giant Manta Ray as Threatened Under the Endangered Species Act

On January 22, 2018, NOAA Fisheries issued a final rule to list the giant manta ray (Manta birostris) as threatened under the Endangered Species Act. On November 22, 2023, we issued a direct final rule to revise the scientific name of the giant manta…

- Direct Final Rule to Revise Taxonomy (88 FR 81351, 11/22/2023)

- Final Rule (83 FR 2916, 01/22/2018)

- Proposed Rule (82 FR 3694, 01/12/2017)

- 90-day Finding (81 FR 8874, 02/23/2016)

Final Rule,

New England/Mid-Atlantic

Pacific Islands

Southeast

West Coast

less than 0.5 ounces and collected by scientists and trained fishery observers using non-invasive methods.

Gear Modification

Given that fishing mortality is the main threat to the species, NOAA Fisheries is funding studies to explore bycatch mitigation methods to decrease the number of interactions between fishing gear and giant manta rays. One such study is currently testing the efficacy of bycatch sorting grids to quickly and accurately sort and release mobula rays from purse seine vessels operating in the Pacific. Reducing the handling time of manta rays when caught by fishing vessels can help decrease post-release mortality rates. For this study, NOAA is partnering with the International Seafood Sustainability Foundation (ISSF), in collaboration with researchers from the University of California at Santa Cruz, AZTI research institute, industry partner American Tunaboat Association, and U.S. purse seine vessel owners.

Citizen Science and Reporting

By reporting sightings of giant manta rays, members of the public can help researchers gather valuable data on distribution patterns and habitat use.

Please report manta ray sightings to manta.ray@noaa.gov. To the extent possible, please include the following information: When and where did you see the manta? How big was it? What condition was it in (e.g., any injuries or unusual behavior)? Photos are also helpful and can be used to identify individual manta rays.

The collection of manta ray sighting information is authorized under the OMB Control Number included in the Citizen Science & Crowdsourcing Information Collection page. This information helps inform recovery efforts for this threatened species.

Smooth Skin:

Their skin is smooth, with dark dorsal (upper) surfaces and white ventral (under) surfaces, often featuring unique spots that act like fingerprints for individual identification.

The giant oceanic manta ray, giant manta ray, or oceanic manta ray (Mobula birostris) is a species of ray in the family Mobulidae and the largest type of ray in the world. It is circumglobal and is typically found in tropical and subtropical waters but can also be found in temperate waters.[4] Until 2017, the species was classified in the genus Manta, along with the smaller reef manta ray (Mobula alfredi). DNA testing revealed that both species are more closely related to rays of the genus Mobula than previously thought. As a result, the giant manta was renamed Mobula birostris to reflect the new classification.[5]

Description

The giant oceanic manta ray can grow up to a maximum of 9 m (30 ft) in length[6] and to a disc size of 7 m (23 ft) across with a weight of about 3,000 kg (6,600 lb),[7][8] but the average size commonly observed is 4.5 m (15 ft).[9] It is dorsoventrally flattened and has large, triangular pectoral fins on either side of the disc. At the front, it has a pair of cephalic fins which are forward extensions of the pectoral fins. These can be rolled up in a spiral for swimming or can be flared out to channel water into the large, forward-pointing, rectangular mouth when the animal is feeding. The teeth are in a band of 18 rows and are restricted to the central part of the lower jaw. The eyes and the spiracles are on the side of the head behind the cephalic fins, and the gill slits are on the ventral (under) surface. It has a small dorsal fin and the tail is long and whip-like. The manta ray does not have a spiny tail as do the closely related devil rays (Mobula spp.) but has a knob-like bulge at the base of its tail.[10]

The skin is smooth with a scattering of conical and ridge-shaped tubercles. The colouring of the dorsal (upper) surface is black, dark brown, or steely blue, sometimes with a few pale spots and usually with a pale edge. The ventral surface is white, sometimes with dark spots and blotches. The markings can often be used to recognise individual fish.[11] Mobula birostris is similar in appearance to Mobula alfredi and the two species may be confused as their distribution overlaps. However, there are distinguishing features.

Physical distinctions between oceanic manta ray and reef manta ray

The oceanic manta ray is larger than the reef manta ray, 4 to 5 metres in average compared to 3 to 3.5 metres.[12] However, if the observed rays are young, their size can easily bring confusion. Only the colour pattern remains an effective way to distinguish them. The reef manta ray has a dark dorsal side with usually two lighter areas on top of the head, looking like a nuanced gradient of its dark dominating back coloration and whitish to greyish, the longitudinal separation between these two lighter areas forms a kind of “Y”. While for the oceanic manta ray, the dorsal surface is deep dark and the two white areas are well marked without gradient effect. The line of separation between these two white areas forms a “T”.

The two species can also be differentiated by their ventral coloration. The reef manta ray has a white belly often with spots between the branchial gill slits and other spots spread across trailing edge of pectoral fins and abdominal region. The oceanic manta ray has also a white ventral coloration with spots clustered around lower region of its abdomen. Its cephalic fins, inside of its mouth and its gill slits, are often black.

Distribution and habitat

The giant oceanic manta ray has a widespread distribution in tropical and temperate waters worldwide. In the Northern Hemisphere, it has been recorded as far north as southern California and New Jersey in the United States, Aomori Prefecture in Japan, the Sinai Peninsula in Egypt, and the Azores in the northern Atlantic. In the Southern Hemisphere, it occurs as far south as Peru, Uruguay, South Africa, and New Zealand.[2]

It is an ocean-going species and spends most of its life far from land, travelling with the currents and migrating to areas where upwellings of nutrient-rich water increase the availability of zooplankton.[13] The oceanic manta ray is often found in association with offshore oceanic islands.[10]

Captivity

There are few public aquariums with giant manta ray in captivity. Since 2009, captive manta rays have been classified as Ꮇ. alfredi.[citation needed]

Since 2018 Ꮇ. birostris has been exhibited at Nausicaá Centre National de la Mer in France and Okinawa Churaumi Aquarium in Japan.[14][15] There are also reports that they were kept at the Marine Life Park, part of the Resorts World Sentosa in Singapore.[16][17]

Biology

When traveling in deep water, the giant oceanic manta ray swims steadily in a straight line, while further inshore it usually basks or swims idly. Mantas may travel alone or in groups of up to 50. They sometimes associate with other fish species, as well as sea birds and marine mammals. About 27% of their diet is based on filter feeding,[18] and they will migrate to coastlines to hunt varying types of zooplankton such as copepods, mysids, shrimp, euphausiids, decapod larvae, and, on occasion, varying sizes of fish.[19] When foraging, it usually swims slowly around its prey, herding the planktonic creatures into a tight group before speeding through the bunched-up organisms with its mouth open wide.[18] While feeding, the cephalic fins are spread to channel the prey into its mouth and the small particles are sifted from the water by the tissue between the gill arches. As many as 50 individual rays may gather at a single, plankton-rich feeding site.[11] Research published in 2016 proved about 73% of their diet is mesopelagic (deep water) sources including fish. Earlier assumptions about exclusively filter feeding were based on surface observations.[20]

The giant oceanic manta ray sometimes visits a cleaning station on a coral reef, where it adopts a near-stationary position for several minutes while cleaner fish consume bits of loose skin and external parasites. Such visits occur most frequently at high tide.[21] It does not rest on the seabed as do many flat fish, as it needs to swim continuously to channel water over its gills for respiration.[22]

Males become sexually mature when their disc width is about 4 m (13 ft), while females need to be about 5 m (16 ft) wide to breed. When a female is becoming receptive, one or several males may swim along behind her in a “train”. During copulation, one of the males grips the female’s pectoral fin with his teeth and they continue to swim with their ventral surfaces in contact. He inserts his claspers into her cloaca, and these form a tube through which the sperm is pumped. The pair remains coupled for several minutes before going their own way.[23]

The fertilized eggs develop within the female’s oviduct. At first, they are enclosed in an egg case and the developing embryos feed on the yolk. After the egg hatches, the pup remains in the oviduct and receives nourishment from a milky secretion.[24] As it does not have a placental connection with its mother, the pup relies on buccal pumping to obtain oxygen.[25] The brood size is usually one but occasionally two embryos develop simultaneously. The gestation period is thought to be 12–13 months. When fully developed, the pup is 1.4 m (4 ft 7 in) in disc width, weighs 9 kg (20 lb) and resembles an adult. It is expelled from the oviduct, usually near the coast, and it remains in a shallow-water environment for a few years while it grows.[11][24] Females only reproduce every two to three years. Long gestation periods and slow reproduction rates make this species highly vulnerable to shifts in population.

Brain size and intelligence

The oceanic manta has one of the largest brains, weighing up to 200 g (7.1 oz) (five to ten times larger than a whale shark brain). It heats the blood going to its brain and is one of the few animals (land or sea) that might pass the mirror test, seemingly exhibiting self-awareness.[26]

Status and threats

Natural predation

The oceanic manta ray can swim at speeds of up to 24 km/h (15 mph).[27] Because of this speed and its size, it has very few natural predators that could be fatal to it. Only large sharks such as the tiger shark (Galeocerdo cuvier), the great hammerhead shark (Sphyrna mokarran), the bullshark (Carcharhinus leucas), dolphins, the false killer whale (Pseudorca crassidens), and the killer whale (Orcinus orca), are capable of preying on the ray. Nonlethal shark bites are very common occurrences, with a vast majority of adult individuals bearing the scars of at least one attack.[28]

Fishery

The oceanic manta ray is considered to be endangered by the IUCN’s Red List of Endangered Species because its population has decreased drastically over the last twenty years due to overfishing.[29] Because M. birostris feeds in shallow waters, there is a higher risk of them getting caught in fishing equipment, especially in surface drift gillnets and bottom set nets.[30] Whatever the type of fishing (artisanal, targeted or bycatch), the impact on a population which has a low fecundity rate, a long gestation period with mainly a single pup at a time, and a late sexual maturity can only be seriously detrimental to a species that cannot compensate for the losses over several decades.[29]

Since the 1970s,[31] fishing for manta rays has been significantly boosted by the price of their gill rakers on the traditional Chinese medicine market.[32] In Chinese culture, they are the main ingredient in a tonic that is marketed to increase immune system function and blood circulation, though there is no strong evidence that the tonic is actually beneficial to health. For this reason and others, gill rakers are sold at relatively high prices – up to $400 per kilogram – and are sold under the trade name pengyusai.[33][31] In June 2018 the New Zealand Department of Conservation classified the giant oceanic manta ray as “Data Deficient” with the qualifier “Threatened Overseas” under the New Zealand Threat Classification System.[34]

Pollution

There is also the threat of microplastics in the diets of oceanic manta rays. A 2019 study in Indonesia’s Coral Triangle was performed to determine if the filter-feeding megafauna of the area were accidentally ingesting microplastics, which can be eaten by filter-feeders either directly (by ingesting layers of plastic polymers that float on the surface of the water in feeding areas) or indirectly (by eating plankton that previously ate microplastics). The results of the study provided ample evidence that filter feeders, such as oceanic manta rays, that lived in the area were regularly consuming microplastics. Though it was also proven via stool samples that some of the plastic simply passed through the digestive systems of manta rays, the discovery is a concern because microplastics create sinks for persistent organic pollutants like dichloro-diphenyl-trichloroethanes (DDTs) and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs). Manta rays that consume microplastics harboring these pollutants can suffer from a variety of health effects that range from short-term negative effects such as the reduction of bacteria in their guts, or long-term effects including pollutant-induced weakening of the population’s reproductive fitness over future generations, which could negatively affect population levels of the rays in the future.[35]

M. birostris are also victims of bioaccumulation in certain regions. There has been at least one study that has shown how heavy metals such as arsenic, cadmium, and mercury can be introduced to the marine environment via pollution and can travel up the trophic chain. For example, there was a study in Ghana that involved the testing of tissue samples from six M. birostris carcasses; all of them showed evidence of high concentrations of arsenic and mercury (about 0.155–2.321 μg/g and 0.001–0.006 μg/g respectively). While the sample size was not the most ideal, it is a first step towards further understanding the true amount of bioaccumulation that M. birostris undergoes due to human pollution. These high levels of metals can cause harm to the people who consume M. birostris, and could also cause health problems for the M. birostris species itself. More studies need to be done in order to further confirm the negative health effects of bioaccumulation on M. birostris.[36]