Indigenous-led protections spark Bali starling’s recovery in the wild

- An Indonesian songbird once nearly extinct in the wild, the Bali starling, is making a comeback through community-led conservation on Nusa Penida and beyond.

- Strict law enforcement and captive breeding failed to reverse the bird’s decline; poaching and habitat loss continued despite decades of formal protections.

- In the early 2000s, conservationists changed tactics, working with communities on Nusa Penida to establish the island as a sanctuary for Bali starlings.

- Villages embraced traditional awig-awig regulations to protect the starling, creating powerful cultural, social and financial deterrents to poaching.

NUSA PENIDA, Indonesia — Two young conservation workers rattle up on a motorbike and dismount at the edge of a coconut grove. Picking through husks, fallen fronds and stray plastic bottles, they scan the canopy, waiting in stillness.

For nearly 20 minutes, nothing stirs. Then, a flash of white. A Bali starling (Leucopsar rothschildi) pokes its head from the hollow of a dead palm and darts into view before settling on a nearby branch. Moments later its mate follows, the pair taking turns caring for the nest and foraging for food. This natural cavity nest, which sits beside an artificial nest box, is only the second ever recorded on Nusa Penida, a small island off the coast of Bali.

This family of starlings, also known as Bali mynas, are among the world’s rarest birds, endemic to Bali and once reduced to just six individuals in the wild.

Each sighting marks a sign of hope for a species making a cautious comeback through community leadership, cultural tradition and grassroots conservation.

The near collapse of the Bali starling

Songbird-keeping surged across Indonesia in the mid-20th century, driven by migration, rising incomes and competitions that elevated melodious birds as status symbols. The Bali starling, prized for its striking white plumage and distinctive call, became a coveted target for collectors and trappers.

Despite official protections dating back to 1958, weak enforcement across the archipelago allowed a lucrative trade to flourish, fueling an economy of trappers, breeders, trainers and cage sellers. Strict bans have sometimes backfired, making ownership of the illicit birds a mark of prestige among elites, a 2015 study in the journal Oryx reported. At its peak, the caged-bird industry was valued in the trillions of rupiah.

With porous borders, thousands of islands and limited resources, traditional enforcement methods struggled to keep up with massive and global demand. Even when authorities manage to confiscate trafficked birds, they often die in captivity from the trauma, stress and lack of immediate care.

Adding to the starling’s difficulties, land conversion for agriculture, settlements and tourism infrastructure accelerated deforestation and habitat loss, relegating the species to isolated pockets, making it more vulnerable to threats like predation.

The crisis reached its most desperate moment in 2001, when only six known wild individuals remained. Even more dire, this unique species of myna is the only vertebrate endemic to Bali that remains after Dutch hunters shot the last Bali tiger in 1937.

Traditional, top-down conservation achieved limited success

In the mid-1980s, the International Council for Bird Preservation (later BirdLife International) and the Indonesian government formed a coalition that established objectives for monitoring the species, restocking wild populations, establishing breeding programs and raising public awareness. Breeding efforts were successful, but weak oversight and unclear success metrics hindered post-release outcomes, which were poorly monitored, according to an analysis in Biodiversitas.

The Tegal Bunder Breeding Center released 218 birds into Bali Barat National Park (BBNP) over 18 years, but the wild population continued to plummet. Many failed to survive, lingering near release sites, showing continued reliance on humans and becoming easy targets for poachers.

Park rangers increased patrols, yet poaching continued relentlessly in the forest, and 78 birds were stolen from a breeding center in the national park. A pair of birds could command a black market price up to 40 million rupiah in the 1990s (about $4,500 at the time), years’ worth of salary for a park ranger, making it easy to pay off officials if needed.

“The crucial point was that this Western approach had a need to protect, ramp up enforcement, monitor it, and it wasn’t really getting anywhere,” said Paul Jepson, who led the BirdLife Indonesia program in the 1990s. “It wasn’t solving the decline.”

BirdLife donors eventually lost confidence, and the NGO withdrew from the initiative by 1994.

The songbird trade remains a significant source of income for many Indonesian communities, with the caged-bird sector estimated to be worth billions of U.S. dollars. In some communities, a single forest sustains the local economy. Bird-catching is how people put food on the table, send kids to school or pay for health care in an emergency. When less extractive alternatives do not offer clear financial incentive, people resort back to the forest.

“Local communities tend to think and act pragmatically,” said Marison Guciano, founder and executive cirector of FLIGHT, an NGO founded to combat the regional songbird trade. “Meeting basic community needs must be a priority. Conservation efforts are not only about protecting and preserving wildlife and forests, but also building and improving the welfare of local communities.”

Community-led conservation changes the conversation

Conservation on Bali was hampered by weak enforcement, villages scattered across difficult terrain and fragmented habitat for the birds. Coastal trade routes made it easy to smuggle birds, while overlapping laws created loopholes for exploitation. A sustainable Bali starling conservation solution needed adequate land and local support to scale.

Where conventional conservation solutions failed, changing the fate of the wild Bali starling required an unconventional approach. In the early 2000s, Balinese veterinarian and founder of Friends of the National Parks Foundation (FNPF), Dr. Bayu Wirayudha, had such an idea.

“I came up with the idea of, why not make a kind of sanctuary or midway house on an empty island?” Wirayudha said. “Indonesia has more than 17,000 islands, and we only need one.”

The idea faced initial hesitancy from scientists, fearing the move might change biodiversity on other islands, but eventually Nusa Penida was selected as an ideal location for the conservation experiment. It lies immediately off Bali’s southern shore, with a small and manageable landscape and no endangered species likely to be threatened by using the island as an ex-situ conservation site.

Wirayudha began an ambitious mission to meet with every village on the island of Nusa Penida. Representatives from FNPF appeared at communal gatherings like village meetings, ceremonies and weddings to make short speeches advocating the island’s designation as a bird sanctuary and offering reforestation and community development aid. One by one, he collected letters of support. In 2006, all 35 (now 41) traditional villages on the island formally agreed to turn the island into a refuge.

“All the people in our village are working together to secure this species,” said Made Sukadana, chair of an organization working to increase tourism in Tengkudak village. “We plant fruit trees for the Bali starling and support a dedicated, passionate bird person who monitors daily. We are creating interesting activities related to conservation and nature; this brings a positive impact to the villagers’ economy from the visitors.”

FNPF helped villages inscribe bird protection into their customs through awig-awig, Hindu-based customary laws that must be decided upon by the entire community. The mutually agreed-upon rules carry cultural and social weight and promote collective moral responsibility. Violators face steep fines, ceremonies or even the obligation to feed the entire village — penalties more powerful than formal law. Where law enforcement is short-staffed and operates only during working hours, communities can create constant stewardship.

Locals have also become involved in on-the-ground conservation. Villagers help FNPF staff monitor nest cavities and track egg and chick health. Instead of poaching, residents rescue injured birds, plant trees for habitat restoration, distribute saplings, install and monitor artificial nest boxes and manage predators like geckos and monitor lizards.

“You get everyone in your community in a wild bird preserving culture, and it becomes self-regulating,” said Jessica Lee, head of avian species programs and partnerships at Mandai Nature. “These people are paid to patrol forests and protect birds, rather than catching birds to earn an income. They are guardians. They become the eyes and ears on the ground as a community.”

Calling awig-awig the “most important alternative to protect Bali starling,” a 2015 report in the Journal of Bali Studies reported a nearly 1,200% improvement in anti-poaching compliance over formal criminal law on Nusa Penida. Indonesian authorities publicly recognized the success of the ex-situ conservation effort on Nusa Penida for the first time in 2023.

On Nusa Penida, 64 released starlings grew to about 100 by 2009, dispersing naturally and breeding more successfully than in BBNP, some reportedly up to three times per year, thanks to reduced poaching pressure and abundant food. The population still relies heavily on artificial nest sites, but the two natural nests recorded by FNPF are a hopeful sign of self-sustainability.

The sanctuary’s success has attracted publicity and ecotourism, from bird-watcher groups to National Geographic cruise expeditions. Former poachers have become bird guides. Villages have developed shade-grown coffee canopies with bird-watching sites underneath.

The influx of visitors has brought tangible economic gains for residents. Ecotourism revenue has grown, partly driven by interest in the Bali starling. Reports indicate that recovery efforts and tourism development have increased tourist visits, extended stays and improved local incomes.

Awig-awig regulations to protect the Bali starling made their way to mainland Bali when, in 2018, Melinggih Kelod village adopted communal protections for the birds. A string of “Bali starling villages” has also emerged: Tengkudak, Bongan and Sibangkaja. Each has embraced the starling as a source of cultural significance and economic opportunity, integrating habitat protection, agroforestry, certified breeding and tourism opportunities into community life, with support from FNPF.

“In the new commitment on Bali mainland, they put a fine of 10 million rupiah [about $600], not only for Bali starlings, but any bird species,” Wirayudha said. “Second, they must feed the whole community, and if any community members reject their food, this person needs to pay them cash. Plus, make a ceremony to ask forgiveness in the temple. Who would dare do that stupid thing? It will cost them so much.”

In Tengkudak, traditional regulations require residents to plant two trees for each one they cut of species that provide food for the starlings. Population growth efforts have been so effective in Tengkudak that it’s called “Kampung Jalak Bali,” or “The Village of the Bali starling.” Bongan is known for its “Golden Triangle” of conservation, culture and education and houses a dedicated breeding center.

Cautious optimism for a bird coming back from the brink

According to the most recent population survey in October 2021, approximately 420 wild Bali starlings live in BBNP, according to standardized counts conducted by park staff. Another 100 individuals are estimated to live on Nusa Penida.

The recovery is remarkable but still fragile, with success depending on coordination across villages, governments, NGOs and markets. When conservation delivers livelihoods, restored habitats and cultural pride, it builds lasting support for at-risk species. In the case of the Bali starling, community consensus has proven to be one of its most powerful tools for survival.

Banner image: Framed by lush green leaves, a Bali starling sings with its beak wide open, showing off its striking cobalt-blue facial skin and wispy white crest feathers. The surrounding jungle foliage blurs softly, making the bird’s detailed features pop with contrast and texture. Image by Heather Physioc.

Indigenous-led conservation is driving the Bali starling’s recovery from near extinction, succeeding where earlier conventional methods failed. After decades of habitat loss and rampant poaching left only six birds in the wild in 2001, conservationists changed tactics, partnering with Indigenous communities on the island of Nusa Penida. Through the use of traditional customary law, local communities have created a powerful and sustainable sanctuary for the birds.

t Impactful Ninja, we curate positive and impactful news for you. Follow us on Google News or sign up for our free newsletter to get these delivered straight to your inbox—just like our expert roundup below!

The quick summary: The endangered Bali starling is making a significant comeback from near extinction through indigenous-led conservation efforts that combine traditional customs with community protection, growing from just 6 wild birds in 2001 to over 500 today.

One key stat: The Bali starling population has grown from just 6 wild individuals in 2001 to approximately 520 birds today, demonstrating how effective community-led conservation can outperform traditional enforcement approaches.

One key quote: “You get everyone in your community in a wild bird preserving culture, and it becomes self-regulating,” said Jessica Lee, head of avian species programs and partnerships at Mandai Nature.

The big picture: The Bali starling, Indonesia’s rarest endemic bird, is experiencing a remarkable recovery after nearly disappearing from the wild. Once reduced to just six individuals in 2001. This turnaround came after a shift from traditional enforcement-based conservation to community-led protection efforts. By incorporating bird protection into traditional awig-awig laws, communities on Nusa Penida and mainland Bali villages created powerful social and financial incentives that made poaching culturally unacceptable. This approach transformed former poachers into conservation guides and brought economic benefits through ecotourism.

Why is this good news: Indigenous leadership has succeeded where decades of conventional conservation efforts failed, creating a sustainable model for protecting endangered species. The community-based approach established powerful cultural and financial deterrents to poaching that far outperform government enforcement. Villages have embraced the starling as both a cultural symbol and economic opportunity, incorporating habitat protection into daily life. Former poachers now serve as bird guides, while communities benefit from increased ecotourism revenue. The recovery demonstrates that conservation can simultaneously deliver livelihoods, restore habitats, and instill cultural pride while saving species from extinction. What’s next: Conservation groups must continue supporting village-based initiatives that combine economic benefits with protection. More mainland Bali communities need to adopt similar awig-awig regulations to expand the starling’s range. Ongoing monitoring will determine if the birds can become fully self-sustaining, particularly as they begin using natural nest cavities rather than artificial boxes.

Key details of the Bali starling’s recovery:

- A history of decline: Despite legal protection since the 1970s and international captive breeding programs, the wild Bali starling population continued to plummet. Poaching for the illegal caged-bird trade proved impossible to stop with traditional enforcement, and the birds’ value on the black market created a significant deterrent to effective conservation.

- The pivot to community leadership: In the early 2000s, organizations like the Friends of the National Parks Foundation (FNPF) began working with Indigenous communities on Nusa Penida, an island off Bali’s coast. Rather than relying on formal government laws, the initiative centered on traditional wisdom and local empowerment.

- Awig-awig customary law: The recovery’s linchpin is the local awig-awig regulations, which are traditional customary laws. These laws impose severe cultural, social, and financial penalties on poachers, far more effectively deterring illegal activity than formal laws did. A 2015 study in the Journal of Bali Studies noted an almost 1,200% improvement in anti-poaching compliance under awig-awig compared to formal law.

- Economic incentives: Communities have embraced the Bali starling not only for its cultural and spiritual significance but also for its economic benefits. By becoming guardians of the birds, former poachers can now earn income as eco-tourism guides. Villages have also integrated conservation into their economies through certified breeding programs and agroforestry.

- Building a sanctuary: With poaching reduced, captive-bred birds could be safely reintroduced to Nusa Penida. Released starlings have successfully dispersed and bred, leading to a thriving population. As of a 2021 survey, about 100 individuals were estimated to be living on Nusa Penida, supplementing the population in West Bali National Park.

- Continued success and fragile recovery: Inspired by the success on Nusa Penida, some villages on mainland Bali have also adopted similar practices and are now hubs for starling conservation. The species’ recovery is still considered fragile, and its long-term success depends on the continued coordination and commitment of local communities.

over the misty forest of Nusa Penida. Light rain weaves silver threads through the canopy. From the hush of the foliage, a flash of white breaks the green—a bird glides in, landing with effortless precision on a spiny trunk. It’s a striking bird with brilliant white feathers, a deep blue leathery patch around its dark eyes, and black-tipped wings and tail.

Moments later, its companion arrives. They perch facing in opposing directions, luminous against the dark bark and dripping leaves. One raises its crest and sings. The other turns inward, preening damp feathers with a rhythmic calm. These are Bali starlings, among the rarest birds on earth.

Species: Bali Starling

Also Known As: Bali myna, jalak Bali, Rothschild’s mynah

The Bali starling was first described to science in 1912, but fewer than 10 individuals were believed to survive in the wild by 2001, following catastrophic losses from habitat destruction and illegal poaching for the songbird trade. Now, the critically endangered bird is making a comeback from the brink of extinction in the wild, thanks to a combination of conservation approaches. The last 30 years of conservation has included establishing protected lands, market-based approaches, and partnerships with Indigenous communities in Bali and Nusa Penida that established permanent refuges for reintroduction. As a result, the rare and symbolic birds have become critical sources of eco-tourism dollars for many villages.

The Bali starling’s tale is one of incredible recovery. Today, through collective community efforts focused on safeguarding and conserving the species in its natural habitat, the Bali starling is being restored from a captive possession to a creature stewarded by local communities. These communities act as protectors of the bird’s unique cultural and spiritual value, enabling its revival in the wild. As of the most recent population survey in October 2021, there were approximately 420 wild Bali starlings living in Bali Barat National Park, according to standardized counts conducted by park staff, and another approximate 100 individuals are estimated to live on Nusa Penida.

Range & Habitat

- Origin: Endemic to the island of Bali, Indonesia. The Bali starling is the only endemic vertebrate on the island, making it uniquely important to local biodiversity. Balinese culture also reveres the bird’s white plumage as a symbol of purity and a link between the divine and earthly worlds.

- Range: Natural range is extremely limited and restricted primarily to the northwest part of Bali, specifically within the Bali Barat (West Bali) National Park and surrounding areas. Ex-situ conservation populations are being established on Nusa Penida island.

- Habitat: Lowland forests and open woodlands, areas with a mix of savanna, forest edges, shrubland, and grassland

Quick Facts About the Bali Starling

- Order: Passeriformes (perching berds)

- Family: Strunidaae (starlings)

- Genus: Leucopsar

- Species: Leucopsar rothschildi

- Diet: Fruit, seeds, insects, earthworms, nectar, small reptiles

- Height: 9 to 10 inches

- Weight: 2 to 4 ounces

- Lifespan: 5 to 8 years in the wild

- Sexual Maturity: 1 year

- Natural Predators: Snakes, eagles, hawks, lizards

Mating

- Mating System: Monogamous long-term pair bonds

- Mating Season: Bali’s rainy season, November through April

- Courtship Displays: Males raise crest feathers, perform loud calls and bob. Pairs mutually groom feathers.

Reproduction

- Nesting Habits: In tree cavities, often holes excavated by woodpeckers, about 4 to 10 meters off the ground. They line old woodpecker holes or artificial nests with twigs, grass, and leaves

- Broods: 2 to 4 pale blue eggs per clutch, up to 3 broods per season

- Incubation: 12- to 15-day incubation period

- Offspring: Often 1 chick survives per brood

Conservation Status

Critically Endangered

(Last assessed by IUCN 2021)

- Key Threats: The primary threats to the Bali starling’s survival include habitat destruction and poaching for the illegal songbird trade. Poaching drove the Bali starling to near extinction by the mid-1990s, with fewer than 10 individuals left in the wild. Today, an estimated 2 to 4 times more exist in captivity than in the wild.

- Conservation Efforts: Once nearly extinct in the wild, this symbolic songbird is showing promising signs of recovery thanks to a combination of conservation efforts with breeders, local citizens, temple leaders, and communities in Bali and surrounding islands. Conservation efforts focus on protecting and restoring its habitat within Bali, as the species does not naturally disperse to other regions.

Wildlife Snapshot: Bali Starling

The story of the Bali starling is rich with cultural and ecological nuance. See this infographic guide to the Bali starling for a quick digest of the species’ key traits, conservation status, and importance to Balinese culture.

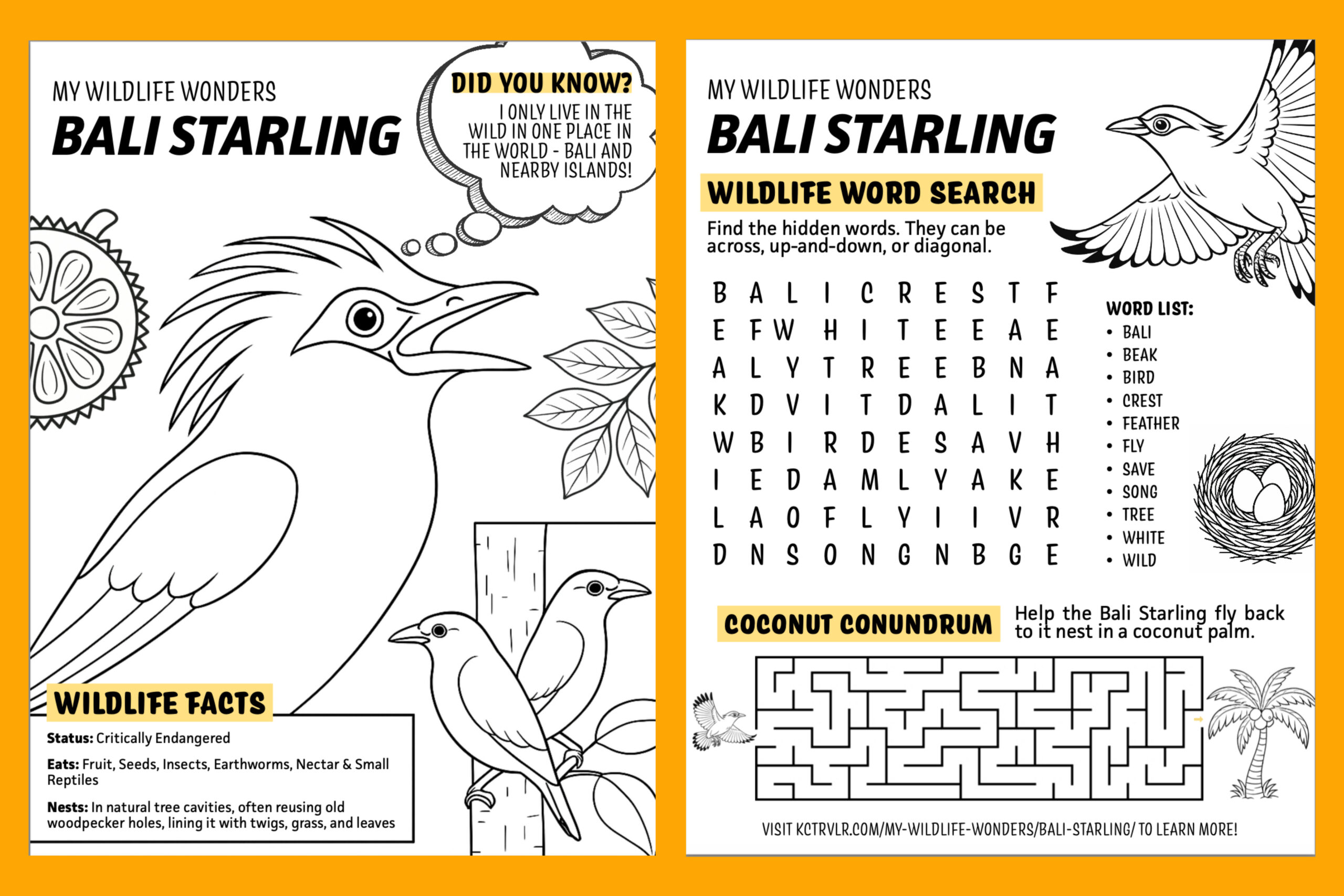

Coloring Sheet & Activities for Kids

Click below to download free, fun activities and coloring sheets for kids to enjoy and learn more about endangered species like the Bali starling!

Printing tip: These pages are designed for 8.5″ x 11″ (Letter) size paper, standard in U.S. printers. Select “Fit to page” (or similar) in your printer dialog menu to ensure all the contents are printed. Choose “Point on Both Sides” or “Print 2-Sided” to reduce paper waste.