These 5 cancers are more common, claiming millions of lives every year. On World Cancer Day, the most common cancers globally, causing millions of deaths, are breast, lung, colorectal (colon and rectum), and prostate cancers, with liver cancer also high on the mortality list, though many cases are preventable through lifestyle changes and early detection, highlighting the need for equitable access to care.

Key facts

- Cancer is a leading cause of death worldwide, accounting for nearly 10 million deaths in 2020, or nearly one in six deaths.

- The most common cancers are breast, lung, colon and rectum and prostate cancers.

- Around one-third of deaths from cancer are due to tobacco use, high body mass index, alcohol consumption, low fruit and vegetable intake, and lack of physical activity. In addition, air pollution is an important risk factor for lung cancer.

- Cancer-causing infections, such as human papillomavirus (HPV) and hepatitis, are responsible for approximately 30% of cancer cases in low- and lower-middle-income countries.

- Many cancers can be cured if detected early and treated effectively.

Overview

Cancer is a generic term for a large group of diseases that can affect any part of the body. Other terms used are malignant tumours and neoplasms. One defining feature of cancer is the rapid creation of abnormal cells that grow beyond their usual boundaries, and which can then invade adjoining parts of the body and spread to other organs; the latter process is referred to as metastasis. Widespread metastases are the primary cause of death from cancer.

The problem

Cancer is a leading cause of death worldwide, accounting for nearly 10 million deaths in 2020 (1). The most common in 2020 (in terms of new cases of cancer) were:

- breast (2.26 million cases);

- lung (2.21 million cases);

- colon and rectum (1.93 million cases);

- prostate (1.41 million cases);

- skin (non-melanoma) (1.20 million cases); and

- stomach (1.09 million cases).

The most common causes of cancer death in 2020 were:

- lung (1.80 million deaths);

- colon and rectum (916 000 deaths);

- liver (830 000 deaths);

- stomach (769 000 deaths); and

- breast (685 000 deaths).

Each year, approximately 400 000 children develop cancer. The most common cancers vary between countries. Cervical cancer is the most common in 23 countries.

Causes

Cancer arises from the transformation of normal cells into tumour cells in a multi-stage process that generally progresses from a pre-cancerous lesion to a malignant tumour. These changes are the result of the interaction between a person’s genetic factors and three categories of external agents, including:

- physical carcinogens, such as ultraviolet and ionizing radiation;

- chemical carcinogens, such as asbestos, components of tobacco smoke, alcohol, aflatoxin (a food contaminant), and arsenic (a drinking water contaminant); and

- biological carcinogens, such as infections from certain viruses, bacteria, or parasites.

WHO, through its cancer research agency, the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), maintains a classification of cancer-causing agents.

The incidence of cancer rises dramatically with age, most likely due to a build-up of risks for specific cancers that increase with age. The overall risk accumulation is combined with the tendency for cellular repair mechanisms to be less effective as a person grows older.

Risk factors

Tobacco use, alcohol consumption, unhealthy diet, physical inactivity and air pollution are risk factors for cancer and other noncommunicable diseases.

Some chronic infections are risk factors for cancer; this is a particular issue in low- and middle-income countries. Approximately 13% of cancers diagnosed in 2018 globally were attributed to carcinogenic infections, including Helicobacter pylori, human papillomavirus (HPV), hepatitis B virus, hepatitis C virus, and Epstein-Barr virus (2).

Hepatitis B and C viruses and some types of HPV increase the risk for liver and cervical cancer, respectively. Infection with HIV increases the risk of developing cervical cancer six-fold and substantially increases the risk of developing select other cancers such as Kaposi sarcoma.

Reducing the burden

Between 30 and 50% of cancers can currently be prevented by avoiding risk factors and implementing existing evidence-based prevention strategies. The cancer burden can also be reduced through early detection of cancer and appropriate treatment and care of patients who develop cancer. Many cancers have a high chance of cure if diagnosed early and treated appropriately.

Prevention

Cancer risk can be reduced by:

- not using tobacco;

- maintaining a healthy body weight;

- eating a healthy diet, including fruit and vegetables;

- doing physical activity on a regular basis;

- avoiding or reducing consumption of alcohol;

- getting vaccinated against HPV and hepatitis B if you belong to a group for which vaccination is recommended;

- avoiding ultraviolet radiation exposure (which primarily results from exposure to the sun and artificial tanning devices) and/or using sun protection measures;

- ensuring safe and appropriate use of radiation in health care (for diagnostic and therapeutic purposes);

- minimizing occupational exposure to ionizing radiation; and

- reducing exposure to outdoor air pollution and indoor air pollution, including radon (a radioactive gas produced from the natural decay of uranium, which can accumulate in buildings — homes, schools and workplaces).

Early detection

Cancer mortality is reduced when cases are detected and treated early. There are two components of early detection: early diagnosis and screening.

Early diagnosis

When identified early, cancer is more likely to respond to treatment and can result in a greater probability of survival with less morbidity, as well as less expensive treatment. Significant improvements can be made in the lives of cancer patients by detecting cancer early and avoiding delays in care.

Early diagnosis consists of three components:

- being aware of the symptoms of different forms of cancer and of the importance of seeking medical advice when abnormal findings are observed;

- access to clinical evaluation and diagnostic services; and

- timely referral to treatment services.

Early diagnosis of symptomatic cancers is relevant in all settings and the majority of cancers. Cancer programmes should be designed to reduce delays in, and barriers to, diagnosis, treatment and supportive care.

Screening

Screening aims to identify individuals with findings suggestive of a specific cancer or pre-cancer before they have developed symptoms. When abnormalities are identified during screening, further tests to establish a definitive diagnosis should follow, as should referral for treatment if cancer is proven to be present.

Screening programmes are effective for some but not all cancer types and in general are far more complex and resource-intensive than early diagnosis as they require special equipment and dedicated personnel. Even when screening programmes are established, early diagnosis programmes are still necessary to identify those cancer cases occurring in people who do not meet the age or risk factor criteria for screening.

Patient selection for screening programmes is based on age and risk factors to avoid excessive false positive studies. Examples of screening methods are:

- HPV test (including HPV DNA and mRNA test), as preferred modality for cervical cancer screening; and

- mammography screening for breast cancer for women aged 50–69 residing in settings with strong or relatively strong health systems.

Quality assurance is required for both screening and early diagnosis programmes.

Treatment

A correct cancer diagnosis is essential for appropriate and effective treatment because every cancer type requires a specific treatment regimen. Treatment usually includes surgery, radiotherapy, and/or systemic therapy (chemotherapy, hormonal treatments, targeted biological therapies). Proper selection of a treatment regimen takes into consideration both the cancer and the individual being treated. Completion of the treatment protocol in a defined period of time is important to achieve the predicted therapeutic result.

Determining the goals of treatment is an important first step. The primary goal is generally to cure cancer or to considerably prolong life. Improving the patient’s quality of life is also an important goal. This can be achieved by support for the patient’s physical, psychosocial and spiritual well-being and palliative care in terminal stages of cancer.

Some of the most common cancer types, such as breast cancer, cervical cancer, oral cancer, and colorectal cancer, have high cure probabilities when detected early and treated according to best practices.

Some cancer types, such as testicular seminoma and different types of leukaemia and lymphoma in children, also have high cure rates if appropriate treatment is provided, even when cancerous cells are present in other areas of the body.

There is, however, a significant variation in treatment availability between countries of different income levels; comprehensive treatment is reportedly available in more than 90% of high-income countries but less than 15% of low-income countries (3).

Palliative care

Palliative care is treatment to relieve, rather than cure, symptoms and suffering caused by cancer and to improve the quality of life of patients and their families. Palliative care can help people live more comfortably. It is particularly needed in places with a high proportion of patients in advanced stages of cancer where there is little chance of cure.

Relief from physical, psychosocial, and spiritual problems through palliative care is possible for more than 90% of patients with advanced stages of cancer.

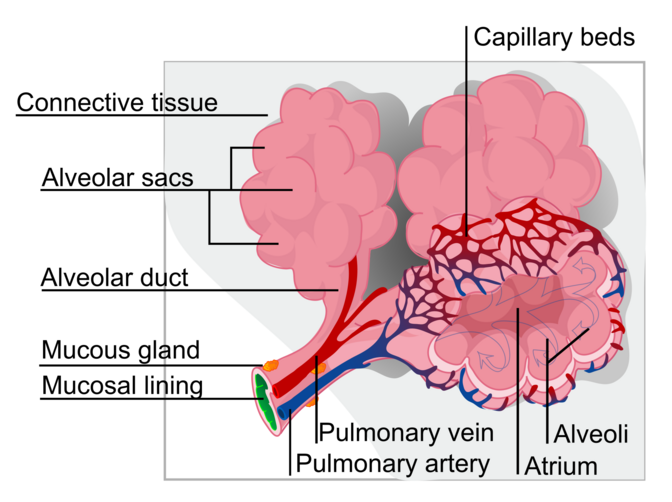

Effective public health strategies, comprising community- and home-based care, are essential to provide pain relief and palliative care for patients and their families.Improved access to oral morphine is strongly recommended for the treatment of moderate to severe cancer pain, suffered by over 80% of people with cancer in the terminal phase. Alveoli are tiny, grape-like air sacs at the end of the bronchioles in the lungs, acting as the primary site for gas exchange between the respiratory and circulatory systems. Humans have hundreds of millions of these elastic sacs, which expand during inhalation to allow oxygen to enter the blood and contract during exhalation to release carbon dioxide.

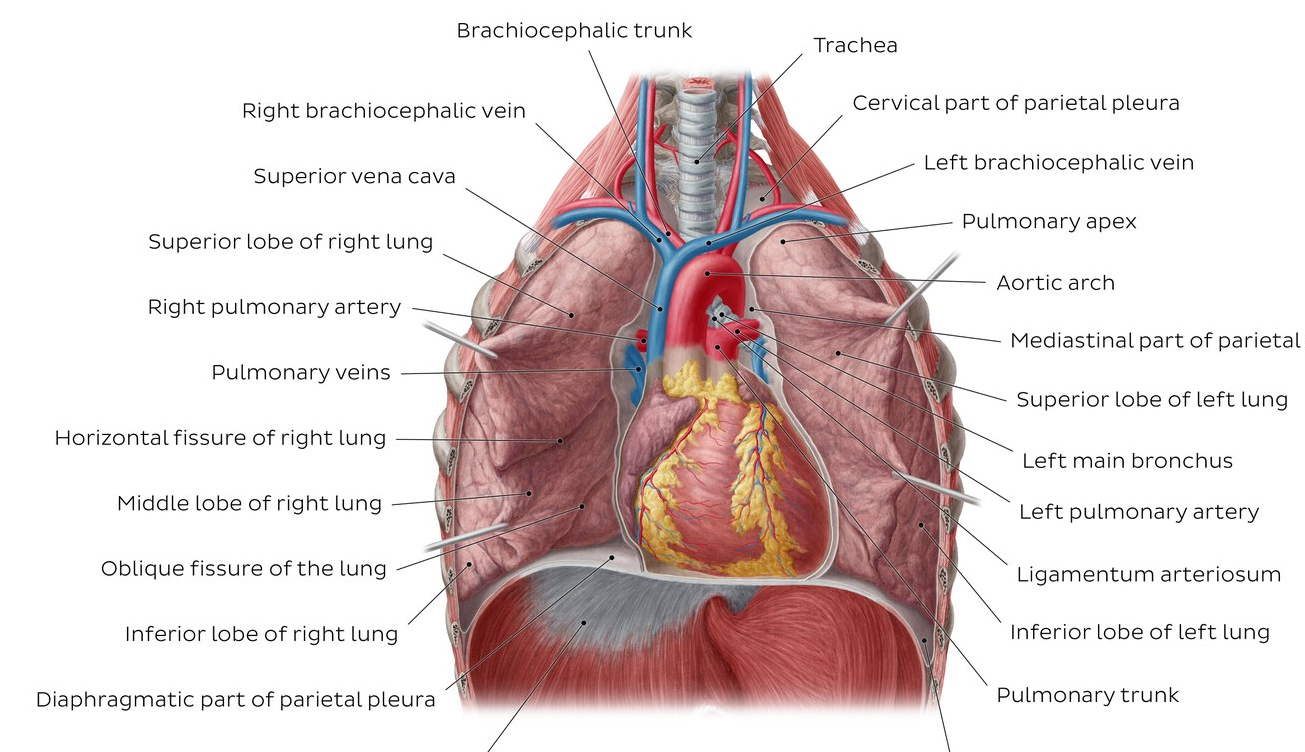

The lungs, which is the organ for respiration is a paired cone shaped organs lying in the thoracic cavity separated from each other by the heart and other structures in the mediastinum.

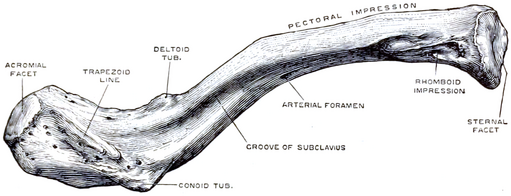

The Clavicle also known as the collar bone, is a sigmoid-shaped long bone that makes up the front part of the shoulder. It sits between the shoulder blade and the sternum. There are 2 clavicles in a person, one on the right and the other one on the left side. It is the only long bone in the body that lies horizontally.

Articulations

Due to the clavicle’s structure, there are only two planar diarthrosis articulations that can be found. This type of articulation is also known as a ‘double plane joint’ – where two joint cavities are separated by a layer of articular cartilage.

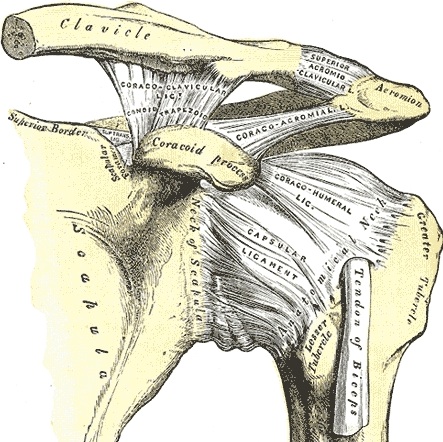

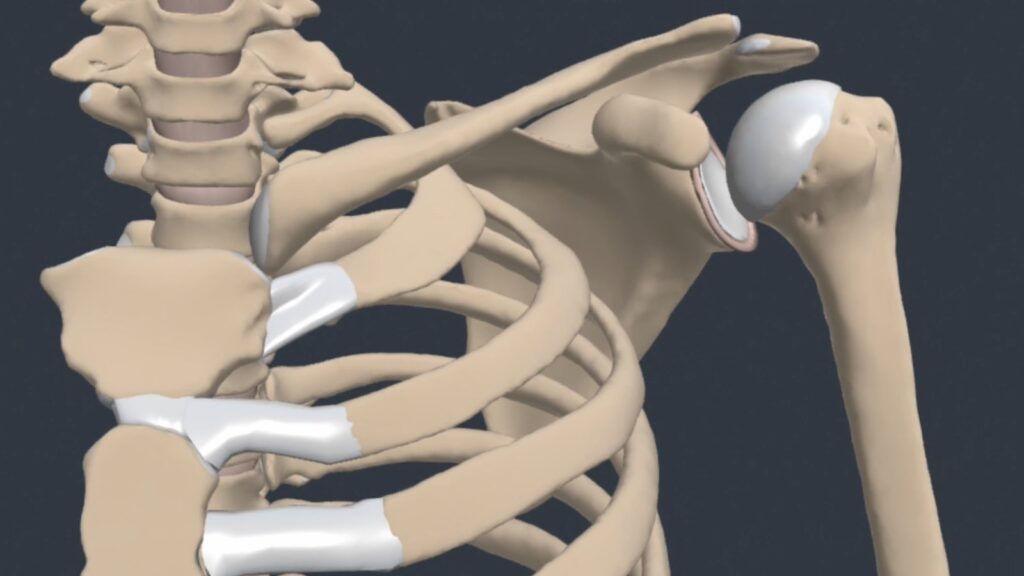

The glenohumeral (GH) joint is a true synovial ball-and-socket style, multiaxial, diarthrodial joint.

Description

The humerus is a long bone which consists of a shaft (diaphysis) and two extremities (epiphysis). It is the longest bone of the upper extremity.

Introduction

Welcome to the fascinating world of humerus anatomy—a cornerstone in the realm of physiotherapy. Understanding the intricacies of the humerus, the long bone that forms the upper arm, is paramount for physiotherapists seeking to optimise patient care and rehabilitation.

The humerus, with its unique structure comprising a head, anatomical neck, surgical neck, tuberosities, and body, plays a pivotal role in the intricate dance of the upper limb’s movements. As a physiotherapist with a keen focus on patient well-being, delving into the nuances of humerus anatomy opens up a myriad of possibilities for effective intervention and support.

Practical Applications

In the dynamic field of physiotherapy, an in-depth understanding of humerus anatomy is instrumental in tailoring interventions for optimal patient outcomes . Physiotherapists dealing with humerus-related conditions can apply this knowledge in various practical ways:

1. Tailor Rehabilitation Programs: – A nuanced understanding of the humerus allows physiotherapists to tailor rehabilitation programs to the specific needs of patients recovering from humerus-related injuries, such as fractures or dislocations .

2. Enhance Range of Motion:- Knowledge of the humerus’ articulations and muscle attachments empowers physiotherapists to design exercises that effectively enhance range of motion in the upper limb, crucial for rehabilitation post-humerus surgery or trauma .

3. Address Functional Impairments:- Physiotherapists can leverage their understanding of humerus anatomy to address functional impairments resulting from humerus-related conditions. This includes developing targeted interventions to improve activities of daily living affected by these impairments .

4. Prevent Secondary Complications:- Proactive physiotherapy, grounded in sound anatomical knowledge of the humerus, aids in the prevention of secondary complications. Physiotherapists can implement strategies to mitigate issues such as muscle imbalances or joint stiffness, enhancing overall patient well-being .

5. Facilitate Informed Patient Education:- Physiotherapists, armed with a profound understanding of humerus anatomy, can play a crucial role in patient education. By explaining the relevance of humerus anatomy in a patient-friendly manner, they foster collaboration and empower patients in their recovery journey .

These practical applications underscore the pivotal role of humerus anatomy in guiding effective physiotherapeutic interventions, promoting holistic patient care.

Upper Extremity Features

The head of the humerus is the proximal articular surface of the upper extremity, which is an irregular hemisphere. The anatomical neck is the part between the head and the tuberosities.

The surgical neck is the part between the tuberosities and the shaft.

The greater tuberosity it is located lateral to the head at the proximal end.

The lesser tuberosity is located inferior to the head, on the anterior part of the humerus, Its very prominent and palpable.

Bicipital (intertubercular) groove is located between the two tuberosities. Body Features

The body of the humerus has three borders and three surfaces.

Borders

- Anterior

- Lateral

- Medial

Surfaces

Posterior

Antero-lateral

Antero-medial

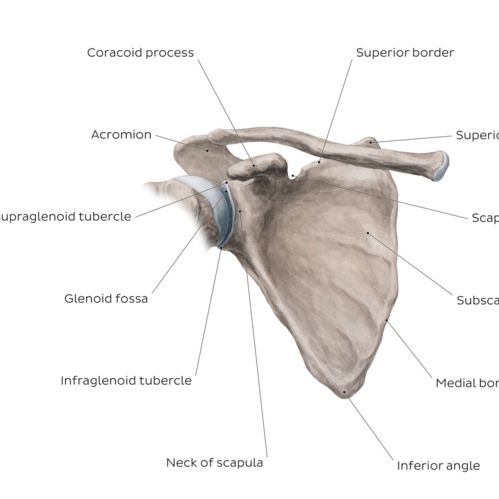

Introduction

Overview of the scapula bone – anterior view

Introduction

Bone is a specialised connective tissue that forms most of the skeleton, providing the structural foundation for the human body. Bone is a metabolically active connective tissue that constantly remodels and repairs. It is capable of restoring itself to full function after injury. To support its various roles, bone must be both rigid and stiff, and flexible and elastic. This article discusses the basic structure, development and function of bone and overviews bone pathologies.

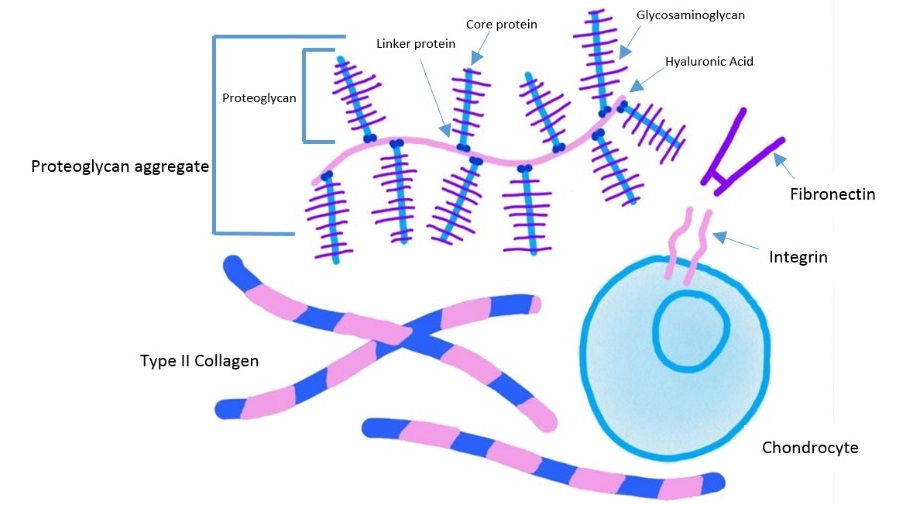

Bone Composition and Structure

connective tissues non cellular portion is known as the extracellular matrix (ECM), giving the physical scaffolding for the cells. The ECM is able to hold water, provide appropriate hydration of the tissue and form part of a selective barrier to the external environment. The ECM also initiates crucial biochemical and biomechanical cues for tissue morphogenesis, differentiation and homeostasis.

In human, the main components of the extracellular matrix are:

- Fibrous elements (e.g. elastin, reticulin),

- Link proteins (e.g. fibronectin, laminin), and

- Space filling molecules

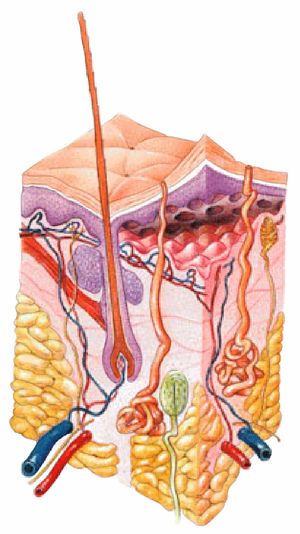

The Integumentary System

The integumentary system is the largest organ of the body that forms a physical barrier between the external environment and the internal environment that it serves to protect and maintain.

The integumentary system includes

- epidermis, dermis

- Hypodermis

- Associated

The endocrine system is a network of glands and organs located throughout the body. It’s similar to the nervous system in that it plays a vital role in controlling and regulating many of the body’s functions.

Neurotransmitters are often referred to as the body’s chemical messengers.

Overview

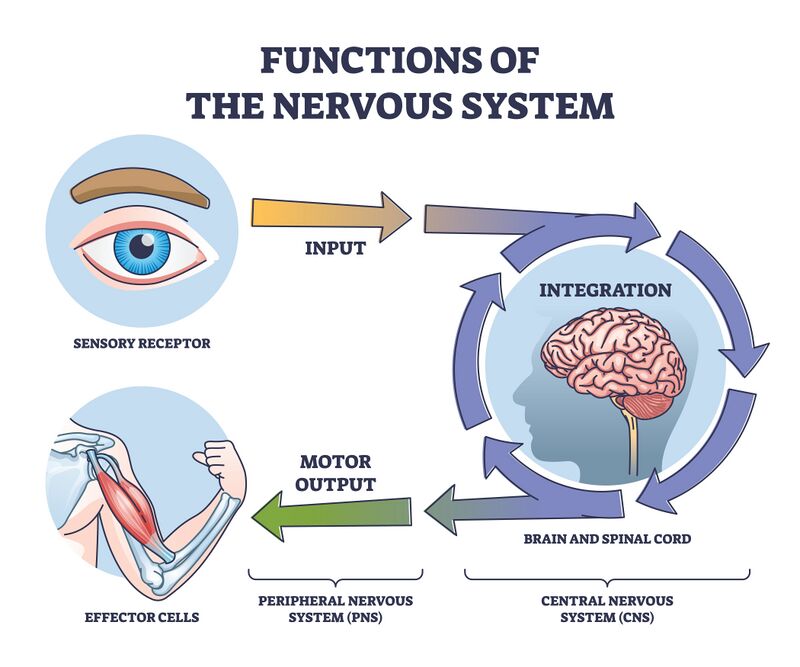

The nervous system consists of extensive neural networks. Communication between these networks facilitates thinking, language, feeling, learning, memory, motor function and sensation. Through the plasticity of our existing cells and neural stem cells, our nervous system can adapt to new situations and respond to injury.

Neuroplasticity or brain plasticity is defined as the ability of the nervous system to change its activity in response to intrinsic or extrinsic stimuli by reorganising its structure, functions, or connections.

The nervous system has three specific functions:

Introduction

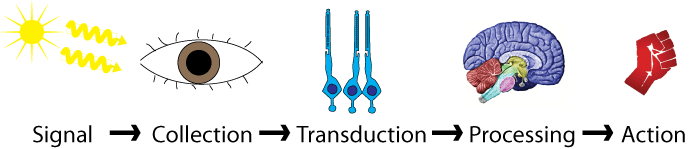

Humans can perceive various types of sensations, and with this information, our motor movement is determined. We become aware of the world by way of sensation. Sensations can also be protective to the body, by registering eg environmental cold or warm, and painful needle prick. All the daily activities carry associations with sensations.

Broadly, these sensations can classify into two categories. General Overview of Pain

The most widely accepted and current definition of pain, established by the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP), is:

“An unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with, or resembling that associated with, actual or potential tissue damage.”

Although several theoretical frameworks have been proposed to explain the physiological basis of pain, not one theory has been able to exclusively incorporate all aspects of pain perception. The four most influential theories of pain perception include Specificity, Intensity, Pattern and Gate Control theories of pain. However, in 1968, Melzack and Casey described pain as multi-dimensional, where the dimensions are not independent, but rather interactive. The dimensions include sensory-discriminative, affective-motivational and cognitive-evaluate components.

Pain Mechanisms

Determining the most plausible pain mechanism(s) is crucial during clinical assessments as this can serve as a guide to determine the most appropriate treatment(s) for a patient. Therefore, criteria upon which clinicians may base their decisions for appropriate classifications have been established through an expert consensus-derived list of clinical indicators. The information below is adapted from research by Smart et al. that classified pain mechanisms as ‘nociceptive’, ‘peripheral neuropathic’ and ‘central’ and outlined both subjective and objective clinical indicators for each. This page also introduces ‘nociplastic’ pain, which was proposed as a term in 2016.

When considering pain mechanisms, please remember Hickam’s dictum – “a patient can have multiple coincident unrelated disorders.”

- Multiple pain mechanisms, as well as psychological and social factors, may be involved at one time. Treatment should focus on the dominant mechanism, as well as any recovery limiting psychological or social factors.

- Pain mechanisms and psychological and social factors can alter and shift with time.

- Pain is based on the patient’s perception of threat. Often the threat is real and sometimes it is not. Understanding pain mechanisms will help you determine when the threat is real.

Nociceptive Pain Mechanism

Nociception is defined as:

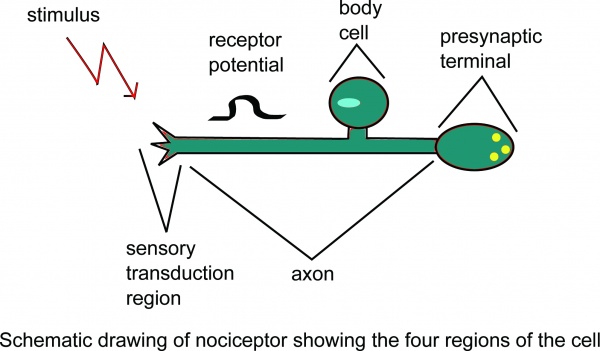

“1. Pathological process in peripheral organs and tissues. 2. Pain projection into damaged body part or referred pain.”

Nociception is a subcategory of somatosensation. Nociception is the neural processes of encoding and processing noxious stimuli. Nociception refers to a signal arriving at the central nervous system as a result of the stimulation of specialised sensory receptors in the peripheral nervous system called nociceptors. Nociceptors are activated by potentially noxious stimuli; as such nociception is the physiological process by which body tissues are protected from damage. Nociception is important for the “fight or flight response” of the body and protects us from harm in our surrounding environment.

Schematic drawing of nociceptor showing the four regions of the cell.

Nociceptors can be activated by three types of stimulus within the target tissue – thermal (temperature), mechanical (e.g stretch/strain) and chemical (e.g. pH change as a result of local inflammatory process). Thus, a noxious stimulus can be categorised into one of these three groups. Nociceptive pain is associated with the activation of peripheral receptive terminals of primary afferent neurons in response to noxious chemical (inflammatory), mechanical or ischaemic stimuli.

Introduction

When we think of pain behaviours, we tend to think of our behaviour to pain but the type of pain and how they present is also an important factor in understanding pain. Human pain behaviours are much more than a sensory perception of tissue injury. Pain is a complex and unpleasant multi-dimensional experience of the self associated with perceived tissue threat.

Pain behaviours can be adaptive or pathogenic, as when the pain behaviour is excessive in comparison to the objective pathology. It has been found that when pain behaviour exists in pain patients, a psychiatric disease may aggravate pain.

Pain types differ. There are 4 widely accepted pain types relevant for musculoskeletal pain: Nociception is a subcategory of somatosensation. Nociception is the neural processes of encoding and processing noxious stimuli. Nociception refers to a signal arriving at the central nervous system as a result of the stimulation of specialised sensory receptors in the peripheral nervous system called nociceptors. A ”’noxious stimulus”’ is a strong enough to threaten the body’s integrity. Noxious stimulation induces peripheral [[Afferent signal|afferents]] responsible for [[Transduction (physiology)|transducing]] pain including [[A delta fiber|A-delta]] and [[Group C nerve fiber|C-]] nerve fibers, as well as [[Free nerve ending|free nerve endings]]) throughout nervous system of an organism.

The ability to perceive noxious stimuli is a prerequisite for [[nociception]], which itself is a prerequisite for [[Pain Nociceptive|nociceptive pain]]. These include [[Reflex|reflexive]], [[Escape response|escape behaviors]], to avoid harm to an organism’s body.

Because of rare genetic conditions that inhibit the ability to perceive physical pain, such as noxious stimulation does not invariably lead to tissue damage. Noxious stimuli can either be [[Mechanics|mechanical]] (e.g. pinch (action)|pinching or other tissue deformation (engineering)|deformation), chemical (e.g. exposure to acid or irritation|irritant), or Heat|thermal (e.g. high or low temperatures).

There are some types of tissue damage that are not detected by any sensory receptors, and thus cannot cause pain. Therefore, not all noxious stimuli are adequate stimuli of nociceptors. The adequate stimuli of nociceptors are termed ”nociceptive stimuli”.

Introduction

Neurogenic inflammation is the physiological process by which mediators are released directly from the cutaneous nerves to initiate an inflammatory reaction. This results in production of local inflammatory responses including erythema, swelling, temperature increase, tenderness, and pain. Fine unmyelinated afferent somatic C-fibers, which respond to low intensity mechanical and chemical stimulations, are largely responsible for the release of inflammatory mediators. When stimulated, these nerve fibers in the cutaneous nerves release active neuropeptides – substance P and calcitonin gene related peptide (CGRP) – rapidly into the microenvironment, triggering a series of inflammatory responses. Although neurogenic inflammation and immunologic inflammation can exist at the same time, the two are not clinically identical. There is an important distinction from immunogenic inflammation, which is the very first protective and reparative response generated by the immune system when a pathogens enters a body while neurogenic inflammation involves a direct relationship betwen the nervous system and the inflamatory reactions. Although neurogenic inflammation and immunologic inflammation can exist concurrently, the two are not clinically identical.

Mechanism

In order to fully appreciate the involvement of neurogenic inflammation in various clinical conditions, it is important to understand its mechanisms of action. To date, two possible mechanisms of neurogenic inflammation – backfiring and neurogenic switching – have been proposed.

Under normal circumstances, peripheral tissue damage in the body will cause sensory neurones to send an impulse via the dorsal root ganglion into the central nervous system (CNS) for further processing. In some cases, however, instead of the impulse being transmitted centrally, it may shoot down the axon directly, causing neuropeptide release at the distal end of the neurone. This phenomenon is known as backfiring and was introduced as a mechanism for neurogenic inflammation by Butler and Moseley (2003). Consequently, the release of neuropeptides by the irritated neurone induces inflammation in the distal tissues. Sustained inflammation was also suggested to be caused by persistent backfiring.

Another proposed mechanism is known as neurogenic switching. Under this mechanism, the sensory impulse generated locally gets normally transmitted from the site of activation to the CNS, which then creates an efferent signal to regulate the inflammation. However, the signal is rerouted via the CNS to a distant location and produces neurogenic inflammation at the second location. In fact, neurogenic switching was further illustrated using the multiple chemical sensitivity syndromes, in which detection of chemical irritants by the respiratory system triggers inflammatory responses in various secondary organ systems. Similarly, this neuronal pathway can be a possible explanation.

Clinical Examples

Clinically, involvement of neurogenic inflammation has been recognized in a number of inflammatory disorders. Neurogenic inflammation has also been implicated in the pathophysiology of numerous diseases, including complex regional pain syndrome, migraine, and irritable bowel and bladder syndromes. However,in the setting of wound healing, neurogenic inflammation helps maintain tissue integrity and facilitate tissue repair.

Introduction

Complex Regional Pain Syndrome (CRPS) is defined as: “a syndrome characterized by a continuing (spontaneous and/or evoked) regional pain that is seemingly disproportionate in time or degree to the usual course of any known trauma or other lesion.”

CRPS predominantly affects the distal parts of an extremity. Characteristic features include allodynia (pain from typically non-painful stimuli) and hyperalgesia (exaggerated pain response), as well as sudomotor, vasomotor, and trophic changes (e.g. pitting of the nails, increased or decreased hair growth in the area, and changes in the skin tone).

The pathophysiology of CRPS is not fully understood, but it is believed to be a multifactorial process affecting both the peripheral and central nervous systems. Various mechanisms have been identified in CRPS, including inflammation, peripheral and central sensitisation, brain plasticity, genetic factors, psychologic factors, and more. It’s not yet clear how these factors interact.

CRPS has had a number of names, including reflex sympathetic dystrophy, causalgia, algodystrophy, Sudeck’s atrophy, neurodystrophy and post-traumatic dystrophy. To standardise the nomenclature, the name “complex regional pain syndrome” was adopted in 1995 by the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP).

Classification and Phenotypes

Different classifications and types of CRPS have been proposed and are continuing to evolve. Further research is needed to refine classification systems and identify clinically meaningful subgroups that guide targeted interventions. This section discusses some of the classifications and subtypes you might see described in the literature.

CRPS is most commonly subdivided into two subtypes: type I and type II. In type I CRPS, patients have no identified major nerve lesion. This is the more common subtype. Type II occurs after major nerve damage. However, there is a large overlap in clinical features between subtypes. There is also evidence of nerve injury in type 1. Thus, these subtypes may have limited clinical significance.

Historically, CRPS was described as having three progressive phases. Stage I refers to the acute period, and lasts up to 3 months. Stage II is the dystrophic stage and occurs 3 to 6 months after onset. Stage III is the atrophic stage and occurs after 6 months. However, these stages have also been questioned and aren’t substantiated in current research.

More recently, two different subtypes have been suggested: warm CRPS and cold CRPS. Warm CRPS is a more inflammatory phenotype, where the individual presents with a warm, red, oedematous, sweaty extremity. Conversely, cold CRPS is considered a central phenotype. It is associated with colder temperatures, blue / pale skin, and less oedema. Warm and cold CRPS tend to cause similar levels of pain, but warm CRPS tends to be of shorter duration than cold CRPS. A warm presentation is the most common in early CRPS.

Dimova et al. have recently proposed a classification for CRPS based on neurological examination findings. They propose three phenotypes: (1) a central phenotype, with motor signs, allodynia, and glove/stocking-like sensory deficits; (2) a peripheral inflammation phenotype, with oedema, changes in skin colour and temperature, sweating, and trophic changes; and (3) a mixed presentation, with overlapping features of both phenotypes.

Epidemiology

Incidence and Prevalence

CRPS incidence appears to vary according to global location. For example, studies show that Minnesota has an incidence of 5.46 per 100,000 person-years for CRPS type I and 0.82 per 100,000 person-years for CRPS type II, whilst the Netherlands in 2006 had 26.2 cases per 100,000 person-years. Research shows that CRPS is more common in females than males, with a ratio of 3.5:1. CRPS can affect people of all ages, including children as young as three years old and adults as old as 75 years, but typically is most prevalent in the mid-thirties. CRPS Type I occurs in 5% of all traumatic injuries, with 91% of all CRPS cases occurring after surgery.

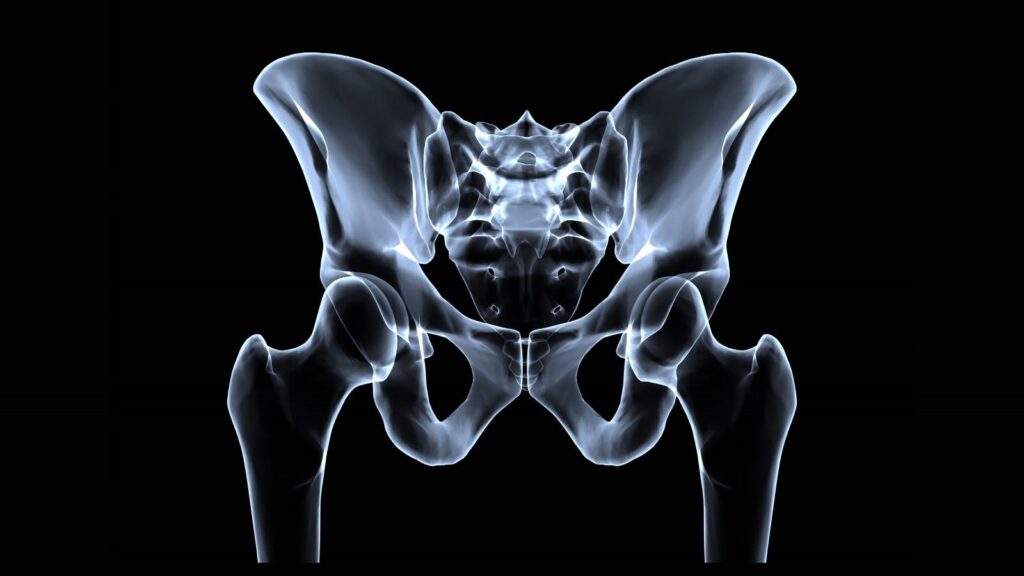

Location

The location of CRPS varies from person to person, mostly affecting the extremities, occurring slightly more in the lower extremities (+/- 60%) than in the upper extremities (+/- 40%). It can also appear unilaterally or bilaterally.

Prognosis

Approximately 15% of early CRPS (up to 6-18 months duration) fail to recover and early onset of cold CRPS predicts poor recovery.

Aetiology

Complex regional pain syndrome can develop after the occurrence of different types of injuries, such as:

- Minor soft tissue trauma (sprains)

- Surgeries

A fracture is a “complete or incomplete break in the anatomic continuity of bone, which leads to mechanical instability of the bone.”

The clinical features of fracture include pain, tenderness, bruising, swelling and sometimes deformity / movement restriction. Fractures tend to occur alongside other injuries, such as soft tissue, vascular or nerve injuries.

Fractures have different causes. Traumatic fractures occur when healthy bone is exposed to an overwhelming force (e.g. a fall or car accident). Repetitive sub-maximal loading fractures are often seen in running or jumping sports where there is a history of overload (i.e. stress fractures). Pathological fractures may occur in bones weakened by focal lesions (e.g. malignancy). Finally, specific bone conditions can lead to decreased bone density or softness of the bone especially following immobilisation

- Contusions

- Crush injuries

- Nerve lesions

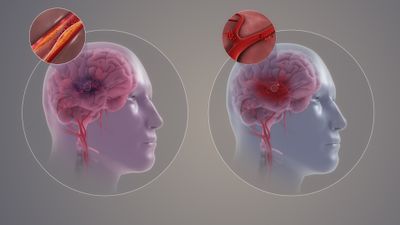

According to the World Health Organisation, a Stroke is defined as an accident to the brain with “rapidly developing clinical signs of focal or global disturbance to cerebral function, with symptoms lasting 24 hours or longer, or leading to death, with no apparent cause other than of vascular origin and includes cerebral infarction, intracerebral hemorrhage, and subarachnoid hemorrhage”.

Acute stroke is also commonly called a cerebrovascular accident which is not a term preferred by most stroke neurologists. Stroke is NOT an accident. The better and more meaningful term is “brain attack”, similar in significance to “heart attack”.

There are two main types of strokes.

- The commoner type is an ischemic stroke, caused by interruption of blood flow to a certain area of the brain. Ischemic stroke accounts for 85% of all acute strokes. According to the TOAST classification, there are four main types of ischemic strokes. These are large vessel atherosclerosis, small vessel diseases

A fracture is a “complete or incomplete break in the anatomic continuity of bone, which leads to mechanical instability of the bone.”

The clinical features of fracture include pain, tenderness, bruising, swelling and sometimes deformity / movement restriction. Fractures tend to occur alongside other injuries, such as soft tissue, vascular or nerve injuries.

Fractures have different causes. Traumatic fractures occur when healthy bone is exposed to an overwhelming force (e.g. a fall or car accident). Repetitive sub-maximal loading fractures are often seen in running or jumping sports where there is a history of overload (i.e. stress fractures). Pathological fractures may occur in bones weakened by focal lesions (e.g.malignancy). Finally, specific bone conditions can lead to decreased bone density or softness of the bone especially following immobilisation, cardio embolism strokes and cryptogenic strokes (see left hand picture on image).

15% of acute strokes are hemorrhagic strokes which are caused by bursting of a blood vessel i.e. acute hemorrhage.