App-based transport and delivery workers across India observed a nationwide strike titled “All India Breakdown” on Saturday, February 7, 2026. The strike, led by the Telangana Gig and Platform Workers Union (TGPWU) and supported by several national labor bodies, protested against fare exploitation and falling incomes in the platform transport sector. Ola, Uber and Rapido drivers are going on a 6-hour strike today has been called by the Telangana Gig and Platform Workers Union, also known as TGPWU. The union represents app-based transport workers operating on platforms such as Ola, Uber and Rapido.

Gig workers linked to ride-hailing platforms such as Ola, Uber and Rapido have announced a nationwide strike on Saturday. Drivers plan to remain offline for six hours as part of an action they are calling an ‘All India Breakdown’.

The strike has been called to demand government intervention on minimum fares and tighter rules on the use of private vehicles for commercial rides. The strike has been called by the Telangana Gig and Platform Workers Union, also known as TGPWU. The union represents app-based transport workers operating on platforms such as Ola, Uber and Rapido.

In a social media post shared on Wednesday, the union said app-based transport workers across the country would log out of ride-hailing apps for six hours on February 7 to protest against what it described as unfair pricing practices and weak regulation.

WHY DRIVERS ARE PROTESTING

The union said that aggregator platforms continue to decide fares on their own, even though the Motor Vehicle Aggregator Guidelines, 2025 are already in place. Bengaluru cab driver’s earnings breakdown shows how gig workers struggle brutally

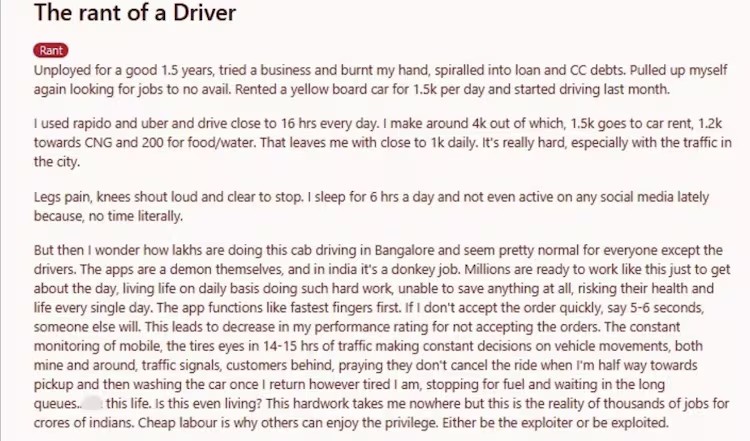

“The rant of a driver,” read the title of the Reddit post shared on r/Bangalore wherein the Bengaluru cab driver detailed his struggle after being unemployed for close to a year and a half.

A Bengaluru cab driver’s rant on Reddit has left social media users discussing the brutal realities of gig work in India.

“The rant of a driver,” read the title of the Reddit post shared on r/Bangalore wherein the man detailed his struggle after being unemployed for close to a year and a half. He wrote that a failed business venture pushed him into loan and credit card debt, forcing him to rent a yellow-board cab and begin driving full-time last month. The driver has rented a car for Rs 1,500 a day and drives nearly 16 hours daily using ride-hailing apps such as Uber and Rapido. Of the roughly Rs 4,000 he earns every day, Rs 1,500 goes towards car rental, Rs 1,200 towards CNG fuel, and about Rs 200 for food and water, leaving him with close to Rs 1,000 in daily earnings.

Extreme physical exhaustion is what he goes through every single day. He sleeps only for six hours in a day and suffers from leg and knee pain due to long hours in traffic. “Is this even living,” he asked, questioning whether such labour leads to any long-term stability or savings. He also criticised ride-hailing platforms, that he said, function on a “fastest fingers first” model. He explained that even a delay of five to six seconds in accepting a ride request could impact his performance rating, while constant monitoring of the phone, traffic stress, fear of ride cancellations, and daily vehicle maintenance added to the pressure. Millions, the driver said, are willing to endure such conditions just to survive day to day, risking their health with little chance of financial security. “Either be the exploiter or be exploited,” he concluded.

In the comments section of the post, several Reddit users expressed empathy and respect for gig workers.

“That sounds like a tough gig. You will get through this. This too shall pass,” one user wrote.

Another commented on the mental resilience required for such work, saying the challenges posed by traffic, poor infrastructure, pedestrians, animals, and confrontations with authorities. “Honestly, I don’t see a way out or situations improving anytime soon,” the user added.

One of the users said that a WagonR driver they spoke to paid Rs 450 a day in rental fees and still managed to earn Rs 3,000–4,000 daily, suggesting that Rs 1,500 per day might be high unless the vehicle is larger.

Others addressed the social implications of the post. “Hope everyone gets to read this. We take people who do these jobs for granted,” a user wrote, while another added, “Life is unfair to the unprivileged and to the privileged who get to hear these stories and can’t do anything. Be kind.” Swiggy, Zomato, other gig delivery workers on New Year’s Eve strike: Key demands already held a nationwide flash strike on December 25, which led to a 50–60% disruption in services in several cities.

Plan New Year Eve better, gig workers from Zomato, Blinkit, Swiggy and other apps are going on strike delivery workers across major platforms including Zomato, Swiggy, Blinkit, Zepto and Amazon are planning a strike on December 31. The strike is being held to highlight growing concerns of workers around low pay, weak job security and safety risks in India’s gig economy.

If you are planning to rely on food delivery or quick commerce apps to ring in the New Year, you may want to plan in advance. Delivery workers associated with major platform companies, including Zomato, Swiggy, Blinkit, Zepto, Amazon and Flipkart, have announced a nationwide strike on Wednesday, ahead of what may be one of the busiest days of the year for online deliveries. The strike is being led by the Telangana Gig and Platform Workers Union (TGPWU), the Indian Federation of App-Based Transport Workers (IFAT) and is backed by multiple regional collectives, including platform worker unions from Maharashtra, Karnataka, Delhi-NCR, West Bengal and parts of Tamil Nadu. Union leaders claim that more than one lakh delivery workers across food delivery, quick commerce and e-commerce platforms are expected to either log out of apps or significantly reduce work on New Year’s Eve.

This planned New Year’s Eve strike is coming just days after a similar protest on Christmas Day, amid the growing unrest within India’s gig workforce. According to the unions the working conditions in the gig economy have continued to deteriorate even as demand for fast deliveries has surged. They claim that the companies are not improving the condition which is just worsening the things for the workers. The strike is said to bring these problems into the light. India Today Tech has reached out to the platform companies, including Zomato, Swiggy and Blinkit, for their comments on the planned strike and the concerns raised by delivery workers. However, we have not received any responses yet.

WHAT SERVICES WILL BE IMPACTED?

New Year’s Eve usually sees record order volumes. Hence, the unions believe the timing of this upcoming strike will force companies to take worker demands seriously.

The disruptions from the strike are expected to impact food orders, grocery deliveries and last-minute shopping of users during year-end celebrations in major cities such as Pune, Bengaluru, Delhi, Hyderabad, Kolkata and Chhatrapati Sambhajinagar, as well as several tier-2 markets.

WHY THE PROTEST?

Unions organising this protest say that the rapid expansion of food delivery and quick commerce has not translated into better pay, job security or safer working conditions for those on the ground. According to union leaders, these platforms continue to prioritise speed and customer convenience while workers bear the brunt of rising workloads and shrinking earnings.

“Our nationwide strike has exposed (referring to the strike that happened on December 25) the reality of India’s gig economy,” said Shaik Salauddin who is founder of TGPWU and national general secretary at IFAT (via The Times of India). He argues that every time delivery workers have raised their voice, these platform companies have responded by blocking their IDs, threats, intimidation with police complaints, and algorithmic punishment. “This is nothing but modern-day exploitation. The gig economy cannot be built on the broken bodies and silenced voices of workers,” says Salauddin.

He also revealed that during the strike on December 25, nearly 40,000 delivery workers participated, which led to around 60 per cent of disruption in deliveries in many cities.

“Instead of addressing workers’ demands, companies tried to break the strike by using third-party delivery agencies, extra incentive bribes, and reactivating inactive IDs,” he added.

Some of the highlighted problems faced by the workers are:

App based governance: One of the main issues highlighted by workers is the increasing reliance on opaque algorithms that govern almost every aspect of work. According to delivery partners, the app-based systems by these companies track their working and decide pay rates, incentives, delivery targets and even penalties, often without explanation or prior notice. Workers claim this lack of transparency makes it difficult to predict daily income and leaves them vulnerable to sudden changes in earnings.

Fast delivery promise pressure: Another major point of contention by the gig workers is the rise of ultra-fast delivery models, including 10-minute delivery promises. Unions argue that these tight timelines are encouraging risky behaviour on roads and significantly increase the chances of accidents. Union representatives say the pressure to meet aggressive deadlines compromises safety and shifts operational risks from companies to individual workers.

“We will not accept unsafe ‘10-minute delivery’ models, arbitrary ID blocking, or denial of dignity and social security. The government must intervene immediately. Regulate platform companies, stop worker victimisation, and ensure fair wages, safety, and social protection,” says a union leader.

The union also highlights that the fast delivery competition between platforms has also resulted in increasingly unrealistic delivery expectations, further putting immense pressure on the workers.

Low income: Another issue is the falling income. According to delivery partners, the company frequently revises their incentive structures, often without clarity, making monthly earnings uncertain. Many workers are also reporting longer working hours just to maintain previous income levels, while still lacking benefits such as paid leave, health coverage or income protection.

Weak grievance redressal mechanisms: Beyond pay and safety, workers have also raised concerns about weak grievance redressal mechanisms. Some of the common complaints by the workers are around the sudden deactivation of work IDs without explanation, delayed or failed payments, penalties for issues beyond their control, and unclear route assignments generated by apps. Workers say there is no effective system to resolve these issues quickly, forcing many to continue working under unfair conditions.

Meanwhile, unions are also demanding basic social security measures for gig workers, including accident insurance, health coverage, rest breaks and pension benefits. They argue that delivery workers play a critical role during festivals, weekends and peak demand periods, yet remain excluded from protections available to formal employees. India’s gig workers are striking. The numbers explain why

Struggling with long shifts and low earnings, delivery workers are demanding change.

Delivery workers from companies such as Amazon, Zomato, Swiggy, Zepto, Blinkit and Flipkart, tired of low wages, lack of safety, job insecurity, and the absence of social protection, announced a nationwide strike on New Year’s Eve. Delivery workers from companies such as Amazon, Zomato, Swiggy, Zepto, Blinkit and Flipkart, tired of low wages, lack of safety, job insecurity, and the absence of social protection, announced a nationwide strike on New Year’s Eve. They previously went on strike on Christmas Day. The strikes have been announced by the Indian Federation of App-Based Transport Workers and the Telangana Gig and Platform Workers Union.

THE PLIGHT OF GIG WORKERS

PAIGAM (People’s Association in Grassroots Action and Movements) and University of Pennsylvania launch first of a kind comprehensive study on working and living conditions of app-based workers in India

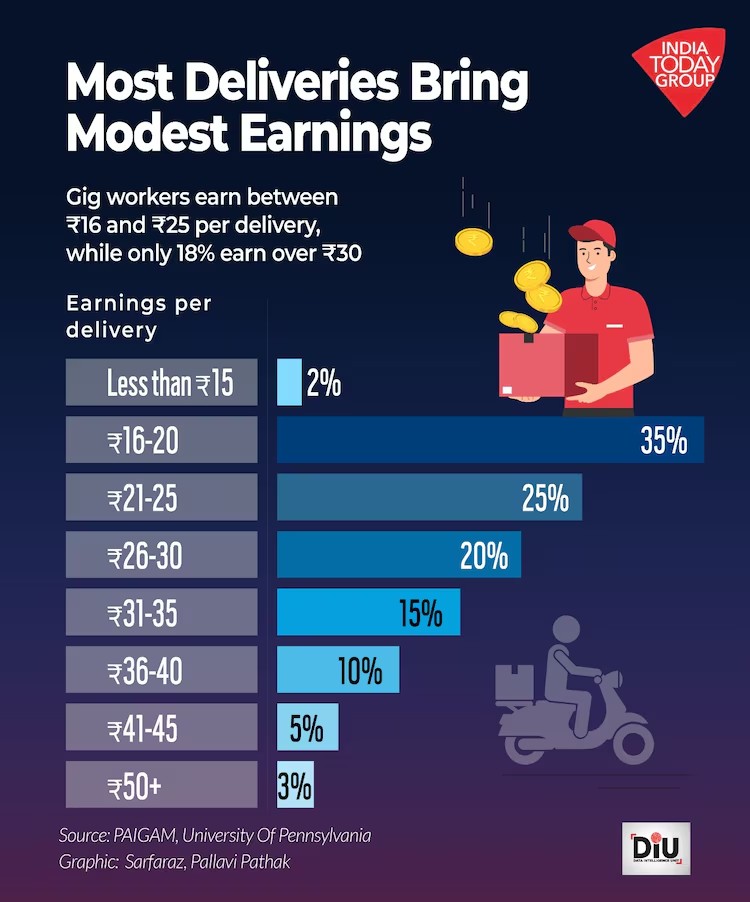

A comprehensive survey of over 10,000 taxi drivers and food delivery workers across eight Indian cities highlights economic, social and psychological costs associated with app-based gig work. Download the report to read more. A fifth of them earned Rs 401–600 a day. About 15 per cent earned Rs 601–800 a day, and only 10 per cent earned between Rs 801 and Rs 1000. A look at delivery workers’ earnings per delivery presents a starker picture. About 35 per cent earned between Rs 16 and Rs 20 per delivery. Another 25 per cent earned Rs 21–25. This means most delivery partners make less than Rs 25 for each order they complete. Only about 10 per cent earn Rs 36–40 per delivery, and a minuscule three per cent earn more than Rs 50 per delivery. Essentially, about 44 per cent earned less than Rs 10,000 a month. A third earned between Rs 10,000 and Rs 15,000. About 20 per cent reached the Rs 15,000–20,000 range, and just five per cent earned between Rs 20,000 and Rs 25,000.

NO LEAVES, LONG HOURS

Time off is a major challenge for gig workers. Nearly half of all delivery partners claimed they did not take holidays. Only about 21 per cent said they were able to take proper time off. The report noted that the “persistent hustle” had adverse effects on the workers’ mental health, contributing to stress, anxiety, and depression.

Waiting time is a major issue. At least half of the delivery partners wait around an hour on average before getting any work. For 43 per cent, this wait stretched up to two hours. Another 35 per cent reported waiting as long as three hours. Some even said they wait four to five hours or more to receive a gig. This waiting time is unpaid. Long stretches of the day pass without any income, forcing workers to stay on the job for long hours.

Most delivery partners are full-time workers with long work hours. Over half of the surveyed workers work 10–12 hours a day, and nearly 20 per cent work 12–14 hours. Only about 25 per cent said they got regular weekly offs; nearly half said they did not get any days off. Consequently, more than a third of the surveyed workers reported leg, foot, and knee pain. About another third reported back pain and related ailments. Some even said they faced serious heart and cholesterol-related issues.

NO SAFETY

Four in ten delivery partners said they faced violence at work. This affects workers directly, with 44 per cent saying it had a negative impact on them. Support from companies is also weak. More than 64 per cent said they received no support from the company. Give drivers of app-based taxi and bike taxi services in the city have announced a nationwide strike on February 7. Drivers of major companies like Ola, Uber, and Rapido will stay off the roads on this day. The “All India Breakdown” refers to a nationwide strike by app-based cab, auto, and bike taxi drivers (Uber, ola, rapido, etc.) on February 7, 2026, protesting low incomes, unfair fares, and lack of government regulation, demanding implementation of the Motor Vehicle Aggregator Guidelines, 2025, for minimum base fares and better working conditions. This coordinated protest, organized by unions like the Telangana Gig and Platform Workers Union (TGPWU), saw drivers log off platforms, causing potential disruptions in major cities. App-based transport workers to observe All-India ‘breakdown’ over falling incomes

App-based transport workers linked to Ola, Uber, Rapido and Porter will observe an All-India “breakdown” on Saturday, protesting falling incomes and alleged exploitation. Unions demand minimum base fares and stricter regulation under the Motor Vehicle Aggregator Guidelines, 2025.

New Delhi: App-based transport workers across the country associated with Ola, Uber, Rapido, Porter and other app-based ride-hailing platforms will observe “breakdown” on Saturday against falling incomes and “worsening exploitation”. They said on Friday that the ‘breakdown’ has been called to protest against falling incomes and ‘worsening exploitation’ due to the failure of governments to notify minimum base fares under the Motor Vehicle Aggregator Guidelines, 2025.

Shaik Salahuddin, TGPWU founder President and IFAT co-founder and National General Secretary, said that despite the guidelines, aggregator companies continue to unilaterally fix fares, pushing workers into unsustainable working conditions.

The key demands of the unions include immediate notification of minimum base fares for app-based transport services in consultation with recognised worker unions, as mandated under the Aggregator Guidelines, 2025.

They are also demanding strict prohibition of private (non-commercial) vehicles being used for commercial passenger and goods transport, or mandatory conversion to commercial category vehicles as per the Motor Vehicles Act and Aggregator Guidelines, 2025.

TGPWU and IFAT have urged the Central and state governments to initiate immediate dialogue with worker representatives and ensure fair, lawful, and sustainable regulation of the app-based transport sector. According to TGPWU founder President, Telangana alone has about 2.5 lakh autorickshaw drivers, 1.5 lakh cab drivers and about 50,000 Porter drivers.

TGPWU had earlier sent a letter to the Union Minister for Road Transport and Highways Nitin Gadkari, Telangana Transport Minister Ponnam Prabhakar and other officials, informing them about the decision to observe All-India ‘breakdown’.

It demanded immediate notification of minimum bus fares by the Central and state government for app-based transport services (autos, cabs, bike taxis, and other aggregator-based services) to be finalised in consultation with recognised driver and worker unions.

Key Issues & Demands:

Platforms set fares unilaterally, leading to low earnings despite long hours. Lack of government regulation is a central grievance for drivers in the app-based transportation industry in India, highlighted during protests such as the recent “All India Breakdown” [1]. Drivers argue that this regulatory gap allows aggregator companies like Uber, Ola, and Rapido to unilaterally set low fares, leading to insufficient incomes and exploitative working conditions [1, 2]. Ola, Uber and other app-based transport drivers’ strike: What are their demands and why are they protesting?

Drivers across India launch a nationwide strike demanding government-regulated minimum fares and better working conditions, citing exploitation by app-based transport companies like Ola and Uber, while commuters face disruptions in major cities App-based transport workers, including drivers and delivery workers associated with major platforms such as Ola, Uber, Rapido, Porter, and other app-based transport services, announced an all-India strike on Saturday (February 7, 2026) to protest falling incomes and increasing exploitation in the platform transport sector. The transport workers also raised their demand for immediate redress regarding panic button installations in the applications. The strike is likely to impact lakhs of commuters in Tier-1, Tier-2, and metro cities across the country.

Who is leading the strike?

The protest call was given by Telangana Gig and Platform Workers Union (TGPWU) and Indian Federation of App-based Transport Workers (IFAT), involving thousands of drivers employed in cab-hailing and quick-delivery platforms.

Speaking to PTI, Keshav Kshirsagar, head of Maharashtra Kamgar Sabha, said the strike began across Maharashtra and other parts of the country in the morning. Most autorickshaw and taxi drivers have supported the strike, Mr. Kshirsagar said. Karnataka App-based Workers Union (KAWU), which too announced its participation in the All-India strike, had written to Union Minister of Road Transport and Highways Nitin Gadkari and State Transport Minister Ramalinga Reddy to immediately notify minimum base fares for app-based transport services, and to prohibit usage of non-commercial vehicles for commercial transport. “Without regulated base fares for transport services, aggregator companies can unilaterally set fare prices, and riders and drivers are left in precarious, unstable, and exploitative working conditions. This includes, but is not limited to, workers on platforms such as Ola, Uber, Porter, and Rapido,” the union’s letter notes.

What are the demands?

President of TGPWU and co-founder national general secretary of IFAT Shaik Salauddin said the protest is to demand Central and State Government-notified minimum base fares for Ola, Uber, Rapido and other aggregators such as autos, cabs and bike taxis-set with driver unions. This is pushing millions of app-based drivers into poverty while aggregators continue to draw the profit.

Addressing a letter to Union Minister of Road Transport and Highways, Nitin Gadkari, IFAT and TGPWU pressed the demand for government-notified minimum base fares for app-based transport services. “In the absence of government-regulated fare structures, aggregator companies continue to unilaterally fix fares, leading to severe income security, exploitation, and unsuitable working conditions for millions of transport workers. The Motor Vehicle Aggregator Guidelines, 2025, clearly mandate regulatory oversight, fare transparency, and protection of driver livelihoods, which must be effectively implemented through enforceable Central and State-level notifications,” the letter noted. Mr. Salauddin said, despite implementation of Motor Vehicle Aggregator Guidelines, 2025, platforms continue to fix prices arbitrarily. “Therefore, we press two demands before State and Central Governments. This includes notification of minimum base fares and end of private vehicles for commercial rides,” he added. “We have a list of demands that we want to submit to Union Minister Nitin Gadkari. There should be a Rashtriya Chalak Ayog for the welfare of drivers, private bike taxis should be banned immediately across the country, and surge pricing on app-based platforms should be addressed, as the drivers do not get any benefit out of it, but people think drivers are making money,” said Kishan Verma, president of All Delhi Auto Taxi Congress Union.

Strike’s impact

Although the union claimed that drivers have kept their vehicles off the roads, taxis and autorickshaws have been available in Maharashtra for booking on app-based platforms of major companies, including Uber, Ola and Rapido, since the early hours of the day. The Maharashtra Kamgar Sabha had earlier said that the strike was aimed at opposing the “arbitrary” fare policies of ride aggregators, seeking strict enforcement against “illegal” bike taxi operations that were affecting the livelihoods of licensed cab and autorickshaw drivers.

Similarly, in Delhi, a delegation of transport and delivery gig workers met the Leader of Opposition (LoP) in the Lok Sabha Rahul Gandhi to discuss the need for legislation from the Centre and implementations of regulations in Congress-ruled States.

“While there are 140 panic button device providers approved by the Central Government, the State Government has declared nearly 70% of these companies unauthorised. As a result, cab drivers are being forced to remove previously installed devices and spend approximately ₹12,000 unnecessarily to install new devices, causing severe financial hardship,” the statement said.

The drivers’ body also raised concerns over loss of income due to an increase in the number of autorickshaws under the open permit policy, and also alleged that victims of accidents involving illegal bike taxis are denied insurance benefits.

Key aspects of the issue include:

- Fare Determination: Drivers lack input on fare structures, which they claim are often below operational costs [1, 2]. They demand the government enforce minimum base fares to ensure fair earnings [1].

- Working Conditions: The absence of regulations means drivers often work long hours with little job security or benefits [1].

- Enforcement of Guidelines: A key demand of unions like the Telangana Gig and Platform Workers Union (TGPWU) is the mandatory implementation of the Motor Vehicle Aggregator Guidelines (MVAG), 2025, issued by the Ministry of Road Transport and Highways [1, 3, 4].

As the EV race intensifies, Ola Electric’s new policy, backed by AI and customer-centric innovation, is expected to play a pivotal role in boosting adoption, satisfaction, and trust in electric mobility. It is a 65-minute drive from Rajiv Chowk. This development marks a significant milestone for LML as it solidifies its commitment to expanding the company’s operations and promoting sustainable mobility solutions in India.

The newly acquired land will serve as the foundation for LML’s state-of-the-art EV industrial park. This park aims to revolutionize the EV manufacturing landscape by combining cutting-edge technology, innovation, and sustainable practices under one roof. The industrial park will be specifically dedicated to its upcoming LML’s e-scooters.

In early 2022, the company entered into a strategic partnership with Saera Electric Auto, the former manufacturing partner of Harley Davidson in India to produce its electric two-wheelers and the production has been successfully taking place at the facility. However, the recent development will enable the brand to foster collaboration and growth within the EV ecosystem. With this progress, we aim to accelerate the adoption of electric mobility in India while fostering partnerships with like-minded organizations.”

This facility will have a well-equipped skill development centre for training local youth in EV technology. Trainees would be absorbed in LML as per merit.

Commenting on the same, Dhirendra Khadgata, Deputy Commissioner Nuh Haryana said, “We congratulate LML on this remarkable accomplishment! This Electric Vehicle Industrial Park in our state will benefit our region in an economic and environmental sense and create numerous employment opportunities for skilled workers. We are looking forward to working with LML to complement our goal of a greener and more developed technology future.”

LML will invite ancillary unit partners and other potential partners to join them on this transformative journey. The park will provide a conducive environment for these partners to establish their component manufacturing units, enabling them to contribute to the production and advancement of LML’s upcoming e-vehicle.

By establishing the EV industrial park in Haryana, LML aims to leverage the region’s rich talent pool and robust infrastructure to create a hub for sustainable mobility solutions. This strategic location will enable LML to streamline its operations, optimize supply chains, and further enhance the efficiency of its manufacturing processes.

As the EV race intensifies, Ola Electric’s new policy, backed by AI and customer-centric innovation, is expected to play a pivotal role in boosting adoption, satisfaction, and trust in electric mobility.

In a bold move to revolutionize the buying process has announced a new policy dubbed #Hyper delivery, designed to transform how customers receive their vehicles. The company’s latest innovation combines artificial intelligence, automation, and same-day service to streamline and speed up vehicle registration and delivery, much like the quick-commerce models in retail.

With the official #HyperDelivery launch, Ola Electric is now offering a same-day registration and delivery service, allowing customers to ride home on a fully registered electric scooter within hours of purchase. This applies whether the purchase is made online or at a physical Ola Electric Store. The company says it has eliminated the traditional hurdles—middlemen, manual paperwork, and days of waiting—through advanced automation systems and backend integration with transport authorities.

This electric vehicle delivery policy is expected to set a new benchmark in the Indian automobile sector, offering unmatched convenience, especially to the tech-savvy generation seeking instant gratification.

“This industry-first purchase and delivery transformation has been made possible due to the company’s strategic decision to leverage AI for automation and moving its vehicle registration process in-house. By integrating these critical steps into its operations, the company has enabled a much smoother and efficient journey from purchase to delivery, thereby enhancing customer experience,” the company added.

How #HyperDelivery Works

The cornerstone of the new policy is Ola’s AI-powered backend, which automates the entire vehicle registration process. Once a customer confirms their order, the system swiftly handles documentation, verification, and registration in coordination with regional transport offices (RTOs). This cuts down the standard multi-day process to just a few hours, delivering on the promise of “order today, ride today.”

Key #HyperDelivery Benefits

● Same-day vehicle delivery and registration

● Fully online or offline purchase flexibility

● Zero dependency on middlemen or agents

● Seamless experience powered by AI automation

● Reduced paperwork and manual intervention

Upon completion, the factory will create almost 10,000 jobs. It will initially have an annual capacity of 2 million units. It would showcase India’s skill and talent to produce world-class products that would cater to global markets.

Aggarwal said, “This is a significant milestone for Ola and a proud moment for our country as we rapidly progress towards realising our vision of moving to sustainable mobility solutions across shared and owned mobility”.

Ola’s factory will serve customers not only in India but in markets the world over, including Europe, Asia, and Latin America.

The move has placed Ola in direct competition with legacy electric two-wheeler makers, such as Ather Energy, Hero Electric, and TVS Motor Company. It would catalyse the reduction of India’s import dependence in a key future sector like EVs, boost local manufacturing, create jobs, and improve technical expertise in the country.

According to Ola, the factory will also galvanise India’s EV ecosystem and establish the country as a key player in the EV manufacturing space. The factory will produce Ola’s upcoming line of two-wheelers, starting with Ola’s e-scooter. It features many firsts, including seamless design and a unique removable banana battery that is easy to carry and can be charged anywhere. It is also equipped with intelligent software that elevates the entire consumer experience of owning a scooter. Ola plans to bring many such design and software innovations to its entire two-wheeler product portfolio. Both parties haven’t disclosed the size of the deal yet, however, several media reports claimed that Etergo was valued in between $80-85 million last year.

Founded in 2014, Etergo has developed an all-electric state-of-the-art AppScooter and uses swappable high energy density batteries to deliver a range of up to 240 km.

Ola Electric ran several pilots to deploy electric vehicles and charging solutions across a few cities with a focus on 2 and 3 wheelers. Besides traditional scooter manufacturers, Ather Energy is a prominent electric scooter manufacturer in the country.

Meanwhile, Ola Electric two-wheeler play will likely compete with scooter rental companies such as Bounce. It’s worth noting that Ola also invested in Vogo that competes directly with B Capital-led firm.

Sources revels, every Friday, Bhavish Aggarwal, spends quiet a good amount of time at a site , rings in the weekend at a 500-acre site in Krishnagiri, Tamil Nadu, amidst rocky surfaces and sounds of the ground being dug up by JCB trucks by supervising the construction work and conducting reviews to ensure his ambitious to come true.

The Ola FutureFactory in Krishnagiri the largest electric two-wheeler plant in the world, with an annual capacity of 10 million units. The 10 production lines at full capacity are expected to crank out 1 scooter every 2 seconds at full capacity. It is investing Rs 2,400 crore in the plant and will create 10,000 jobs.

Expected to finish phase 1 in June this year, it will have a capacity of two million units a year. We will have 15 percent of the world’s manufacturing capacity. Everyone is working day and night to make it happen.

We believe we have an opportunity to put India on the world map. That is the reason why we are building a mega factory. By responding on the question on how we will find demand- this will happen if we build the right products. Our first product will be a couple of generations ahead of anything built in the market. With products, cost, and scale, you can enable mass adoption,” he said.

In terms of per-capita ownership of two-wheelers per 1,000 people, India’s numbers hover around 160 compared to Vietnam which has 600. So, India can get to 500-600, Aggarwal said.

Bhavesh revels, we are building our own battery packs. We are building our own design, we’re designing engineering and manufacturing our own battery packs for designing, engineering, and manufacturing our own motors. And we’ll also make all software. So it’s a much more vertically integrated technology,” Aggarwal said.

Ola Electric had acquired Amsterdam-based electric manufacturer Etergo in May last year, with plans to launch two-wheelers globally. It has been running pilots to deploy electric vehicles (EVs) and charging solutions across cities.

By responding to the sales and distribution network, as part of its distribution, Ola is also planning to build a D2C (direct-to-consumer) channel, on top of its cab-hailing app.

When asked about the competitive environment and the entry of Tesla, Aggarwal said, “When an iconic company like Tesla is looking to enter India, it will be a massive positive for the whole ecosystem. It will catalyse it, from demand to suppliers to other automotive companies. It is all the better for companies like us and also for consumers in the end.” App-based workers call for a nationwide strike on Feb 7 over minimum fares among its demands, the Union said the fare structure should be finalised in consultation with recognised driver and worker unions the union has also demanded a ban on the use of private, non-commercial vehicles for passenger and goods transport Telangana Gig and Platform Workers Union (TGPWU), in coordination with national labour organisations, has called for a nationwide strike by app-based transport workers on February 7.

The Union is demanding government-notified minimum base fares and action against the use of private vehicles for commercial rides. The union said drivers of autos, cabs and bike taxis operating on platforms such as Ola, Uber, Rapido, Porter and other aggregators will observe an “All India Breakdown”.

In a letter addressed to the Union Road Transport Ministry and the Telangana government, the Union said app-based transport workers across India face income insecurity due to the absence of regulated fares.

The letter said this has resulted in “severe income insecurity, exploitation and unsustainable working conditions for app-based drivers and riders.”

The Union cited the Motor Vehicle Aggregator Guidelines, 2025, which mandate regulatory oversight, fare transparency and protection of driver livelihoods. These must be effectively implemented through enforceable Central and State-level notifications, the letter noted. Among its demands, the Union said the fare structure should be finalised in consultation with recognised driver and worker unions.

The Union has also demanded a ban on the use of private, non-commercial vehicles for passenger and goods transport.

Alternatively, it said such vehicles should be mandatorily converted into commercial category vehicles in line with existing laws.

Shaik Salauddin, founder president of the TGPWU, said the protest aims to push governments to enforce existing rules. “Government silence has enabled platform companies to continue unchecked,” he added.

The February 7 strike follows a nationwide protest by platform-based workers on December 31 under the banner of the Indian Federation of App-Based Transport Workers.

Platform-based workers from companies such as Swiggy, Zomato, Zepto and Amazon participated in that protest, raising demands related to pay and regulation, the removal of the 10-minute delivery model and the blocking of workers’ IDs without transparency.

Unions said the February action reflects growing mobilisation among app-based transport workers across India.

The MVAG 2025 aims to address these issues by proposing:

Measures for driver welfare and working conditions [1, 3].

Mandatory minimum base fares [1].

A maximum surge price limit [3].

Ride-hailing services across India may hit a speed bump on February 7 as drivers associated with Ola, Uber and Rapido call for a nationwide strike.

Drivers are demanding government-notified minimum base fares, a ban on the commercial use of private vehicles, the removal of rules allowing fares to be set up to 50% below base rates, and legally binding protections for their income and working conditions.

The Moral Economy of Platform Work

1 Introduction

In December 2018, a video of a Zomato food-delivery man from India surfaced on Twitter and went viral. In this video recorded by a customer, the food-delivery person was standing below her apartment and seemed to be eating food from what looked like a restaurant package or container. He then opened another container and ate something from it as well before he proceeded upstairs to deliver the woman’s food. The video went viral very quickly on social media platforms and generated a range of responses from social media users. Some people responding to the video on Twitter expressed anger and outrage against the food-delivery platform, and others started making jokes and memes about the incident. Many users shared their own stories describing similar experiences, in which they had received half-eaten food, sometimes with photographs and videos of food-delivery workers taking a sip of a milkshake or grabbing a few chips from what looked like a customer’s order. Reporting on the viral outrage, an opinion piece in India Today, a leading news portal, exclaimed, ‘Yuck! Video of Zomato guy eating food before delivery shows food apps have a problem!’ The author continued:

Yuck! Think again. It’s just one person who has been caught doing it on video. But there are thousands of delivery guys working with apps like Swiggy, Uber Eats, Zomato, FoodPanda and others and what if there are many more such delivery guys, who like to take a bite out of the food they are delivering.1

As the outrage on Twitter continued, Zomato and Swiggy, the leading platform companies in India, both issued statements through their official social media accounts, reassuring customers that they take ‘food tampering’ very seriously and that this incident would not be forgiven or forgotten. Within a day of the incident, the worker was identified and subsequently suspended, and new guidelines for training and dealing with unprofessionalism were publicly issued. Zomato even announced the development of ‘tamper-proof packaging tape’ to ensure that such incidents would never happen again.

After the initial outrage subsided, the pendulum swung in the other direction, and the online discourse moved to discussions in which users expressed feeling bad for the suspended worker. Some questioned whether it could be proven that the worker was not eating his own food, rather than food ordered by a customer. They challenged the elitist mentality of the customer and social media users who assumed that the worker could not have ordered restaurant food himself while on the job. Others tweeted, pointing to the structural exploitation inherent in the design of gig economy platforms, such that platform workers could not even afford to take a lunch or restroom break during the day. Increasingly, a consensus formed that it was morally unjustifiable to record an obviously less privileged worker, with some even wondering what might be so wrong or offensive about a hungry worker eating some food that it merited a suspension. Yes, it was wrong and inappropriate for a worker to eat from the delivery order but, given the circumstances in which platform workers operate, could one mistake not be forgiven? As some customers/users reasoned, after all, platforms or customers were also regularly caught and exposed for mistreating Uber drivers and food-delivery workers in several ways (suspension, violence, altercations, unfair ratings). Yet others chimed in, advising fellow customers/users to be considerate and to offer their delivery workers water, biscuits, and snacks so that they (the workers) would not have to take from customers’ orders.

At the time of writing this article, this incident is probably the most widely known but certainly only one in a regular stream of news items about episodes of friction and negotiation between platform workers, customers, and companies.

The ‘gig economy’, sometimes also erroneously called the ‘sharing economy’ (Botsman & Rogers 2010) – typified by early ride-hailing ventures such as Uber, Ola (in India), and Didi Chuxing (in China) – is at least a decade old. Since the early days, 2008, when Airbnb was founded, and 2009, when Uber emerged,2 the gig economy has grown enormously and encompasses a wide range of daily services, such as plumbing and carpentry, beauty and wellness services, house cleaning and domestic chores, which are now offered and paid for with smartphone apps. It would not be an exaggeration to say that what has proliferated with the growth of these platforms is also the ‘logic of the gig’ – the transformation of a variety of urban infrastructural services and businesses into real-time, on-demand app-based services provided through the aggregation of a temporary workforce. This logic of the gig has gone beyond the gig economy and consumer service platforms to ‘disrupt’ the management of work and workers in other service and manufacturing industries as well.

The introduction to this special issue on ‘Digital Platforms in Contemporary India: Transformation of Quotidian Life Worlds’ focuses on the ways in which everyday interactions in contemporary India have changed since the arrival of digital platforms. The proliferation of gig-work platforms in India offers multiple points for consideration with regard to the new configurations that might emerge from the entanglement of the digital with the sociocultural in the Indian context. The most prominent and widely discussed development is the transformation of labour in the aftermath of the gig economy, both globally and in India. However, platformization has created far-reaching effects beyond changing how people work. Gig platforms rely on internet connectivity, roads, sidewalks, digital literacy, and access to technology, among other kinds of infrastructure. In addition, ‘gig logic’ has piggybacked on the social stratification of caste, class, gender, and, hence, labour. These sociocultural orders have long guided understandings and norms of informal work and the social treatment and position of domestic workers as well as ‘menial workers’. Against this backdrop, the visible reality of workers’ rights, compensation, and the algorithmic opacity that enables their exploitation – the ‘reality of gig work’, as we might call it – is undergirded and sustained by the other socioeconomic, political, and cultural realities of migrant work, caste and religious oppression, the demographic and labour composition of cities, and so forth. Therefore, we suggest that globally, platform work must be studied in conjunction with people’s life projects because these dynamic projects proceed amid material and sociopolitical realities.

Our motivation in calling for a broader and deeper analysis of platforms, which are shaped by and shape urban life, is to facilitate a rapprochement enabling us to study play, work, social relationships, cultural values, and norms as dimensions of platformization that are equally important and interesting. Our choice of a moral economy framework is a step in that direction, because it transcends the predominantly economic view of labour in gig studies, so that we can also examine consumers of gig platforms and what happens between people in the gig economy on a daily basis. The broader goal of this article is to emphasize the quotidian as a rich site for understanding digital and social transformations. In the following sections, we first offer some background on the size and scale of the gig economy as well as a relevant scholarly analysis that identifies its social and economic impact. Then we present ethnographic data from our fieldwork to discuss some key themes that illuminate the moral economy of gig platforms and the role played by dynamic moral norms in the functioning of the platform economy.

2 Method/ology

The article is the result of conversations and reflections between the authors that began in 2018. At the time, the first author was a co-principal investigator (co-PI), and the second author one of four research fellows on the Mapping Digital Labour Project in India for the Centre for Internet and Society, Bangalore. The reflections presented here draw on our long-term research and iterative analysis as we conducted individual and collaborative fieldwork in India between 2016 and 2020. As a result, the article draws on at least four different qualitative research inquiries involving platform work in ride hailing, food delivery, and beauty and wellness services in Bengaluru/Bangalore, Delhi, and Mumbai. We draw on semi-structured interviews with gig workers as well as participant and marginal observations at the sites of work, training, and rest, such as parking lots, malls, small shops along the pavement where workers eat and drink tea or coffee, as well as warehouses and back offices of platform companies at which gig workers are trained. In addition to our interviews and observations, the article draws on two short surveys (n = 105 responses) conducted by the first author with gig workers in Bengaluru. The survey responses are not intended to produce generalizable findings but are indicative that the feelings and moral responses that emerged at certain moments were certainly shared by more than a handful of gig workers. These surveys were administered online and offline in Hindi, English, and Kannada and included questions about workers’ identity, demographic information, the platforms for which they worked, when they started work, and open-ended questions about their daily work on platforms.

3 Introduction to the Platform Economy in India

Gig economy platforms in India offer a variety of urban services through smartphone apps: local travel, domestic work, food delivery, beauty and wellness, and so on. It is estimated that at least USD 50 billion per year is earned by digital labour platforms (Heeks 2019), including those for ride hailing, food delivery, personal services, and digital content creation. The global South alone has approximately 40 million platform workers, about 1.5 percent of the total global workforce (Heeks 2018). Some estimates suggest that as of 2018, approximately 3 million people are employed in gig work in India (Banik & Padalkar 2021), and that number was expected to exceed 6 million at the end of 2021.

Two important global trends have shaped the story of platforms, especially platform work. First, in different ways, under and unemployment is a global problem (Heeks et al. 2020). This problem is only going to grow because it is estimated that, in 2022, India will add about 350 million people (Saini 2015) to an existing work force of 470 million (PTI 2014). Given that countries in South and Southeast Asia are the world hubs for migrant labour, such a shift in workforce demographics has substantial implications for domestic, regional, and international labour markets. The second important trend is the increased connectivity that has made something like technologically mediated real-time matching of demand and supply possible globally. As the International Telecommunication Union (ITU) reported, within a decade (2003–2013), those with access to overall internet connectivity in all forms rose from 15 percent of the world’s population to over 40 percent. In India, the emergence of platforms also coincided with the ‘Jio explosion’. Reliance Jio is a telecom network launched in 2015 by Reliance Infocomm., its parent company, with an initial investment of about USD 42 billion, and its services are distributed through a network of more than 150,000 small electronic retailers (Mukherjee 2019). Both these trends indicate that app-based platform work as well as other forms of digital labour, such as crowdwork for services such as Amazon’s Mechanical Turk, have become accessible and attractive opportunities especially for a growing workforce in India.

Scholarship on gig work as digital labour in the global South, including in India, has grown. In a series of studies on crowd-based work as well as work via app-based platforms (Anwar & Graham 2021; Graham & Anwar 2019; Graham et al. 2019; van Doorn et al. 2020), Oxford-based researchers have reported on the state of digital labour in sub-Saharan Africa, Southeast Asia, and South Africa. One of the key insights offered by these researchers is the creation and availability of a ‘global labour market’ (Graham & Anwar 2019) now and its effect on social and economic mobility in these regions in the Global South. The loosening of local labour markets they describe is something that we also observed in Bengaluru and other parts of India. Before digital platforms became available, job search, job discovery, communication about work, and managing expectations about work and payment all depended on familiarity with the local linguistic, ethnic, and regional dynamics, creating reliance on personal networks. This meant that for newcomers especially those from North India but also others with non-Kannada and non-South Indian linguistic and cultural backgrounds, finding blue-collar work and being hired to do it was a constant challenge before app-based work became available to them. Prabhat et al. (2019) argue that, in a country such as India, with an ‘exploding demography’, widespread unemployment and a systemic lack of labour contract enforcement, Uber and ride hailing in general are driving micro-entrepreneurship by offering migrants from smaller towns to cities the opportunity to become small business owners. Ahmed et al. (2016) in their study of app-based auto-rickshaw (a popular three-wheeler vehicle) drivers in Bengaluru highlight that the Ola app did not change the inherent vulnerability of rickshaw driving in cities. Surie and Koduganti (2016) show that app-based work enables new rural migrants to accumulate short-term wealth in Bengaluru despite receiving minimal welfare benefits. App-based ride hailing and food delivery offer youth from rural Karnataka immediate and accessible work at a time of prolonged drought and agrarian distress (Surie & Sharma 2019). In an article on app-based beauty and wellness workers in Bengaluru, Raval and Pal (2019) study how workers use the formal features, design, and infrastructure of the app to carve out a professional identity and establish themselves as dignified professionals. At a broader level, Athique and Parthasarathi (2020: 4) suggest that platform capitalism in India has expanded the ‘frontiers of the formal economy and meditating its integration with the informal economy and thereby affecting a greater intimacy with everyday life’. The changes brought about by platformization have uneven effects in the short and long term, so gig workers, as we demonstrate, have to develop and rely on their own judgment and feelings to balance what is good for them versus what is expected of them while operating with a great deal of uncertainty.3 Our article adds to the scholarship on this ongoing process of enmeshment, or intimacy between algorithmic platforms and formal and informal economies, in India and the kinds of socio-moral questions it raises for different actors in the gig economy.

4 Platform Work and Life

Critics, activists, and platform scholars have argued that gig work is not really as flexible as platform companies portray. The global rise of the gig economy has been attributed to the ongoing casualization and flexibilization of labour. So, many scholars locate platforms and platformization along the continuum of the post-Fordist reorganization of labour practices. Platform labour has been studied for its impact on the otherwise declining or stagnant national wages, for the long hours and physically laborious and mentally taxing ‘menial’ work (Aloisi 2019; De Groen et al. 2018). Many critics of platform work emphasize the lack of enforcement of minimum wages (Collier et al. 2017; Jarrahi et al. 2020). As they argue, platforms resort to deliberate misclassification of platform workers as contractors rather than employees in order to avoid giving employment benefits or paying a minimum wage. These features of platform work contribute to the ongoing erosion of social protections. These issues along with the creation and maintenance of information asymmetry through ‘algorithmic blackboxing’ or the strategies used by platform companies to evade scrutiny of their technological interventions certainly establish that platform companies, and platform capitalism broadly, is propagated through extractive practices, creating a ‘reserve force’ of gig workers who are always ‘switched on’ and ready to work but are also duly or sustainably compensated for the amount of their work, risk-taking, and service quality.

Although debates on reclassifying gig workers as full-time employees continue with some success, mostly in Europe and the UK, in the majority of the world, especially in the global South, platform companies and gig work have emerged as nonstandard yet massive employers at a time when many countries are also facing youth unemployment crises. The other important socio-material factor that deserves greater consideration in a study of the impact of platformization is that standard or formal, office-based white-collar employment is restricted or unattainable for many people, including low-skilled migrants, people who are undocumented, single mothers, and people with primary caregiver duties.

What have these changes in the labor market meant in terms of the sociocultural and moral aspects of work? Scholars have answered this question by looking at the moral dilemmas and calculations that platforms create for workers as well as customers and platforms. Based on ethnographic fieldwork in Philadelphia, Shapiro (2018) illustrates that platform workers engage in ‘qualculation’. Qualculation involves rational calculations and qualitatively and affectively based judgements, which rely on an understanding of the obligations between the worker and the company. Similarly, Chen and Sun (2020) identify moral dilemmas in the time-pressed work of food delivery in China because workers are compelled to run red lights. Their work also reveals that workers’ estimates of time conflict with algorithmic estimates of the time needed. We continue this drift towards quotidian and unfinished work here. Sheshtakofsky and Kelkar (2020) argue that, for platforms to operate, companies rely on ‘relationship labour’, which maintains customer-platform relations. In their comparison of the organizational structure at two Silicon Valley start-ups, they show that platform companies use agents in roles such as account management and community management. Going beyond organizational structure to look at the wider social norms with which platforms might come into conflict, Lalvani (2021) examines food-delivery platforms’ services as answering the question of ‘what to eat next’ within the long context of domestic labour and cooks hired by households. Food-delivery apps offer customers a wide choice in terms of food, but algorithmic matching replaces customers’ hiring practices that make calculations based on gender, caste, religion and region of workers to ensure compliance to norms of feeding and being fed and minimise perceived threat to the household.

By offering food, platforms aid in the biological reproduction of customers, but they also threaten the social reproduction of the norms of feeding and being fed. We go further in this direction by examining the relationship between changes at work and changes in social life.

5 Processual Understanding of Platforms

Another important yet implicit goal of this article is to encourage scholars of platforms to adopt a processual perspective that will explore the iterative design changes in platforms and related policy changes as well as the ongoing adoption, rejection, and heterogenous use of platforms. This epistemic and ontological dynamism of media objects such as platforms has deep relevance not only to the moral stances that gig workers and others take but also informs how quickly people change their minds about what is appropriate or called for by a situation.

As scholars studying platforms in situ (Kumar 2020; Mazumdar 2020; Qadri 2021) have noted, algorithmic platforms contribute to a transformation in urban materialities and socialities as they continue to rework and produce new considerations and subsequently revised norms in our interactions with public transportation, understanding of gratitude, timeliness, safety, help, and, ultimately, value. Gig platforms shape and are shaped by their urban environments through altering the temporal and corporeal rhythms of cities as well as the flow of transport, labour, and biopower (urban reproductive capacity), among other things. Although most platform services are available for only a limited period every day, the ‘new normal’ service established by app companies has stretched and reconfigured the temporal assumptions and possibilities that undergird the urban experience: when (it is possible) to eat, how or when to make time for personal grooming, and how late a person (woman) can afford to stay out or travel in the city.

Studies have also shown platforms’ social and economic impact through examinations of mutual aid networks that sustain platform work. Reporting from the Philippines, Soriano and Cabañes (2020: 2) offer ‘entrepreneurial solidarities’ as a framework for explaining the solidarity forged by gig workers. This solidarity, they explain, is ‘characterized by competing discourses of ambiguity, precarity, opportunity, and adaptation … articulated and visualized through ambient socialities’. Far from a simple, passive acceptance of neoliberal discourses around digital labour (as flexible, empowering, and ‘the future of work’), the Filipino gig workers’ cooperation contributes to their ability to push for structural changes but also, at times, undermines their potential for resistance as a group. Duffy et al. (2019: 2) view the ‘penetration of economic, governmental and infrastructural extensions of digital platforms’ as a process at an institutional and everyday level. This processual nature is evident if one considers the response of platforms to challenges. In the early years of ride-hailing services, especially after a female passenger in New Delhi in 2017 was raped by an Uber driver, all ride-hailing apps proactively offered a panoply of features on their app to support and promote women’s safety during the ride, such as an SOS button, background verification of drivers as well as more information about the driver.

The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the need to examine the relationship between the institutional and the everyday. It created new infrastructural and logistical realities and affected the employment landscape globally. Since early 2020, app-based ordering and food delivery and supply have become ‘essential’ services. Additionally, given the digital surveillance infrastructure that platform companies had already instituted over the years in order to satisfy regulatory demands, gig platforms have become even more entrenched and normalized in urban India during a period of exceptional crisis. For instance, gig workers, including Uber and Ola drivers as well as food-delivery personnel, have been classified as ‘essential workers’, allowing them freedom of movement and work. But to maintain their ability to work, food-delivery workers have had to submit to intense scrutiny and granular surveillance. When users order food in urban India during the pandemic, Zomato’s app interface displays not only the estimated arrival time and the name of the delivery worker but also the body temperature of the worker as well as the restaurant staff and the time that the temperatures were taken. It is useful to reflect on these subtle new feature changes and functionality added to the app, which show that the normal and normative are constantly constructed and reconstructed over time. These are new norms that constitute the ‘new normal’ of platform interactions after the pandemic ends. Fuzzy questions about the coexistence of community-building and competition among workers and the social and economic support of customers are understudied in the existing analytical and empirical platform labour scholarship.

6 A Moral Economy Lens

The original concept of a ‘moral economy’ was coined and popularized by the British historian E.P. Thompson to understand the struggles of the English working class. In his analysis of the food riots in eighteenth-century England, Thompson argued that peasants and others rioted not only because of physical hunger (material causes) but also because they were outraged at the perceived immorality of the new economic system and the elites (Thompson 1971). The concept has since been developed by sociologist James C. Scott (1977, 2008) to understand successful and failed instances of social mobilization and resistance in developing countries and rural economies. Broadly, the moral economy framework argues that economic transactions operate within a moral economy that consists of social norms, obligations, shared understanding, and social contracts that undergird, sustain, and inform certain kinds of economic exchanges, decisions, and policies.

Palomera and Vetta (2016) argue that the term ‘moral economy’ can be used more broadly because the realms of material production are not distinct from those of value creation in the contemporary context of neoliberal capitalism and ‘flexible’ work. The concept has since been expanded to analyze not only rural or developing economies but, as Didier Fassin notes (2009), a rich body of studies that apply it to other things or concepts (e.g., riots, protests, government). Srinivasan and Oreglia (2020) state that, although moral economies are not static, they are deep rooted and ‘any change in the values and priorities they espouse is gradual’. Crucially, they believe that studying how moral economies work can help us understand the prioritization of specific goals and procedures in any economic system (Sayer 2000; Srinivasan & Oreglia 2020).

Anthropologist Susana Narkotzky’s (2015) ethnographic work with farming households in rural Spain examines overlap in the values of care and profit, which are essential for the production of surplus value in agriculture and garment manufacturing. This overlap is essential for the creation of surplus value because the labour force’s alienation rests on its non-alienation from the value regimes. Therefore, household and market morality have no clear distinction. A moral economy approach enables a consideration of questions of political economy such as class, capital, and state without disregarding particular values, meanings and practices (Palomera & Vetta 2016), thus making it conducive to our analysis as well as we look at economic, cultural, and moral practices in tandem.

The moral economy approach offers a departure from established ways of talking about gig economy platforms in at least two important ways. First, it enables economic questions of work to be seen as enmeshed with social questions. Second, a moral economy lens allows us to identify ‘motivations’, which is a key analytic in gig economy discussions. In various discussions on why people take up gig work globally, in addition to viewing gig work as symptomatic of a larger shift to casual work, scholars and others have also sought to document the motivations for gig work, leading them to discover, for instance, that new migrants and others seeking a steppingstone into urban labour markets accept gig work because of its low skill threshold. Others have argued that because gig workers do not identify themselves as such (but, rather, as students, entrepreneurs, as being in the process of reskilling), their motivation for mobilization and resistance is low. In all these cases, motivations mostly mean economic and rational reason for why people take up and continue doing gig work.

Set against a largely informal economic landscape, a growing youth unemployment crisis, and the low dignity of labour for non – white-collar workers, it is hardly surprising that many migrants to urban centres choose forms of gig work. Based on their ethnographic work with gym trainers and baristas in coffee shops, anthropologists Baas and Cayla (2020) suggest that ‘new services’ are sites of learning and transformation for workers through interclass interactions with customers. These new interactions, unlike other kinds of service work, enable new feelings of respect through the recognition and visibility of workers. But we believe that what is more interesting is how people yoke the template of gig work to existing norms, obligations, and values that govern urban social and economic exchanges. In our findings, we discuss the logics, understanding, and values that are normative among customers, police personnel, and other workers and the appeal to them to become gig workers in order to achieve the results they desire – whether to obtain extra time to deliver service, consideration and kindness, or to justify their so-called errant behaviours. Platform-mediated work also connects workers, customers, and platforms in new ways.

In the next section, we ask how the different stakeholders of gig platforms perceive and make sense of each other. How, if at all, have gig platforms changed the scripts of urban sociality? Do gig workers and gig consumers ponder the ethics of participating in gig platforms? How do they develop and disseminate acceptable (and possibly dynamic) responses and behaviours in the gig economy? Relatedly, what quotidian notions of justice, fairness, respect, honour, gratitude, and other values do people develop based on platform participation? What role do these values perform in making platforms work?

7 Moral Norms in Platforms

The Zomato incident described at the beginning of the article was the latest in a series of episodes on platform living that have rekindled discussions about how to imagine and define a quotidian sense of justice, fairness, merit, and good conduct in the post-platform society. As also discussed at the beginning, online and offline responses to the incident (in which a food-delivery worker was caught eating a delivery order) were far from uniform; many initially denounced such conduct as inexcusable and unhygienic, but, as the discourse continued, some also said that the event was only natural and inevitable given the conditions of food-delivery work and the enduring poor treatment of workers by platform companies and customers alike. The incident and the responses offer us a window into the ambivalence about social norms in and after platforms as well as the fact that, as people make sense of platformization through folk knowledge and theories on opaque algorithmic management, the normative grounds for behaviour on platforms also shift. In this section, we offer a typology of some key enactments of morality in daily gig economy exchanges.

7.1 ‘Please Be Kind’: Gratitude and Kindness in Platform Exchanges

Many papers have been written on the economy of gratitude globally and the role and value of gratitude in economic life in different communities and settings, but it has not yet been discussed in the context of gig work. Gratitude or being grateful is manifested in daily platform exchanges at both the customers’ and workers’ end. Scholars have rightly noted that in informal and domestic work, sociality, being indebted, and literally incurring debt with a patron, and hence relying on the patron’s mercy, and in a relationship of long-term indebtedness and gratitude reifies caste and gender hierarchies as well as services and maintains social ties that might extend actual or perceived security to workers.

Gig work is a novel category but employs social exchanges and norms seen in other forms of work, such as restaurant work, driving, and customer service. In neoliberal urban India, where many platform consumers have come to regularly depend on gig platforms to fulfil their daily needs (going to work and returning home, eating and grooming), boycotting those platforms because of their practices is simply not seen as a practical option. In our extended field work, through interviews and surveys, we found that, as platform consumers grew more and more aware of their complicity in platforms’ exploitative practices, ‘tipping’ emerged as a moral solution, a middle way between boycotting and carrying on using the platform as before.

7.2 Tipping and ‘Genuine Customers’

Tipping is not part of the normative service culture in India, and restaurant customers in India usually tip only when they experience exceptional service. Because of the emergence of platforms and the newfound intimacy and knowledge of platform workers’ conditions, especially on food-delivery platforms, tipping gained traction as a ‘good thing’, as a moral and interpersonal response, rather than a personal political stance. A majority of the respondents to a short survey of platform consumers that we conducted across India claimed that they tipped their workers on a regular basis. Interestingly, the tip amount considered appropriate was equivalent to the change that customers were owed from transactions.

The proliferation and entrenchment of gig platforms has certainly shifted social, cultural, and moral norms in urban India. In the early years of gig platform operations, when asked why platforms did not offer an option to tip workers, platform representatives (policy and product managers interviewed by the first author) explained that tipping was not a norm in India, and because platforms were primarily designed to cater to their consumers, incorporating tipping within their ‘order workflow’ might upset consumers. Since then, both food-delivery and ride-hailing platforms have recognized and incorporated tipping options; and Zomato, the food-delivery platform, has constructed a pro-social narrative around it. After a payment is made, the platform conveys ‘a message of thanks’ to the consumer on behalf of the worker. On Uber, in an earlier version of the platform, while a passenger waited for a driver to arrive, the platform would display a small profile card with the driver’s name and details and what the driver was saving up for or working towards.

Ways in which customers expressed themselves as empathetic subjects other than tipping were by offering water, food, and shelter during a rain storm and by providing financial help to workers in need. Similar to asking for the internet publics to forgive the errant Zomato worker (who might have eaten from his delivery), many jumped into online conversations about the quality of service or unpleasant experiences with Uber drivers and remind others that they were in fact dealing with severely overworked and underpaid workers, asking them to be understanding and kind. On posts in which customers complained about the food being cold or the wrong order being delivered or the driver not speaking the customer’s language, again many concerned customers jumped in and tried to offer a different perspective on the incident.

Another interesting avenue of customer support was opened when workers had the opportunity to deliver food to a public figure. Some bold workers shared their grievances with reality television and online celebrities such as Eijaz Khan and Rakhi Sawant.4 Among workers kind customers were referred to as ‘genuine customers’. Genuineness was approximated by workers based on calculations involving the geographic area from which the order was placed, the value of the order, and the time of the day. As workers explained, customers who are not genuine might request additional items such as cigarettes, alcohol, and condoms; refuse to pay if it is a cash on delivery order; or might generally not cooperate with workers. Further, rather than being constant, the lack of genuineness was heightened at night because, for instance, it was more common for customers to misbehave (be verbally abusive, refuse to pay) or be in a drunken stupor at that time of day.

7.3 Polite Professionalism and Extraordinary Acts of Kindness

In platform work, kindness by customers is also calibrated in response to workers’ polite professionalism. Platform exchanges build on the emotional labour of workers. Predictably, workers receive training to refer to customers as ‘sir’ or ‘madam’ and show respect through their appearance. Several platforms sell uniforms (t-shirts with the company brand) to workers and ensure maintenance of grooming standards, which generally recommend full pants (not ripped), closed shoes, and no ‘funky’ or unconventional (blue, pink, blonde) hair colour. Food-delivery platform companies engage auditors who perform random checks to ensure that workers are adhering to these standards.

Along with these prescriptions of politeness, platform companies also anticipate working-class resentment among workers. The second author found that platform offices do not entertain restaurant and driver partners in the same space. Food-delivery workers who joined Zomato when it started recounted that Zomato had entertained all partners in one office but, after repeated strikes and gatherings by workers, they separated delivery and restaurant partner offices. Similarly, as the first author discovered as well, using one instance of a strike by ride-hailing drivers that turned violent as an excuse, Uber instituted granular video surveillance, doing patdowns, bag checks, and even electronic device registration at its biggest global ‘greenlight centre’ in Bengaluru5 – the hub that drivers visit to resolve disputes or technical issues with the app. In both cases, politeness as intrinsic to a larger performance of professionalism and politeness as a non-negotiable quality is often pegged to concerns about gendered safety and is a key moral threshold through which platforms demand and control compliant behaviour from male gig workers. Sneha Annavarapu (2021), in work reflecting on the threat perception among female passengers and their cab drivers, has written about the mutual suspicion and pathologization of working-class men and their affluent others (female customers). We echo this observation to further determine why our informants’ performance of politeness and professionalization was expected and instituted by companies even in the absence of their interaction with an actual customer or female employee or worker.

Slowly but steadily, platform culture as an urban culture has also come to signify and be sustained by tropes of quotidian kindness. Every so often, a story about a kind or responsible driver or food-delivery worker surfaces and goes viral on social media forums. These stories invoke the ‘daily heroes’ trope to celebrate drivers who go above and beyond their role and return a passenger’s purse, phone, or expensive goods, help a sick customer, or travel far in the rain or other inclement weather to deliver service. During the COVID-19 pandemic, platform stories about a driver transporting old and sick patients went viral, too. A less recurrent story/trope is that of the elusive female driver or delivery worker, which has a different ending: some customers are very grateful for the female worker’s efforts and admire her bravery in doing this work, and some go further and frame this episode as a sign of women’s empowerment in India. At the same time, in the light of multiple rape incidents involving Uber vehicles and instances of misconduct by food-delivery workers, platform workers also have to battle negative stereotypes about their hygiene, professionalism, and conduct, especially towards women. Insignia on cabs includes the slogan ‘this cab respects women’.

8 Dynamic Morality in Platform Work

In this section of the paper, we discuss moral orientations in daily platform work. We emphasize dynamism (as opposed to stability) as a key characteristic of moral responses and reasoning within quotidian work to highlight the shifting politics created by daily uncertainty under neoliberalism. We also to refer to a morality that directly responds to the algorithmic uncertainty created by ‘dynamic surge pricing’ used by gig platforms. As we observed, moral stances on cheating (the platform or the consumer) and dishonesty were seldom fixed or resolved among gig workers. Much like the fast-changing algorithmic outputs that gig apps produce through computational considerations (or data points) of daily reality, supply, demand, and so forth, workers’ feelings and moral reasoning on being ethical depended on their assessment of the platform at the time.